You are here

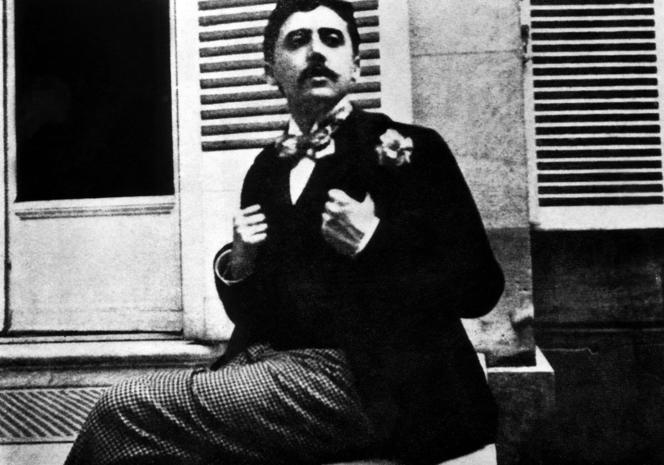

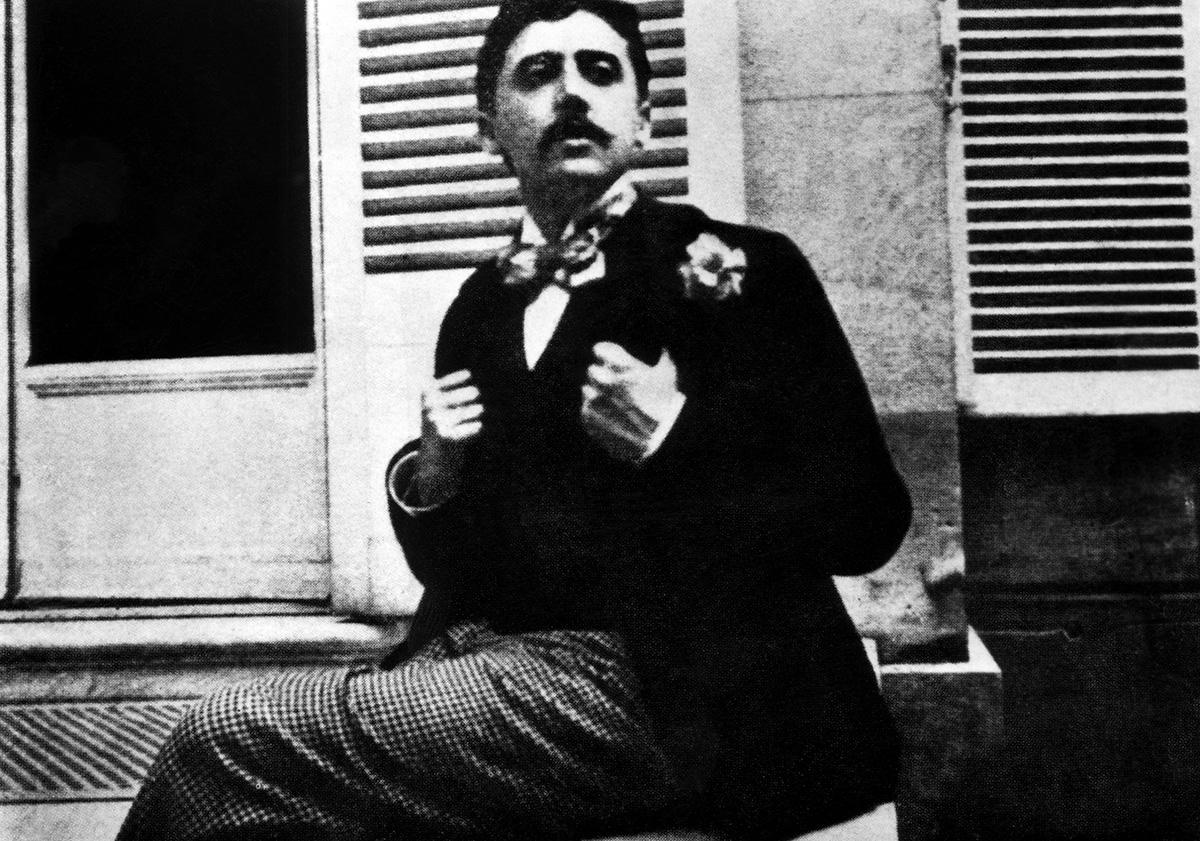

Proust’s Letters To Go Online

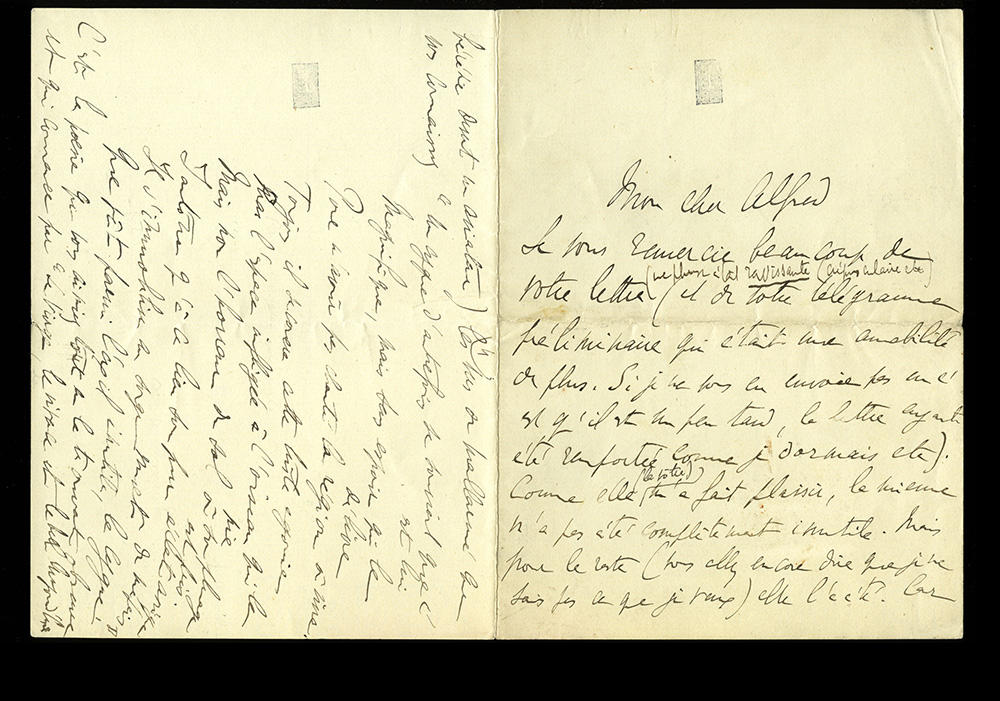

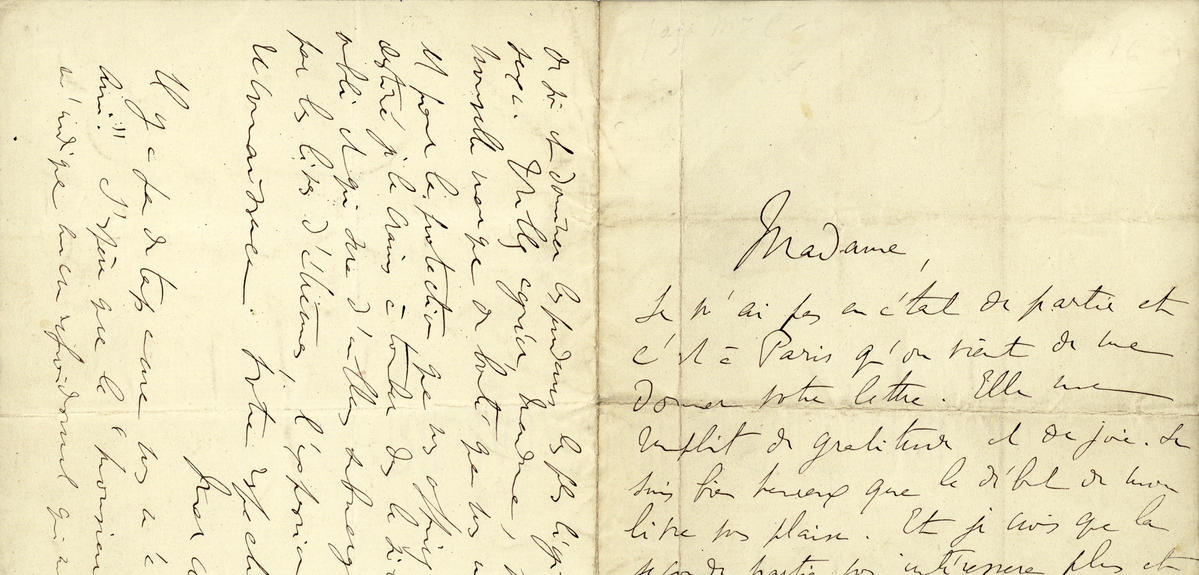

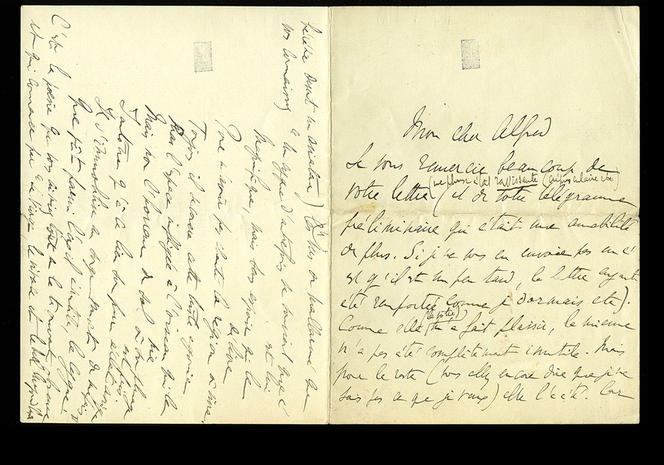

“For some time now I have been having bad moments, beset by a new affliction. A simple letter is difficult for me.” In this message to Lucien Daudet from 1909,1 as in many others, Marcel Proust complained of the difficulties he experienced in writing even a few lines. And yet, his collected correspondence is estimated at 20,000 letters or so, if one includes all the telegrams, dedications, notes of condolence, etc. Some of his letters are so long that he summarized their key points in a PS at the top of the first page, as though fearful that his correspondents wouldn’t have the perseverance to read them all the way through! Of this huge mass of documents, not all have been found or preserved, but nearly 6,000 have been collected and included in various publications, especially the famous Correspondance de Marcel Proust edited in 21 volumes by the US professor Philip Kolb.2 This exceptional collection is constantly evolving as rediscovered letters and texts come to light, to the point that Correspondance has become nearly illegible on paper due to all the updates in the form of notes and appendices.

A Franco-American collaboration

