You are here

A glimpse of everyday life in the Neolithic

How did our ancestors live 5,000 years ago in what is now northern France? The objects found in many funerary monuments from that period have only provided us with a fragmentary view of everyday life in Late Neolithic societies. "The grave goods found in the collective tombs of the time somewhat distort our understanding," says archaeologist Rémi Martineau, a CNRS researcher at the ARTEHIS laboratory1. To complete the picture, researchers needed to unearth Neolithic settlement sites, initial evidence of which was finally found in the summer of 2023 by Martineau and his team in the Marais de Saint-Gond region, between Reims and Troyes (northeastern France). For the archaeologist, this was "a major discovery been hoping to make ever since started excavating in the region over ten years ago".

First evidence of a settlement

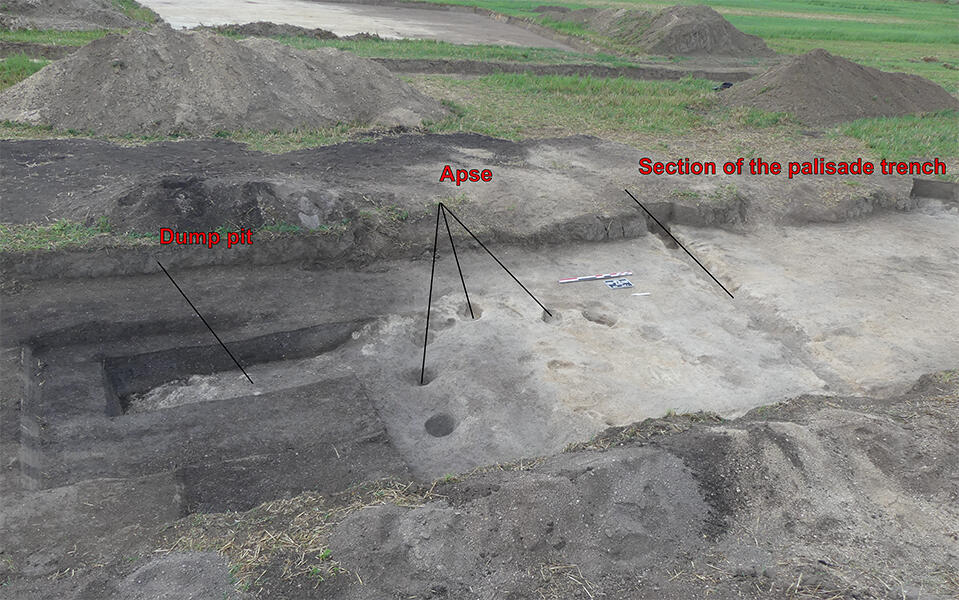

A trial excavation carried out in the Val-des-Marais area with the help of an excavator (which, says Martineau, is an essential tool for archaeologists today, because it can be used to strip huge areas of land) finally enabled them to identify what they had almost given up any hope of finding: the remains of a settlement, complete with fortifications. "Inside a palisaded enclosure, we identified a first building, a well and two large natural hollows used as dumps, all dating from 3600 to 2900 BC," he explains. "The site, which covers an area of 5,000 m2, may actually extend over several hectares."

The building they discovered appears to be a house about fifteen metres long and barely three metres wide, with an apse at one end. "This is a type of architecture frequently found in the following period, the Late Neolithic," Martineau says. The dump pits are collective, a surprising feature that provides an initial clue as to the way the village was organised. They are full of everyday objects, such as pottery (which will help researchers date the site more precisely), millstones for grinding grain, and ornamental objects, probably sewn onto clothing. "We found a button that had never been worn, a unique museum piece made of mother-of-pearl from a species of freshwater mussel called Unio," says the archaeologist, who is hoping to unearth "a lot more archaeological material such as deer antlers, bone and flint tools, milling equipment and so on".

A site explored for 150 years

The Marais de Saint-Gond has been known to archaeologists for over a hundred and fifty years. A keen amateur archaeologist, Joseph de Baye, carried out digs there in the 1870s. He discovered large quantities of chipped flint, which convinced him that prehistoric populations had once lived there. His wealth enabled him to carry out an ambitious excavation campaign during which he unearthed a large number of hypogeums. These are collective underground burial sites dug into the chalk of this limestone region, and are the equivalent of the dolmens found in many other places in France. Unfortunately, he found no trace of the settlements he was looking for.

It wasn't until 1924 that a local archaeologist, André Brisson, used manual probing to identify a promising site in the eastern part of the Val-des-Marais called the “Pré à Vaches”, where most excavations have since been concentrated. Since the end of the nineteenth century, a total of 135 hypogeums, 15 flint mines, 5 megalithic passage tombs, 8 abraders for polishing flint axes, as well as evidence of cultivated fields, have been uncovered in the region.

"Settlements were the missing piece of the puzzle," Martineau explains. "This exceptional discovery should help us better understand how their society was organised, both socially and territorially." Were all the settlements located next to flint mines, or did some of them serve as distribution points? And why are the mines always found next to hypogeums? "Although there are some theoretical models of territorial organisation, this site will for the first time enable us to compare them with archaeological field data," the researcher points out.

An innovative approach

All this is the result of an innovative project and approach. "One of the difficult things about studying prehistory is that researchers have to work with very little data over huge areas and equally vast periods of time. On top of that, everyone specialises in a limited field, such as hypogeums, or farming practices," Martineau says. “I decided to take a different approach to this hyper-specialisation by focusing on a limited region with hundreds of archaeological sites, and by broadening our research to try and find out how Neolithic societies functioned as a whole."

It's a strategy that has paid off: with its mines, tombs, vestiges of agriculture and now its settlements, the Marais de Saint-Gond is home to the only Late Neolithic sites of their kind in the whole of western Europe. The longest and hardest part of the job still remains to be done, namely, the meticulous excavation of the thousands of square metres of land stripped last summer. For Martineau, "the challenge now is to understand the way of life of our ancestors over 5,000 years ago". ♦

- 1. Archéologie, terre, histoire, société (CNRS / Ministère de la Culture / Université de Bourgogne).

Explore more

Author

Fabien Trécourt graduated from the Lille School of Journalism. He currently works in France for both specialized and mainstream media, including Sciences humaines, Le Monde des religions, Ça m’intéresse, Histoire or Management.