You are here

Camels emerge from the dusts of oblivion

08.23.2020, by

Three years ago, in a virtually unexplored part of northern Saudi Arabia, exceptional animal sculptures depicting life-sized camelids and equids were discovered. Were they carved by the Nabateans some 2,000 years ago? New fieldwork at what is now called the “Camel Site” revealed much earlier origins. Follow the researchers on their 2019 expedition.

Guillaume Charloux is an archaeologist at laboratoire Orient et Méditerranée (CNRS/Université Panthéon-Sorbonne/Sorbonne Université/Collège de France/ École pratique des hautes études). Yamandu Hilbert studies prehistory at laboratoire Archéorient environnements et sociétés de l'Orient ancien (CNRS/ Université Lumière Lyon 2). Maria Guagnin is a researcher at the Max Planck Institute. Rémy Crassard is a researcher at the The French Center for Archaeology and Social Sciences (CEFAS). Pascal Mora is a 3D engineer at laboratoire Archéovision (CNRS/Université de Bordeaux/Université de Bordeaux-Montaigne).

1

Slideshow mode

The archaeologist Guillaume Charloux studies one of the dromedaries sculpted into a sandstone bedrock. Natural erosion has erased most of the traces left by the tools used by the original sculptors.

H. Raguet/Mission archéologique franco-saoudienne du Camel Site/CNRS

2

Slideshow mode

Unable to date the rockface itself, the team excavate the surrounding area for clues. Prehistorian Yamandu Hilbert and Maria Guagnin, an expert in rock art, examine arrowheads and stone tools hoping to retrace the history of the site.

H. Raguet/Joint French-Saudi archaeological mission at Camel Site / CNRS

3

Slideshow mode

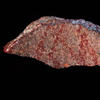

Like most objects found on the surface and in digs at the foot of the sculptures, this rock made it possible to determine when the site was inhabited.

H. Raguet/Joint French-Saudi archaeological mission at Camel Site / CNRS

4

Slideshow mode

The quartz arrowhead was another clue that helped date the site back to Neolithic times, some 8,500 years ago, and to determine that the rockface was carved using stone tools but not metal.

H. Raguet/Joint French-Saudi archaeological mission at Camel Site / CNRS

5

Slideshow mode

The team worked in close collaboration with Saudi authorities in order to protect and promote this unique cultural and scientific heritage. Further study of the site in coming years will help shine a light on this little-known chapter of the Arabian Peninsula’s prehistory.

H. Raguet/Joint French-Saudi archaeological mission at Camel Site / CNRS

6

Slideshow mode

By using Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) technology, the team will try to date when this sculpted fragment detached itself from the bedrock. Scientists Rémy Crassard and Guillaume Charloux (top right) collect a control sample that is continually exposed to sunlight. Another sample, protected from the sun by the fallen block, will be taken in the dark. By measuring the difference in exposure the scientists will be able to ascertain when the rock fell off and have an idea of the minimum age of the engravings.

H. Raguet/Joint French-Saudi archaeological mission at Camel Site / CNRS

7

Slideshow mode

To get an overview of the whole site, Guillaume Charloux and his team surveyed the rock inscriptions and engravings in the vicinity of the giant sculptures.

H. Raguet/Joint French-Saudi archaeological mission at Camel Site / CNRS

8

Slideshow mode

At first these monumental works were linked to the Nabateans and thought to be 2,000 years old. But new fieldwork in late 2018 at what is now called the “Camel Site” revealed much earlier origins.

H. Raguet/Joint French-Saudi archaeological mission at Camel Site / CNRS

9

Slideshow mode

As it is not yet secured, the team made a digital record of the site. Pascal Mora took thousands of photographs which will help him create a digital 3D model of Camel Site. The upside-down legs of a dromedary can be seen sculpted into this fallen piece of rock.

H. Raguet/Joint French-Saudi archaeological mission at Camel Site / CNRS

10

Slideshow mode

Baby on board! In order to be able to participate in the mission, Maria Guagnin brought her baby with her. Her observations and analyses helped to date the engravings as far back as 6,500 BC.

H. Raguet/Joint French-Saudi archaeological mission at Camel Site / CNRS