The “Corr-Proust” project aims to overcome this unwieldiness while greatly expanding the scope of the archive by making it accessible on an Internet platform in the near future. The website will be the result of a massive digitization effort undertaken by the “Proust 21” consortium, an association uniting the University of Illinois "at Urbana-Champaign" in the US, which owns about 1,200 of Proust’s letters, the ITEM,3 and the Litt & Arts laboratory of the Université Grenoble Alpes.4

The project is a remarkable example of collaborative research, but above all a great step forward in the “digital humanities,” i.e. the use of new IT resources for the benefit of philology, the arts and human sciences. An initial series of 200 letters related to World War I will be made available online this year to coincide with the centennial of the Armistice of November 11, 1918.

Other projects of this type, like the digital edition of Gustave Flaubert’s manuscripts for Madame Bovary released by the University of Rouen, have already pioneered this interdisciplinary field, but the Corr-Proust project seeks to go much further. “We waited for an upgrading of IT resources in order to create enriched data, with different types of tags to enable multiple angles of research,” explains Françoise Leriche, a professor at the Université Grenoble Alpes who serves as scientific supervisor of the project. A former assistant of Philip Kolb, the US professor at the University of Illinois who, starting in the 1970s, edited in 21 volumes all of Proust’s correspondence that he could find, Leriche welcomes the possibilities offered today by XML (Extensible Markup Language). Well-suited for complex content, this programming language can restore the various layers of text, integrating the author’s successive corrections, additions and deletions. In the case of Proust this can be a veritable textual labyrinth, even though his letters were subject to much less revision than the thousands of draft pages of In Search of Lost Time. XML also allows the researchers to reproduce the letters in “diplomatic version,” following the exact layout and configuration of the documents, including, for example, sentences written diagonally across the page.

Expanding the field of investigation

All of this was not achieved overnight. “In the early 2000s, it was not easy to convince computer specialists to work on this type of literary publishing project,” Leriche reports. “On a literary research team, especially in a small university, there simply weren’t any developers or computer engineers!” Refusing to give up, she eventually persuaded Thomas Lebarbé to join the effort: the young professor in Digital Humanities at the UGA had recently developped the XML transcription tool for the digital edition of Stendhal’s manuscripts.

