You are here

“Music Opens the Way to all Cultural Worlds”

In 2014, you created a research centre in Bayonne for world music (ARI) as well as the Haizebegi festival, which combines music and research. Can you tell us more about this festival?

Denis Laborde:1 In Basque, “haize begi” means “watch the wind.” Like the wind, music ignores borders, and bears witness. It says something about those who play it, and offers a wonderful gateway to many different worlds of culture. This festival, which we created with my doctoral students from the EHESS, is unique, in that it brings together the social sciences (conferences, debates, colloquia, publications) and music (concerts, films, exhibitions, dance).

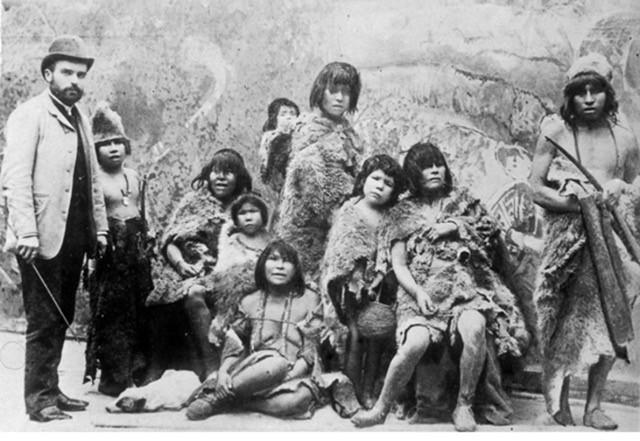

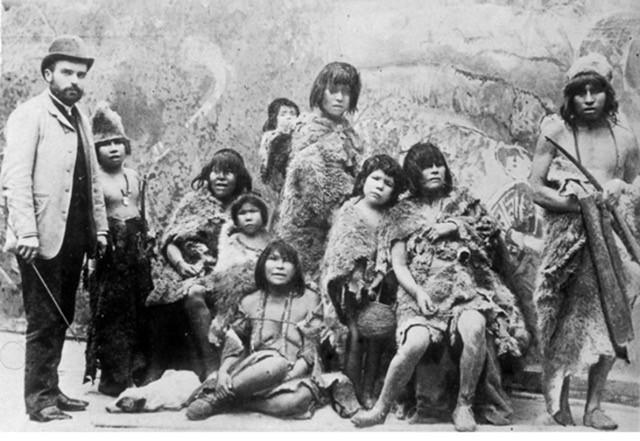

For this sixth edition, which was held in October, we welcomed Syrian, Cuban, Argentinian, and Kanak musicians as well as Basque creators, who had the place of honour with Rain of Music, an incredible opera for robots at the cutting-edge of technology, composed as part of an international scientific project.2 We also welcomed Selk’nam and Yagán peoples from the far south of Patagonia, thanks to the ethnomusicologist Lauriane Lemasson, who is devoting her dissertation to them. They have come from Ushuaia, Puerto Williams, and Cape Horn; their ancestors were exhibited in “human zoos“ during the Exposition Universelle of Paris in 1889, or sold at auction at Punta Arenas in 1895. To evoke this painful memory, on 12 October we organized a ceremony of resilience: Lars Christian Koch, who directs the Phonogramm-Archiv in Berlin, solemnly gave them sound recordings that were made between 1907 and 1923 by German ethnographic missions in Tierra del Fuego. It was a very symbolic way of giving their ancestors a voice once again.

The festival, as we conceive it, does not consider all music as an instrument of entertainment: it is a tool of intelligibility for human societies, which makes that art of listening into an attitude of knowledge that extends well beyond music. That is why a festival organized by researchers is not the same as a festival organized by cultural operators, if only because we combine it with a 332-page “programme” in the form of a scientific journal.

What exactly is the anthropology of music?

D. L.: It’s a specific way of understanding how “musical moments” are produced. It all began with curiosity, a libido sciendi (love of knowledge) and desire to preserve, which were accompanied by a providential tool: musical writing on a five-line staff. For a number of centuries, musical transcription helped “save” the music of others, as attested to by collections and songbooks. But when Thomas Edison invented his cylinder phonograph, it was sounds that were being conserved, as early as 1889. So what should be done with these rolls of wax? We established major sound archives for them in Vienna, Berlin, and Paris, with the Archives de la paroles, created by Ferdinand Brunot and Émile Pathé in 1911.

Studies on music from oral traditions thus developed in museums. It’s a way of preserving what we would today call the “world heritage of humanity.” Then ethnomusicologists began to ask intriguing questions: how were repertoires invented, stabilized, and diffused? How were they influenced? How should they be transcribed? What are their properties? How can they resonate with us? Spark new thoughts, emotions, moods? How do they put bodies in motion through dance or trance? We can also analyse how people gather, how they play music together, and reveal the cultural meanings that are attached to them, as well as the social life of those who play this music.

Does music have a universal dimension, or does its meaning vary based on the culture or the people?

