You are here

The Internet, a disinformation highway?

Fake news, the modern name for a very old social phenomenon. Dating the emergence of such falsified assertions would be an uncertain exercise, as the deliberate distortion of facts by individuals, groups, and governments seems to have always existed. The objective has ranged from tarnishing the reputation of a figure to discrediting a political opponent, questioning a scientific fact, or pretending to unveil a secret plan for world domination, in short tampering with facts to manipulate public opinion. Even so, some believe that humanity has never been awash in such a sea of both real and fake news. "Fake news has become the major driver of recent electoral campaigns, from the pro-Brexit campaign in the United Kingdom to the election of the Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro, along with various elections in Europe and the United States," points out Émeric Henry, who is a Professor in the Economics Department at Sciences Po.1 Similarly, much fake news, such as that spread by the documentary Hold-up, which was released in November 2020 and viewed millions of times on the Internet, has circulated in connection with the Covid-19 pandemic.

In fact, digital platforms—and social media such as Facebook or Twitter in particular—now play a major role in the virality of content, whether it adheres to the truth or is intentionally misleading. A formidable sound box, the Internet is a boon to manipulators of public opinion. It all begins with the fact that "the model for these platforms is based on sharing above all else, since their advertising income depends on the amount of activity," Henry explains. Social media algorithms, which are far from neutral, were not designed to sort true from false, but rather to select, classify, rank, and target news likely to capture the attention of a maximum number of users.

A "bonus" for emotion and controversy

"The more a user spends time on a platform, the more it can display ad inserts, and the more its revenue increases," says Antonio Casilli, Professor of Sociology at Télécom Paris, and a member of the Interdisciplinary Institute on Innovation.2 "However, the algorithms that determine each user's news feed are optimized to underscore striking messages that provoke strong emotional reactions. A sort of ‘bonus’ for emotion and controversy, which then prompts the user to extend their connection. This is why the most outrageous fake news circulates so widely." While the platforms are enriching themselves, the same is not true for everyone else: "According to a 2019 study,3 the cost of fake news in terms of stock market losses, public health risks, damage to brand image, and electoral campaign spending is estimated at $78 billion."

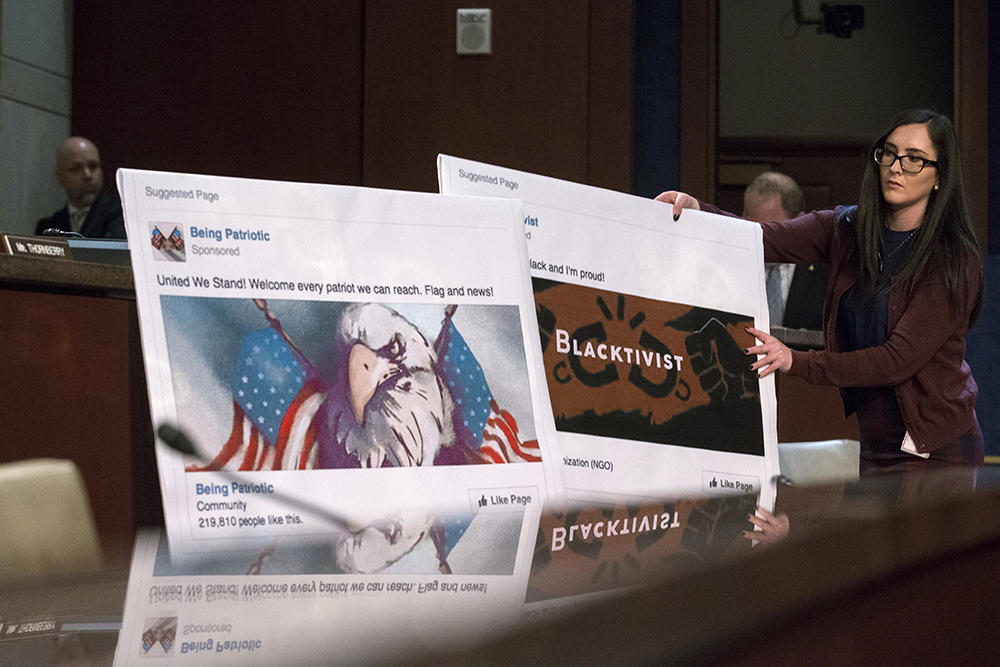

Governmental offices, political parties, activist groups, business sharks, and other clever digital geniuses use various ploys for such operations, beginning with the use of fake profiles at "troll factories," such as the Internet Research Agency in Saint Petersburg, which has close ties to the Kremlin, and was particularly active during the 2016 US presidential election.

