You are here

The Genetic Origins of Literary Works

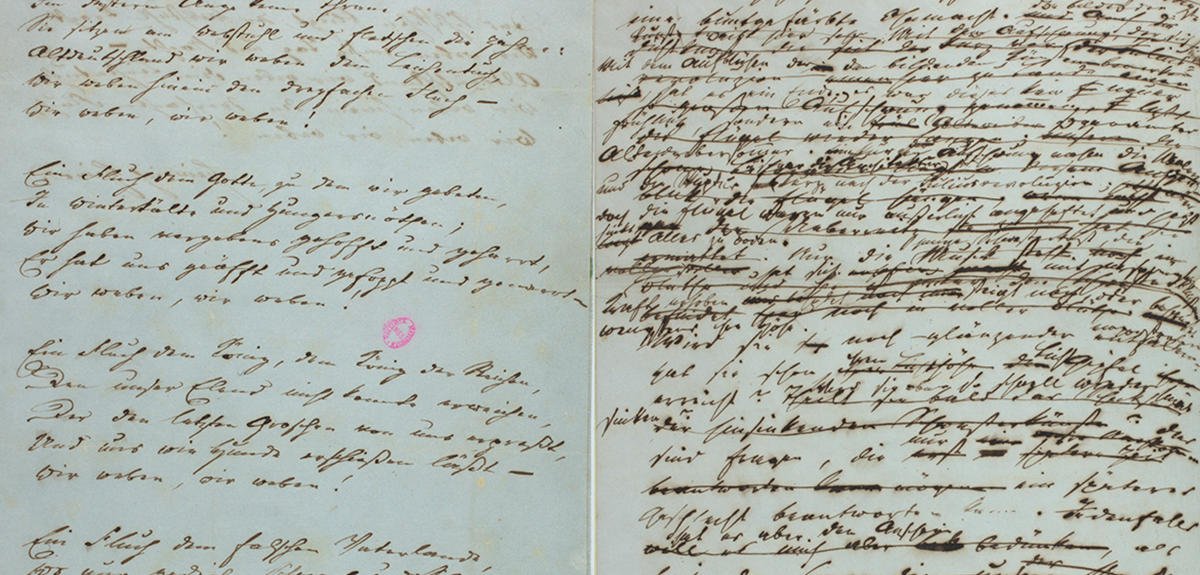

“I think that France should purchase the manuscripts of Heinrich Heine. Signed: C.G.” Fifty years on, Louis Hay still enjoys recounting the thrill that he felt upon discovering that the initials stood for Charles de Gaulle, then president of France. It was in 1967, and the young instructor at the Sorbonne had already spent a few years hunting down the manuscripts of the German poet Heinrich Heine, who was to be the subject of his doctoral thesis. The documents, dispersed in various locations in Israel, Switzerland and the United States, were costly, and the specialist in German language and culture was knocking on every door to seek funding, including that of the French Head of State. “No doubt De Gaulle felt that Heine’s manuscripts were part of our national heritage, because most of them had been written in France,” he explains. The president’s backing was decisive, and the French national library (BNF) began acquiring the famous documents.

Having built up a sizeable collection of Heine’s papers, the BNF was not sure how to handle it: the texts were written in Gothic script, which none of its curators were familiar with. The library therefore asked Hay to categorise them. But he was a literature expert who, by his own admission, knew nothing about archiving techniques. He first convinced two or three other researchers to join in the effort: “Using instruments made available by the CNRS, we learned to identify the types of paper, the inks, the handwriting of the author and of his secretaries… All of the elements that make up the science called codicology, which makes it possible to authenticate and date a text, and possibly to determine its place in the entire body of work.”

The small Heine group, hosted by the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in Paris, set to work in 1968. Their project marked the birth of the discipline that researchers would later call genetic criticism. It led in 1974 to the founding of the Centre d’Histoire et d’Analyse des Manuscrits Modernes. Renamed the Institut des Textes et Manuscrits Modernes (ITEM)1 two years later, it became a CNRS laboratory in 1982. In the meantime, the researchers, by then including several linguists, had begun investigating the manuscripts of Proust, followed by those of Zola, Flaubert, Valéry, Sartre and many others, and genetic criticism became recognised as a full-fledged branch of textual science. “The analysis of all of these documents is aimed first and foremost at defining the historical dimension of the work,” Hay emphasizes. “Our investigations consist in identifying all the material factors and subsidiary networks that could have contributed to the emergence and creation of a literary work,” adds ITEM deputy scientific director Aurèle Crasson.