D. L.: Music has this in common with language: it is a capacity of the human species. All human beings can speak and play music. Be that as it may, humans speak very different languages and play distinct types of music. Human capacities are “phylogenetically determined and culturally determinant,” in the words of Dan Sperber.3 That is the universalism of music. My dog Mugi tries to talk, and even to sing. I see that he’s making progress, but it doesn’t happen. I had to give up: he lacks a phylogenetic determination.

So to answer your question, yes, music has a universal dimension in that it is a shared capacity of the human species. For all that, being universalist does not mean that one wants to construct a general theory of music that would apply in all times and places. Each occasion for music is unique, and we study it as such. We then put all of the cases studied into different series, and see if we can generalize or not. But an eye for generalization only comes after in situ analyses, otherwise the view is biased.

Could you give us a specific example of a study that you are currently conducting?

D. L.: Since 2015, I have been interested in the musical practices of people who are in the situation of a forced migration. There is now a major influx of migrants to the Basque country. They cross the Iberian Peninsula and end up in Bayonne, where the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences of the CNRS has just set up our ARI Institute (Anthropological Research Institute on Music).4 This inflow has been remarkably handled by the city and volunteers working together in associations. It is important to point out that the Pausa centre welcomed 10,000 migrants in less than a year, in an extremely positive dynamic. As part of the institute, we are developing a program to understand what is at work when migrants play music in these places of respite.

For instance over the course of three months during the fall of 2015, the village of Baïgorry welcomed fifty migrants from Calais; at the end of winter, these migrants wanted to thank the village that they were about to leave. They asked for instruments, and were given a violin, a flute, drums, etc. This “intercultural celebration,” which will take place on 31 January, will be an astonishing moment for local inhabitants, as they will discover that these unclaimed individuals have traditions that can be shared. This radically changes the view one has of them. This is what is of interest to us, with support from the Institut Convergences Migrations, of which we are an integral part.

But we want to go further. While musical expression transforms the representations that we make of migrants, why not have researchers work with cultural institutions to make music an instrument of regained dignity, and even a tool integration? This is the central question in expanding the Collège de France’s Programme national d’aide à l’accueil en urgence des scientifiques en exil (Pause, National programme of aid and emergency welcome for scientists in exile)—with which we are associated—to also include artists. The expertise acquired in Bayonne shows that this aspect is quite substantial.

A good deal of your research is also about musical creation and improvisation.

D. L.: I find it fascinating! We associate traditional music with the identical repetition of patterns that “tradition” prevents one from leaving. Yet the opposite is true! The history of musical traditions is made up of moments where repertories are stabilized, followed by deviant gestures produced by inventive musicians. Most of these gestures go unnoticed, others cause controversy, yet others are implemented and lastingly change ways of doing things. This is how a tradition remains itself, all while changing over time. Improvisation is an extreme case. We tend to think that everything happens spontaneously, that you just have to give free rein to your inspiration. But you can’t improvise by improvising only yourself.

In La Mémoire de l’Instant,5 I showed that the Basque poets called bertsulari (verse makers) enjoy little success when they shut themselves away in their mental landscape. The best male and female improvisers—and today women are the champions—are those that communicate with the audience. They integrate its reactions in their improvisations, and each viewer feels like they have become a co-author.

You were a musician before shifting to research. How did you change directions?

D. L.: I studied at the Conservatoire national supérieur de musique in Paris, and so I grew up in this highly competitive world of scholarly Western music, in a world where you’re already too old by the age of 14! My last performance as a conductor was Alvin Curran’s Crystal Psalms at Radio France for New Albion Records, a firm based in San Francisco. Then came anthropology. I left behind the value judgments that I had integrated over the years, and the world became larger.

Since then, I have sought to include the creative capacities developed in artistic practice within scientific research. In my anthropology practice, I take inspiration from Bach, who conceived of musical composition through action. Bach was not a theorist, in that he never wrote a treatise on the fugue. But he composed The Art of Fugue, to which all treatises refer as a masterpiece of the human spirit. The Haizebegi festival is in keeping with this active approach.

I am among those who are trying to reinvent the profession of social science researcher. As a result, I am not working to construct a universal theory of music, but I make my engagement in the world an exemplum. So no, I no longer play the piano or compose, nor do I produce music. But that’s because we are in an emergency. Anthropology demands total engagement.

- 1. An ethnologist, CNRS Senior Researcher, and Director of Studies at the EHESS, Denis Laborde is a specialist on the anthropology of music.

- 2. This project establishes collaboration between artists from the University of the Basque Country (Bilbao), and computer scientists from Scrime (LaBRI, unité CNRS/Université de Bordeaux, Bordeaux INP) and Estia-Recherche in Bidart.

- 3. D. Sperber, Rethinking Symbolism, trans. Alice L. Morton, Cambridge, CUP, 1975.

- 4. Basque Anthropological Research Institute on Music, Emotion and Human Societies. Team from the Centre Georg Simmel (CNRS/EHESS unit).

- 5. La Mémoire et l’Instant. Les improvisations chantées du bertsulari basque, Donostia, Elkar, 2005, 349 p.