"Such efforts specializing in aggressive communication rely on scores of operators to pour forth false remarks on social media," Casilli continues. "These little invisible hands, who are paid a few cents per message, are mostly located in emerging or low-income countries. The fake news produced in this manner are then be transmitted by semi-automated accounts (bots) that can interact with real people. These programmes that tweet very frequently, day and night, especially toward influential accounts, amplify the circulation of fake news." These are so many tools used to organize propaganda campaigns, such as astroturfing (reference to the American brand AstroTurf, which sells synthetic grass, hence an imitation of the real thing). This practice involves simulating a spontaneous shift in public opinion by a limited number of actors.

Social media regulation and democracy

"By inundating social media with fake accounts, the person giving the orders and a few associates can give the impression of a broad-based citizen movement," Casilli adds. "The architects of Éric Zemmour's Internet policy used a limited number of Twitter accounts (‘Teachers for Zemmour,’ ‘business owners for Zemmour,’ ‘members of the military for Zemmour,’ etc.) to have the polemicist appear regularly among the trending subject on Twitter, thereby creating the illusion of civil society rallying behind his ideas."

Various responses are being explored in the face of such manipulation. Germany adopted a law that issues a 50 million euro fine to platforms that do not remove illicit content that was reported to them. In late 2018, the French Parliament passed a law giving judges the power to block, for 48 hours, content or websites spreading fake news during election periods. However, entrusting the courts with the formidable task of distinguishing between true and false—at the risk of trampling freedom of speech—is open to discussion.

Similarly, the self-regulation efforts pursued by social media giants have left many doubtful. "Their core business is to generate profits, not to moderate content that could endanger their growth," Casilli reminds. Platforms are therefore content to do the minimum to avoid public outcry, thereby avoiding being subject to more restrictive state regulation, which could prove catastrophic for them. Some observes who are concerned for democracy are nevertheless advocating for the possibility of ad hoc governing bodies to audit the algorithms of certain platforms.

Checking facts, a misguided idea?

What about fact-checking units? Created by traditional media ("The Decoders" at Le Monde, "Detox" at Libération), their usefulness has raised doubts. Proof of this came in the experiment conducted by Henry on 2,500 individuals representative of the French population, as part of the 2017 French presidential election.4 "We gave some participants statements from Marine Le Pen based on erroneous statistics regarding migrants, while the others received the same quotations followed by corrections from official sources such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE)," Henry says.

The people who were given the fact-checked statements remembered the official figures, and improved their factual knowledge of immigration, but this had no effect on their opinions or voting intentions. "Their initial impressions persisted despite the corrections, and the emphasis placed via fact-checking led to even more anxiety surrounding the topic!" This would explain why even when not exposed to the institutional statistics, participants supported the Rassemblement national party at even higher rates after the experiment than those who were not exposed to these figures."

A more reassuring study on the effectiveness of fact checking, forthcoming in the American Economic Journal, was conducted in 2020 by Henry among a similar sample size. "We provided Facebook users with false content regarding Europe. The participants who were informed of this through fact-checking, which was either imposed or made available as an option, proved much less inclined to repost them than those who were given just the fake news. The sharing of fake news in this group decreased by 30-45%." A 2020 experiment5 also showed that "to avoid looking like an idiot, American participants in a study resisted the temptation to forward fake news," comments Hugo Mercier, a researcher in cognitive science at the Jean-Nicod Institute.6 "As is true for the media, politicians, and institutions, the practice proved very costly in terms of their reputation and credibility, given that it is easier to lose than to earn."

