You are here

Van Eyck was a precursor of augmented reality

The history of lines is anything but linear. The importance of proportions and depth in artistic representation has fluctuated widely from one century and culture to the next. During the Renaissance, the geometric precision of perspective became an essential feature of painting and fresco work, not to mention sculpture and architecture. The topic was famously addressed by the art historian Erwin Panofsky, a seminal figure of the discipline, in his 1927 essay Perspective as Symbolic Form.

Artist-mathematicians?

“At the beginning of the Italian Renaissance, Brunelleschi1 and Alberti2 described perspective in art as a geometrical transcription of the laws of optics,” explains Gilles Simon, senior lecturer at Université de Lorraine and researcher at the Lorraine Research Laboratory in Computer Science and its Applications (LORIA).3 “Their concept was based on the works of Euclid, with the addition of a projection plane between the object being represented and the eye of the viewer.”

Accurate perspective is structured according to a number of mathematical rules, such as the presence in an artwork of baselines converging upon a single vanishing point – a technique that originated with the masters of the Quattrocento and seemed to have been unknown to artists elsewhere prior to encountering the influence of the Italian Renaissance.

According to Panofsky, the Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck attempted to emulate, empirically, the most exact and realistic perspective possible, while remaining ignorant of the underlying geometric laws. And yet Van Eyck was known for his meticulousness. He was one of the first to use oil paints, developing new formulas to obtain slow-drying pigments that would enable him to add more details.

Algorithms for specifying vanishing points

“When I went to see the Ghent Altarpiece, painted by Van Eyck, I was much impressed by the perspective of the fountain in the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb panel,” Simon recounts, “and I decided to dig deeper.” At the LORIA, Simon specialises in the detection of baselines and vanishing points in photographs and videos. The algorithms that he perfects are used, for example, to correct the shapes of objects that have been distorted by the camera angle, or to guide automated systems.