There ensued a long communication and discussion phase to make certain that all of the literary and IT researchers were “on the same page.” In fact, the text itself only makes up one part of the multiple types of data to be described and encoded. These also include the quality of the paper, which often enables to determine the period during which the letter was written—an important point, since Proust rarely dated his correspondence. Then there is the writing medium (pencil, fountain pen, typewriter), the geographic location, etc. “Encoding these various elements will make it possible to search, for example, for each and every letter that Proust wrote at the Hôtel des Roches Noires in Trouville (Normandy), or, in a different vein, to find all the quotes he used or mentions he made of various institutions,” Leriche explains. “In short, we want to offer access to the widest possible fields of investigation, even if part of them may never be used.”

The narrator and the writer

The system can also reproduce photos, newspaper clippings and other documents that the novelist sometimes enclosed with his correspondence. Indeed, his letters form a composite portrait of Proust both as the an incomparable observer of the subtleties of human relations, and as a man of his time.

And this is precisely where this correspondence provides new insight into In Search of Lost Time. The real-life Proust that emerges is far removed from the popular image of the reclusive, sickly writer confined in bed. On the contrary, he turns out to be an avid reader of the press, keeping up with the news (he closely followed the Dreyfus Affair, the international tensions of the day and the developments of the Great War), expressing his curiosity about everything from literature to technological progress and automobiles, and paying close attention to the stock market.

“His correspondence clearly shows that the narrator of In Search of Lost Time is not Marcel Proust!” exclaims Nathalie Mauriac Dyer, who in addition to heading the ITEM team is collaborating with the Bibliothèque Nationale de France on a diplomatic edition of the drafts of Proust’s masterpiece. “The narrator is an invented character, an idealized writer who can devote himself entirely to his work.” The letters also make it possible to read between the lines of the novel, which according to Mauriac Dyer is peppered with private jokes, sly references to the author’s friends or, on the contrary, discreet settlings of personal scores. Proust’s correspondence lacks neither humor nor bitchiness, an example of the latter being his rebuke of the Nouvelle Revue Française, which had rejected his first manuscripts, in a letter to Jean Cocteau from 1919 or 1920: “If one of these days you have the time to tell me in person how you conceive your work, I will spread the word to the NRF, which always greets me by sending me packing (but not about you, of course)…”5

Proust’s correspondence reveals a man keen to maintain relations with all social backgrounds (he wrote to concierges, quoted household staff…), and for whom everyone had the same human value—in other words, not at all the snob that people often imagine, never venturing beyond the confines of Parisian high society. It also brings to light a writer who is more levelheaded than his narrator, avoiding certain prejudices of his time, like reflex anti-German sentiment. And a meticulous author, who once asked a scientist he knew whether one could say that eggs “coagulate” at a certain temperature.

A cultural treasure

The project will give ammunition to the many researchers the world over who continue to analyze Proust’s works. Internationally recognized in his own lifetime, the author is globally considered one of the greatest representatives, if not the greatest, of French culture and literature. The discovery last summer of a short amateur film from 1904, , showing a young man looking somewhat like Marcel Proust (but which could not be him) on the steps of the Eglise de la Madeleine in Paris after an aristocratic wedding, was even reported in the New York Times!

Universities across the world, especially in Japan, are engaged in purely “genetic” analyses of In Search of Lost Time, reconstituting and studying the different stages in the writing of the novel. And there are countless research topics related to the work itself. After the Proust associated with psychological and human relations, and that of the “New Criticism” of the 1960s, focusing on psychoanalytical approaches or questions of narration, “today’s research looks into the novel’s underlying cultural history,” Mauriac Dyer notes. “Indeed, the work is an immense trove of literary, as well as musical, theatrical and political references from the time of the Third Republic.”

This approach also encompasses questions of morality. “The way Proust presented his homosexuality and his Jewishness, which for him were always linked, finds resonance in the modern-day debates on gender theory and political minorities," the researcher adds. "Although ubiquitous in his work, these issues are addressed in a more or less allusive or concealed way. Now it’s a matter of bringing them to light.”

- 1. Letter from March or April 1909, held by the Rare Book & Manuscript Library at the University of Illinois (US).

- 2. Marcel Proust, Correspondance, edited by Philip Kolb, Plon (1970-93, 21 volumes).

- 3. Institut des Textes et Manuscrits Modernes (CNRS / ENS / Université de Poitiers).

- 4. Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA) / CNRS.

- 5. Letter to Jean Cocteau, Bulletin d’Informations Proustiennes, 47, ITEM 2017.