Credible news is also spreading

Another set of results7—often cited in the media ranging from CNN to television news across the globe—sends chills down the spine regarding the spread of news. It shows that on Twitter, fake news of a political nature can reach 20,000 people in one-third the time it takes "real" news to reach 10,000. Yet according to Mercier, "summarising what happens in our lives in this manner is completely false. An important fact must be taken into consideration, namely that the majority of 'real' news is never verified given how obvious it is. For example, no fact-checking was ever published for Emmanuel Macron's election victory in 2017, whereas the news tested in the study all emerged from corrections, thereby making the sample far from representative of the immense quantity of real news that circulates."

The same is true for fake news, for only those items that circulated widely—and thus drew the attention of fact-checkers—were included in the study’s samples, whereas the ocean of fake news that does not enjoy such success no doubt circulates much more slowly. "It seems to me that credible news spreads much more quickly than fake news," affirms Mercier, going against the grain of the prevailing sense of concern.

Reducing the acceptance of fake news to zero

Mercier is partly basing his opinion on his most recent research. He and his team showed that a very slight increase (1-2 %) in the acceptance of credible news is equal in effect to reducing the acceptance of fake news by Internet users to zero,8 as the latter represents only a small portion of the information consumed by the population (a few per cent).

"To obtain this result, we integrated within our mathematical model public data regarding the prevalence of fake news. Rather than count individual articles, this data sorts articles by website, focusing on ‘spreader’ sites that generate a great deal of traffic, namely major media outlets, which are systematically monitored by fact-checking, and popular but less official sites, which also drew the attention of fact-checkers." Once again, the news that "Macron was elected president in 2017" was surely not checked. However, whether mainstream (major mass media outlets, as opposed to so-called alternative media) or not, at least the source site was taken into account in the resulting ratio, which makes Mercier optimistic regarding the issue.

The research on which Mercier and his colleagues based themselves indicates not only that fake news represents a tiny portion of news on Facebook and Twitter,9 but that it is driven by a very small number of individuals.10 "Actually, most internet users are almost never exposed to fake news," Mercier adds. When it does happen, "humans are less credulous and manipulable than we think. We all have psychological mechanisms that make us suspicious of new information. Faced with a novel proposition, these cognitive faculties make us question the reliability of the source and the credibility of its content, allowing us to foil most attempts at mass persuasion emanating from the media, advertisers, and politicians," he observes, based on his most recent essay reviewing the relevant literature in psychology.11

Does digital technology tear apart the social fabric?

"We even tend to reject too much real news, as observed in our study cited above." Their results indeed showed that while participants accepted 30% of fake news as real, they also deemed 40% of credible news to be false. "This can of course have pernicious effects in certain situations, for example with respect to vaccination, if the news explaining its benefits is rejected. As our colleague Alberto Acerbi12 has shown, the fake news that spreads the most is essentially gossip regarding celebrities, or news relating to aversion or sex, which does not greatly disrupt the functioning of democracy. A number of studies13 have shown that fake news that is political in nature, or within the context of a crisis, fear, or danger—raising fears of a wide effect on public opinion—is almost exclusively consumed by people that already agree with the point of view expressed. It is therefore not very likely that it will lead to major socio-political upheaval."

Yet social media and fake news are regularly singled out as flawed "facilitators" of public panic, for instance with the invasion of the Capitol14 on 6 January 2021 in Washington, DC by Trump supporters convinced that the election was "stolen" from him, or the 2016 demonstration "organised" in Houston by the Internet Research Agency in Russia via the "event" option to promote the election of Donald Trump, or various anti-vaccine demonstrations, in which many people believed fake news.

