You are here

The Rise and Fall of Innovation

What does the videophone1 have in common with disposable underwear and pickle-flavored toothpaste?2 They are all flops. Or rather novelties that never caught on. “In the industrial world, seven to nine innovations out of every ten are expected to fail,” notes Bernard Darras, a semiotician at the Institut ACTE.3 Some 20 researchers from the ACTE Institute are collaborating to create a documentary database of these “by-products of modernity” from the late nineteenth century to the present day. The CNRS-sponsored project, entitled “Archaeology of Abandoned, Neglected or Resurgent Innovations,”4 involves a description of each object, along with its history, photos, videos, and analyses by researchers and engineers. It aims to examine the notion of modernity— and give innovators in every field an unbiased perspective on failure.

The Bi-Bop: a textbook case

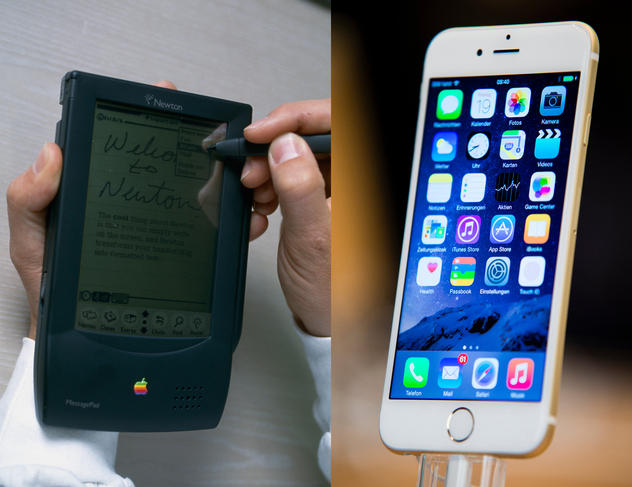

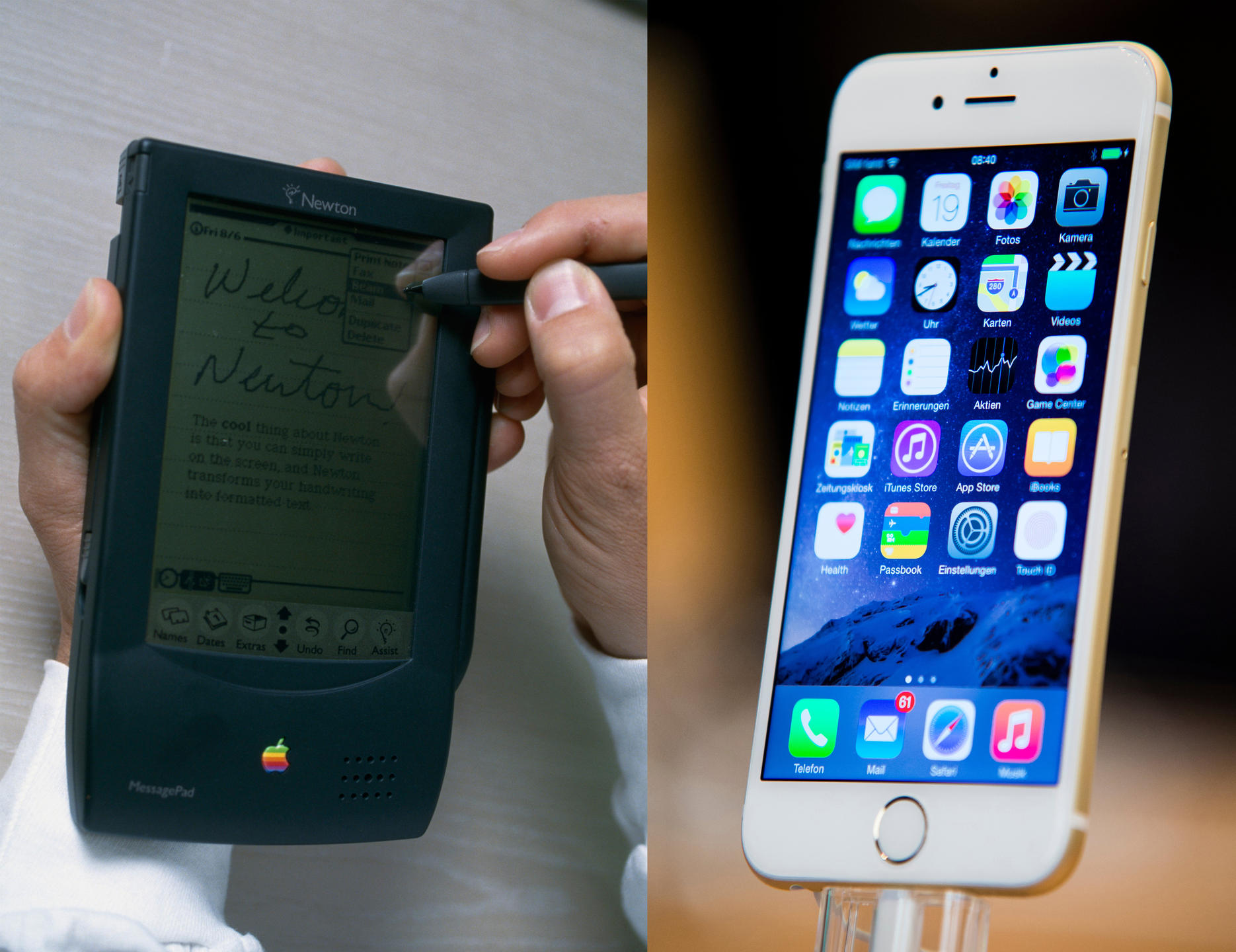

Yet failure is not easy to define. “Sales or usage figures can be an indicator, but the history of innovations should also be taken into account: can they be called failures when they are initially abandoned but re-emerge later, in the same or a different form?” ponders Norbert Hillaire, theoretician of technologies and researcher at the ACTE Institute. Darras would rather see them as “tries that need to be converted,” to use a rugby metaphor. Indeed—and as entrepreneurs like to say—being right too early is the same as being wrong. And examples abound, like Apple’s Newton, a personal digital assistant launched in 1993, met with irony and discontinued in 1998, before being reintroduced in 2007 in a much-improved version under the iconic name of “iPhone.” In a similar vein, France has had its own emblematic communications flop with the Bi-Bop, the country’s first cell phone. Launched in 1991, it operated on a specific network of radio antennas that were set up in city centers. Users could receive and make calls, as long as they were close to one of these antennas, much like Wi-Fi works today. But a limited network of terminals (whose faded blue, green and white-striped stickers can still be spotted in Paris) and the advent of GSM cell phones in 1997 led to its demise.

The need for failure

“In our classification, we distinguish between ‘premature’ or ‘resurgent’ innovations and those that proved inadequate and doomed to failure,” say the researchers. The high-speed moving walkway in the Montparnasse-Bienvenüe Metro station in Paris falls into the latter category. Accelerating to the breakneck speed of 11 kilometers per hour, it was supposed to shave 90 precious seconds off the user’s average travel time, but was finally abandoned in 2009, after seven years of repeated breakdowns and falls.

“Most interesting, in my opinion, are innovations that are disregarded for some time, and eventually make a comeback,” Darras adds. The monocle, for example, fell out of favor in France after the Franco-Prussian War for being too reminiscent of the enemy. “ Yet it seems to have reappeared in high-tech form in the 2010s as Google Glass, whose headsets have a single optical zone with a camera,” the semiotician points out. Revival was short-lived though, as production was suspended in January 2015 due to deterring prices and hostile public reaction. Still, the Wall Street Journal hints that the device may soon rise from its ashes.

“It is often a matter of time: how long does it take for a failure to become a success, and can it fail again?” Darras asks. Hence the choice of “archaeology” of innovations as a name for the project, championed with the CNRS by Richard Conte, director of the Institut ACTE.

