You are here

The World’s Earliest Drawing?

Early humans were a very resourceful lot, managing to fashion a stash of practical tools and implements as old as themselves, dating back three million years. But how far back can we trace their non-utilitarian artistic activities, namely drawing? Until recently, the earliest prehistoric drawings—whether abstract or figurative—were estimated at 40,000 years old. A timeframe now significantly stretched following analysis of a crisscross pattern found on a 73,000-year-old piece of siliceous rock from the Blombos Cave archaeological site in South Africa.

By experimentally reconstructing the technique used to form the crosshatching, the research team representing labs in France, Norway, South Africa and Switzerland, established that the lines were drawn using a crayon.1 A substantial 30,000 plus years older than the drawings previously dubbed the world’s earliest, the abstract motif helps fine-tune our understanding of our distant ancestors, notably by backing up evidence of their usage of symbols.

Prehistoric art offers precious insight into the way early humans saw and represented the world, but—blame fragile composition or exposure to the elements—relatively few artworks have withstood the test of time. Engraving—a comparatively durable form as it involves the scoring of hard surfaces—has left the oldest relics of aesthetic practices, namely “a zigzag incised on a freshwater shell from the Trinil site in Java, Indonesia, found in layers dated to 540,000 years ago,” clarifies Francesco d’Errico, an archaeologist from the PACEA,2 who participated in the Asian discovery in 2015. When it comes to drawing though, surviving works—take the animal depictions and abstract forms in the El Castillo cave in Cantabria, Spain, or those in the Chauvet cave in Ardèche, France—are far more recent, the oldest thought to come in at around 40,000 years old. Until the Blombos discovery came along.

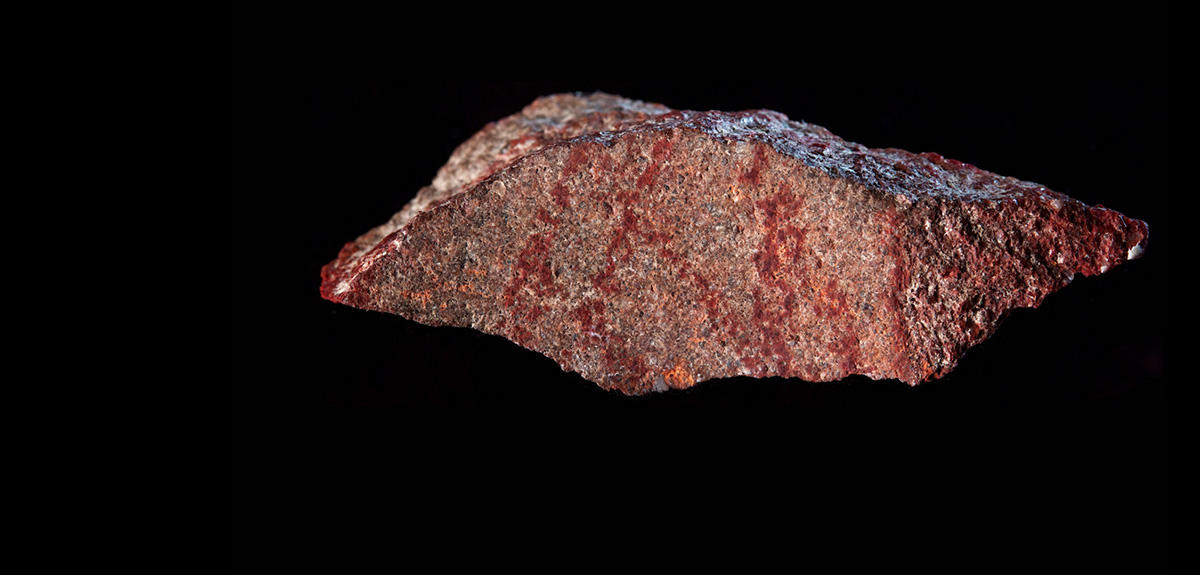

The Blombos Cave, roughly 300 km east of Cape Town, is an excavation site containing Middle Stone Age (100,000-70,000-year-old) deposits. Since digging began in 1991, a sedimentary layer dated to an age of 77,000-73,000 years has yielded numerous items including blocks of ocher stone marked with crosshatch motifs—engraved rather than drawn, however. It was during analysis of stonework debris that one particular flake, dug up in 2011, drew attention: one smooth surface of the siliceous rock fragment bore six straight, virtually parallel lines, crossed by three slightly curved lines. This time not engraved, but showing signs of being drawn.