Heine himself provides a good illustration: he never wrote a book in the strict sense of the term, but rather collections of texts. Piecing them together has shed light on his work. To take another example, Proust’s manuscripts offer an inexhaustible field of research due to the author’s habit of constantly revising the construction of his texts.

As Hay explains, “the opening sentence of In Search of Lost Time—‘For a long time, I used to go to bed early’—is spread out over some ten pages in the first drafts.” Genetic criticism also seeks to understand the hidden reality behind this narrator, who is in fact far removed from the author himself, as Proust’s correspondence reveals. According to the linguist and ITEM senior researcher emeritus Jean-Louis Lebrave, “In studying the drafts, we were able to see how the first person character emerges only gradually, how he is slowly defined in the course of writing the work.”

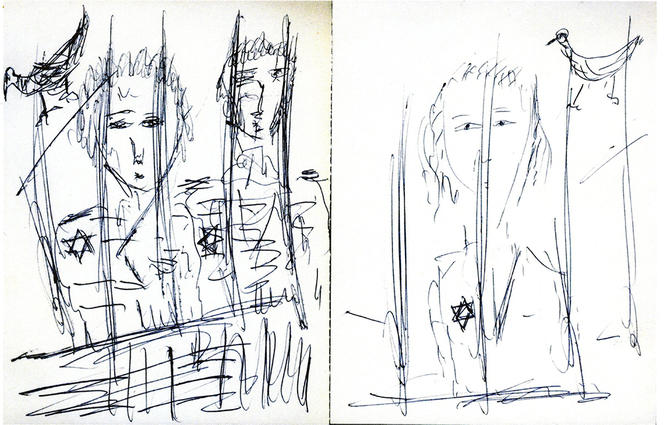

Genetic criticism is also used to identify different authors’ characteristics—what Crasson calls their idiosyncratic elements, often buried deep within their writings. The granddaughter of Edmond Jabès, Crasson painstakingly analysed the drafts of this writer and poet, born to a French-speaking Jewish family in Egypt in the early 20th century. “Jabès was asthmatic and the random rhythm of his breathing is reflected in his writing,” she recounts. “He would leave wide gaps between the parentheses and the text in places, and use much more closely spaced characters in others.” The non-verbal aspect of the creative process is also important, involving “everything that’s not related to language”, Crasson adds. “Jabès said he was incapable of describing the Holocaust. Was it the reason why he resorted to drawing? That’s what we discovered in his manuscripts.”

Topography, or the way in which authors use the page to position their text, is also taken into account in the analysis of the creative process. The manuscripts of Georges Perec, with their widely scattered fragments of text, suggest a work in progress, far from the orderly, methodical impression given by the published work.

Widely recognised in France, as well as in Brazil, Japan and other European countries, genetic criticism has nonetheless been the subject of controversy among intellectuals. Pierre Bourdieu, for example, considered it a mere regression towards classic philology, condemning the discipline for disregarding the structuralist and psychoanalytical revolutions that changed the course of literary criticism in the 20th century. But it has also found a number of prestigious defenders, including Louis Aragon, who came to the ITEM and entrusted all of his manuscripts to its researchers. “Much to its credit, the discipline has introduced specific, objective analytical tools in literary criticism, especially through linguistics,” Lebrave comments. “In a field once dominated by highly subjective interpretations, we have permitted the objectifiable analysis of literary texts.”

Other researchers have significantly furthered this approach. They include ITEM senior researcher emeritus Irène Fenoglio, who conducted an extensive study on the distinguished linguist Émile Benveniste. In fact, genetic criticism has given rise to a new branch of linguistics, “written” enunciation, which identifies, among other things, four essential operations in the production of a text: adding, deleting, replacing and moving. “In short, the four basic functions common to all word processing applications,” Lebrave notes.