In fact, the fear of failure seems to be more daunting in France than in other countries. For many French people, it is “the equivalent of social suicide, whereas in the US… failure is a learning experience,”5 asserts Jevto Dedijer, former marketing director of Ikea France. “The problem in France is that the educational system condemns failure, leaving engineers reluctant to take any risks,” Darras explains. “Our documentary database seeks to break the mold and show that success often results from a string of trials and dead ends. We hope to change people’s attitudes.”

try to discover

new findings

Darras and his colleagues are not alone. “Conferences dedicated to the sharing of entrepreneurial failures” have been held in France in the past few years in order to “learn from the mistakes of others,” points out the entrepreneur Boris Golden.6 Often cited as reference is the versatile manufacturer Bic, which brought ballpoint pens, disposable razors, and lighters into every household, but suffered a severe setback with low-priced perfume. Another indicator of change is that, since 2013, France’s central bank has only indexed fraudulent bankruptcies,7 whereas its “blacklist” used to include all entrepreneurs who had filed for bankruptcy in the previous three years, no matter the reason.

A philosophical challenge

Do the ACTE researchers also seek to reduce the seemingly inevitable 70-90% failure rate for innovations by “predicting” the non-starters? Are they hoping to rationalize the development process in order to prevent failure? “On the contrary,” Darras explains, “I believe in serendipity, which in 1928 allowed Sir Alexander Fleming to discover penicillin in a ruined lab sample. For similar reasons, Chinese researchers systematically reproduce experiments performed elsewhere in the world in the hope of discovering something scientists may have missed the first time around!” The researcher firmly rejects the idea of intellectualizing everything in an attempt to increase chances of success—experience and failure are part of the scientific process. “It’s a political and philosophical challenge,” Hillaire concludes. “We need to break away from the positivist view of the history of modernity, which tends to disregard failures instead of analyzing them.”

Yet the ACTE project does not involve building a museum devoted to innovation fiascos, such as the one opened in Tokyo by Kenichi Masuda to display his own personal collection. Exhibits include a strange plastic sheet which, placed in front of a black and white television screen, gives the impression of seeing the images in color. Not to mention a running toaster, literally speaking.

- 1. Marketed in France by France Télécom in the 1980s.

- 2. Launched by the Bic and Mr Pickle brands respectively.

- 3. Arts, créations, théories, esthétiques (CNRS / Université Paris-I Panthéon Sorbonne).

- 4. Archéologie des innovations abandonnées, délaissées ou résurgentes (CNRS / Université Paris-I Panthéon-Sorbonne).

- 5. According to the Quebec-based business newspaper.

- 6. See his article “L’Échec: Face Taboue de l’Innovation?” Lemonde.fr, November 19, 2014.

- 7. According to Paris Région Entreprise.

Explore more

Author

Science journalist, author of chilren's literature, and collections director for over 15 years, Charline Zeitoun is currently Sections editor at CNRS Lejournal/News. Her subjects of choice revolve around societal issues, especially when they interesect with other scientific disciplines. She was an editor at Science & Vie Junior and Ciel & Espace, then...