To verify their suspicions, the team—primarily its members from the French labs PACEA and TRACES3—took a closer look at the flake. “It was a tricky and lengthy process to make this flake speak,” admits d’Errico, who also contributed to the new African study. “It was the first time that archaeologists had come across this type of evidence. So we had to design an appropriate approach, restrict ourself to non-invasive analyses, and make the best use of our equipment.”

Microscopic and chemical analyses revealed the pattern’s reddish lines to be composed of iron-rich ocher, which could only have been applied, since iron oxide does not occur naturally in silcrete. So were the lines a fluke or traced on purpose? The researchers sought an answer by attempting to experimentally reproduce the lines via a range of techniques: using pieces of ocher with either pointed or linear edges to mark strokes on silcrete flakes, or else applying ocher powder mixed with water, at varying degrees of dilution, to silcrete-flake surfaces with wooden-stick brushes. Then, once experimental samples were obtained, a series of microscopy, chemical and tribology (or friction-based) analyses were conducted to compare the motif on the original flake and those produced by the researchers.

Results pointed in one clear direction: the crosshatched lines were deliberately drawn by a pointed ocher crayon—sometimes tracing single strokes, at other times multiple strokes—on a surface smoothed by ancient grinding activity, the flake manifestly detached from a grindstone used to process ocher. Qualifying thus as a drawing, the crosshatch pattern takes over the title of the world’s oldest such work, adding a non-negligible 30,000 years to the previous tally.

And let’s not forget the drawing’s echo of the crosshatch engravings on ocher blocks also retrieved at Blombos. “The observation that Early Homo sapiens in the southern Cape used different techniques to produce similar signs on different media supports the hypothesis that these signs were symbolic in nature and represented an inherent aspect of their spiritual world,” notes d’Errico. That symbols crop up in Middle Stone Age pieces from Africa helps put paid to long-held views that symbols only appeared when Homo sapiens colonized Europe around 40,000 years ago. And while it may be tricky to deduce exactly what the crosshatch stands for, already recourse to it is a “clear indicator of the modern cognition and symbolic thinking” of the area’s long-gone inhabitants, observes the PACEA researcher. Now looking beyond South Africa, d’Errico is “currently investigating the emergence of symbolic practices in Kenya, China and the Ukraine in collaboration with colleagues from these countries and other European institutions.”

But the archaeologist’s research doesn’t just sweep across continents, it also delves into the depths of the human mind: in conjunction with neuroscientists from the CNRS / Université de Bordeaux, he is attempting to “understand how the earliest-known engravings are perceived and processed by the brain.”

- 1. C.S. Henshilwood, F. d’Errico, K.L. van Niekerk, L. Dayet, A. Queffelec & L. Pollarolo, “An abstract drawing from the 73,000-year-old levels at Blombos Cave, South Africa,” Nature, 2018. DOI: XX.

- 2. De la Préhistoire à l’Actuel: Culture, Environnement et Anthropologie (CNRS / Université de Bordeaux / French Ministry of Culture).

- 3. Travaux et Recherches Archéologiques sur les Cultures, les Espaces et les Sociétés (CNRS / Université de Toulouse Jean Jaurès / French Ministry of Culture).

Explore more

Author

As well as contributing to the CNRSNews, Fui Lee Luk is a freelance translator for various publishing houses and websites. She has a PhD in French literature (Paris III / University of Sydney).