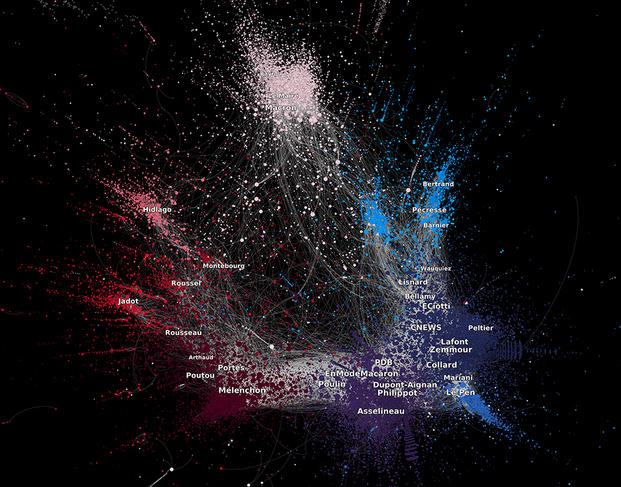

The mathematician David Chavalarias, Director of the CNRS's Complex Systems Institute of Paris Île-de-France, has modelled the manipulation of public opinion by mass data generated on Twitter in connection with the French presidential election. Does digital technology tear apart the social fabric? "The use of social media is not even twenty years old. We do not have a lot of perspective on the country-wide impact it has on how social life is organised," he pointed out in an interview a few months ago, all while worrying that our democracies will experience populist movements in the future due to the manipulation of public opinion that is inherent to the business model of major digital platforms.

Making clicks more complicated

Whether the virality of fake news—or its quantity and pernicious effect—are overestimated or not, everyone agrees that it must be combatted. One strategy proposes making it more complicated to share messages. "The idea is to make this act, which today can be executed in a single click (‘like,’ ‘retweet’), a little more complicated," Henry goes on. "This would involve making users confirm their intention by clicking on a link reminding them that forwarding fake news can have serious consequences." One test showed that this effort reduced the sharing of fake news by 75%15! "However, implementing such a measure appears difficult," reacts Casilli. "Tech giants such as Facebook and Amazon have been working hard since 2010 in the opposite direction, namely to share information 'in one click' or 'seamlessly.'"

Another approach, both traditional and popular, is to provide "media education" courses to help youth (and those who are not so young...) hone a critical spirit toward digital dupery. In short, this involves adapting to new information technologies, just as we have always done since the appearance of the printing press, photography, or video, which do not always tell a true story.

- 1. CNRS/Paris Institute of Political Studies/Sciences Po Paris.

- 2. CNRS/École polytechnique/Mines ParisTech/Telecom Paris.

- 3. “The Economic Cost of Bad Actors on the Internet,” Roberto Cavazos, Cheq, University of Baltimore, 2019.

- 4. “Facts, Alternative Facts, and Fact Checking in Times of Post-Truth Politics”, O. Barrera, S. Guriev, E. Henry and E. Zhuravskaya, Journal of Public Economics, vol. 182, 2020.

- 5. “Why do so few people share fake news? It hurts their reputation,” S. Altay, A. S. Hacquin and H. Mercier, New media & society, 24 Nov. 2020.

- 6. CNRS/ENS-PSL.

- 7. “The Spread of True and False News Online,” S. Vosoughi, D. Roy, and S. Aral, Science, vol. 359, no. 6380, March 2018.

- 8. Research note: “Fighting misinformation or fighting for information?”, A. Acerbi, S. Altay, and H. Mercier, Misinformation Review, 12 January 2022.

- 9. “Evaluating the fake news problem at the scale of the information ecosystem,” J. Allen et al., Science Advances, vol. 6, no. 4, April 2020.

- 10. “Fake news on Twitter during the 2016 U.S. presidential election,” Grinberg et al., Science, vol. 363, no. 6425, Jan. 2019.

- 11. Not Born Yesterday: The Science of Who We Trust and What We Believe, H. Mercier, Princeton University Press, 2020.

- 12. “Cognitive attraction and online misinformation,” A. Acerbi, Palgrave Communications, vol. 5, no. 15, 2019.

- 13. For example: “Selective Exposure to Misinformation: Evidence from the consumption of fake news during the 2016 US presidential campaign,” European Research Council, A. Guess, B. Nyhan, and J. Reifler, 2018.

- 14. The House Select Committee to investigate the attack on the Capitol released its conclusions in mid-June 2022. It details the many forms of pressure exerted by Donald Trump on his Vice President Mike Pence to prevent him from certifying Joe Biden's victory in the American presidential election.

- 15. “Checking and sharing alt-facts,” E. Henry, E. Zhuravskaya, and S. Guriev, American Economic Journal, June 2020 (preprint).

Explore more

Author

Philippe Testard-Vaillant is a journalist. He lives and works in south-eastern France. He has also authored and co-authored several books, including Le Guide du Paris savant (Paris: Belin) and Mon corps, la première merveille du monde (Paris: JC Lattès).