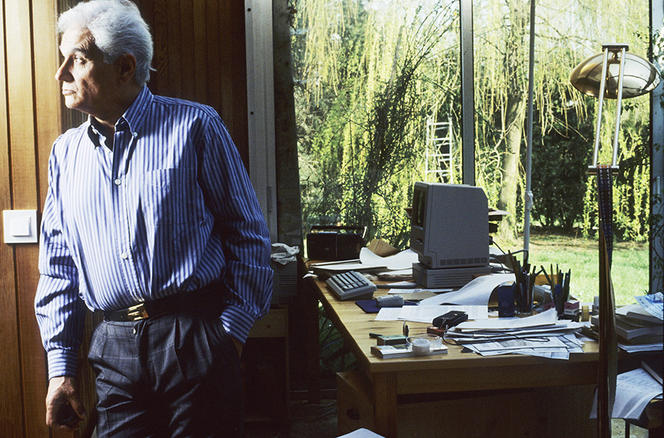

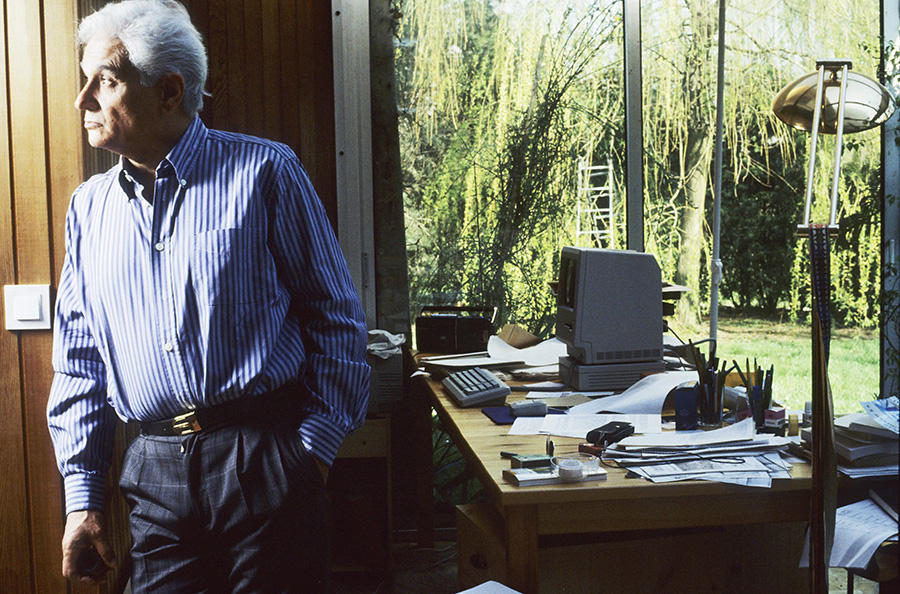

Word processing is indissociable from computers. The latter burst onto the literary scene in the 1980s, and were soon refashioning genetic criticism. Jacques Derrida, who devoted his life to studying the role of language and text in the humanities, is the figurehead of this new phase in the history of the discipline. Very early on, the philosopher anticipated the insidious effects of future online systems and their ability to dispossess authors of their works. Despite his misgivings, he embraced digital technology almost as soon as personal computers became available, starting with a Macintosh Plus, launched in 1986. “He had been keeping all of his archives, down to the smallest scrap of paper, thinking of those who would examine and analyse these records after his death,” Crasson reports. But with the adoption of the computer came that of a new method: Derrida no longer stored the traces of his output. Yet he did not anticipate every eventuality: convinced that deleting a text erased it forever, he did not know that his hard disks were keeping a record of all of his operations, and that 21st-century literary researchers would one day use forensic IT techniques—in other words, scientific methods developed for criminal investigations. “With Derrida, we entered into the exciting adventure of hard disk analysis in which we try to restore the deleted versions of the author’s texts based on the remaining non-overwritten digital data,” Crasson says.

Of course, a hard disk does not save everything. Scribbles, sketches, the rhythm of handwriting… Many types of clues have disappeared with the advent of computers. Still, Hay is not nostalgic for the pre-digital era: “Because processors keep a record and the date of every step in the writing process, we can retrace the various drafts and work phases with extreme precision.” The founder of genetic criticism is even looking forward to a new technological revolution: the use of voice command to replace the keyboard, which will require scientists to adapt their methods once again.

Meanwhile, the ITEM team, along with some 300 other researchers worldwide studying the creative process, intend to further broaden their field of investigation, which they have already extended beyond literature. Philosophy has become one of their focal points, with Nietzsche, Sartre and more recently Derrida, as well as music, architecture and visual arts like drawing, photography and cinema, which have led them to venture into the realm of collective creation. Let it be said in the laboratories: the history of the sciences is also of interest to genetic criticism. Physicists, biologists and climatologists may one day find themselves under the ITEM’s “forensic” scrutiny, capable of retracing the genesis of a breakthrough from a note jotted down on the corner of a lab bench until the official announcement at the Academy of Sciences.

- 1. Institut des Textes et Manuscrits Modernes (CNRS / ENS Paris).