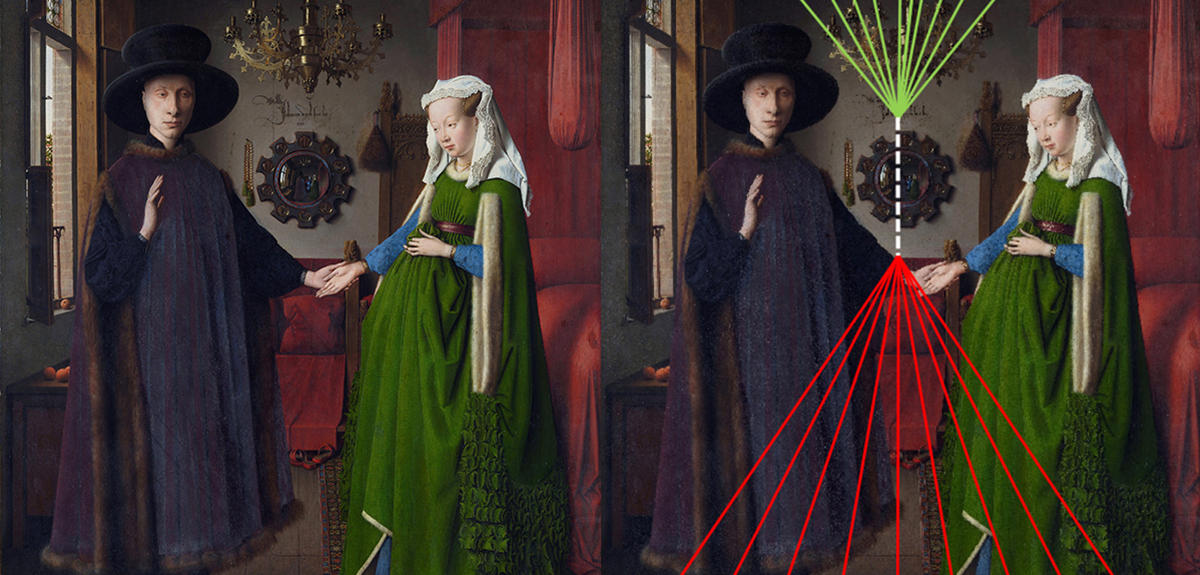

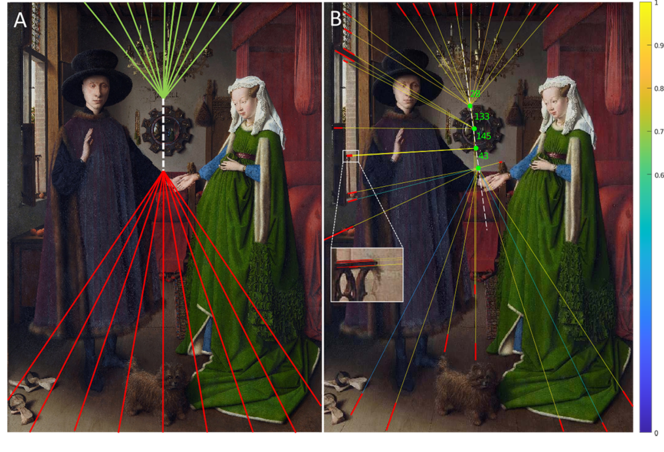

“Whenever I’m in a museum, I can’t help but check whether the perspective of the paintings looks right,” Simon says with a smile. In the case of Van Eyck, he adapted some of his algorithms for detecting vanishing points in order to apply them to five paintings completed between 1432 and 1439. These included the Flemish artist’s most famous work, the Arnolfini Portrait, a painting on wood whose perspective has been the subject of much debate for well over a century.

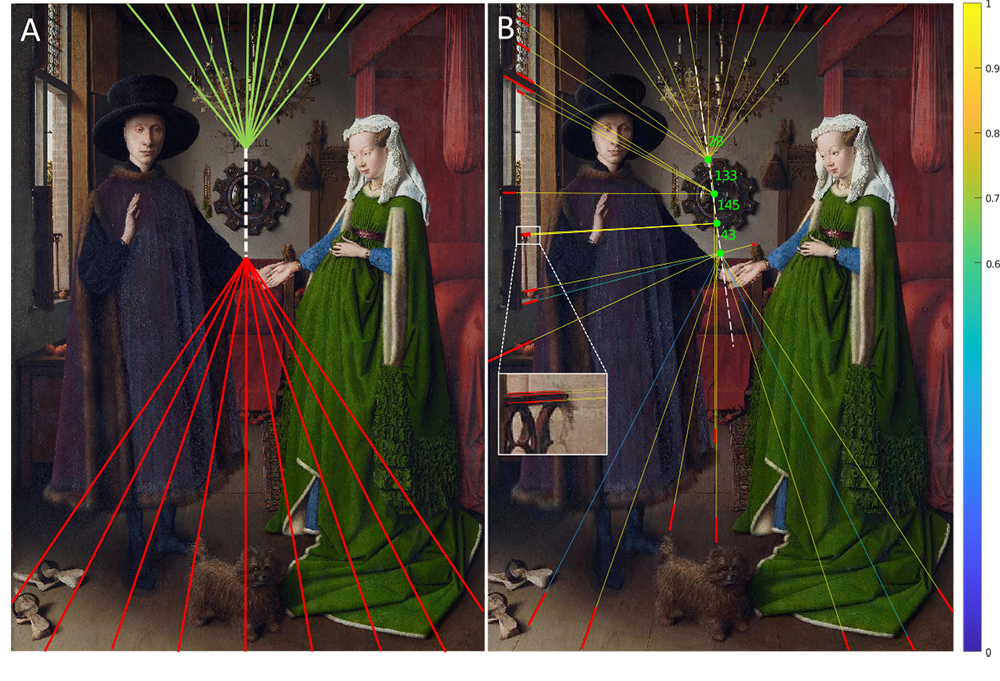

In fact, the identification of what does or does not constitute a vanishing point remains highly subjective. Any and every art historian can add or exclude certain points, perhaps unwittingly. “I integrated uncertainty in the measuring of the edge lines in order to produce a probabilistic map of possible vanishing points,” Simon explains. “I also used an old digital method for establishing the most significant probability peaks.”

A “perspective machine”

The researcher’s analysis reveals that the Arnolfini Portrait comprises four horizontal sections, each with a centric point evenly spaced along an inclined axis traced longitudinally across the painting. Within each section, the perspective conforms perfectly to the geometric principles that were thought to have been known only to a few Italian masters.

While this configuration was not found in the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, all five of the paintings studied revealed a “fishbone” pattern that no one before Simon had identified. His research was made public at SIGGRAPH, an international conference held on 9-13 August, 2021, and published in the event’s journal.

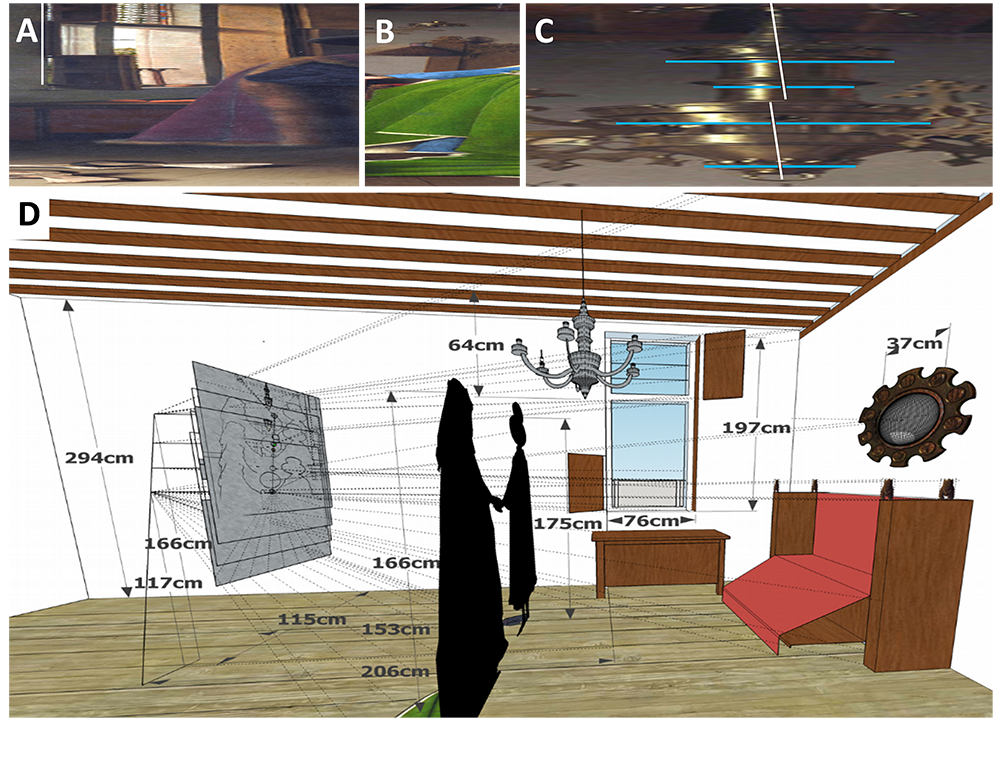

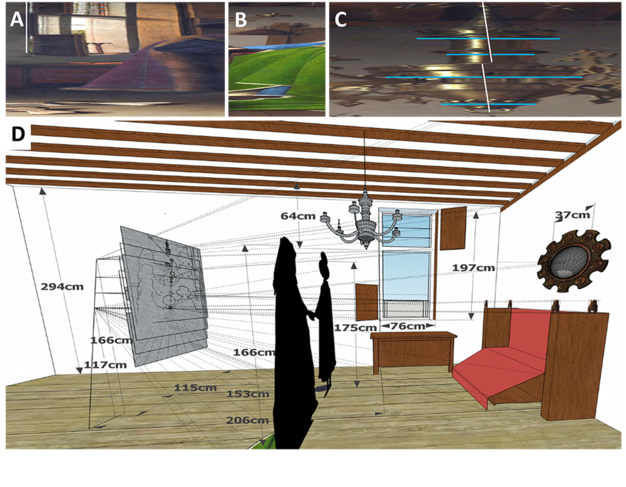

At SIGGRAPH, Simon also presented a 3D reconstitution of the multiple perspective effects in the Arnolfini Portrait, and explained how Van Eyck achieved them. It seems that the painter used a sort of “perspective machine” with four equidistant eyeholes, one for each section, arranged vertically.

“He started by drawing the first section at the very top or very bottom, using one eyehole,” Simon says. “But because of the parallax phenomenon, the image would shift when he switched to the second eyehole. He compensated for this by following an axis in the background, and then proceeded in the same way for the remaining sections. However, with this kind of 3D geometry the alignment can never be perfect. Hence some slight discrepancies in the final painting, especially in the chandelier, which looks as it does because it straddles two sections.”

Anticipating augmented reality

While Brunelleschi was already using a wooden panel with an eyehole by about 1420, Van Eyck nonetheless remains one of the pioneers in the use of optical systems to depict perspective and take human stereoscopic vision into account. This approach can be considered a forerunner of augmented reality, and would be simplified 70 years later by Leonardo da Vinci.

Expanding on his discovery, Simon is now applying his method to works by other artists, and is expecting new revelations on the use of perspective. He also points out that his technique could help authenticate the origin of certain paintings.

Simon’s algorithms are difficult for non-specialists to understand, but he hopes to develop an interface that will allow art historians to use them. “Few of them are interested in digital techniques,” the researcher laments, “but I hope that work like mine will encourage them to use our tools. It has been three full decades since we began proposing solutions that could help them solve their problems of form and geometry.”

- 1. Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446) is best known as the architect of the dome of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence.

- 2. Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), also an architect, notably designed the facades of the Rucellai Palace and of Santa Maria Novella, again in Florence.

- 3. CNRS / University of Lorraine / INRIA.

Explore more

Author

A graduate from the School of Journalism in Lille, Martin Koppe has worked for a number of publications including Dossiers d’archéologie, Science et Vie Junior and La Recherche, as well the website Maxisciences.com. He also holds degrees in art history, archaeometry, and epistemology.