You are here

Music to Heal Memory

Could music have the extraordinary power to anchor itself deep in our memory and reactivate cognitive capacities we thought were lost forever? In care facilities for people with Alzheimer’s, it is common to see patients who cannot remember their own first name singing "Cheek to Cheek" and other songs learned in their younger days with unexpected vigor. Similarly, clinicians have long noted that certain stroke victims with aphasia (speech difficulties) were able to sing the words to their favorite songs without any speech problems and that patients with Parkinson’s disease were able to walk by synchronizing their steps to a musical rhythm or tempo. How to explain this phenomenon?

Sound is processed automatically by the brain

“When we hear music, our brain interprets it within 250 thousandths of a second—setting off during this short time a real neuronal ‘symphony,’” explains Emmanuel Bigand,1 professor of cognitive psychology at the University of Bourgogne and director of the LEAD.2 In concrete terms, sound is first of all processed by the auditory system, after which it passes through different areas of the brain involved in memory, emotions, movement (music invites us to tap our feet), language, and so on, as well as activating neuronal reward pathways (with the production of dopamine) when listening to music we enjoy.

Music is processed automatically by our brain at an unconscious level and is stored in our implicit memory. “Much of our musical knowledge and many of our musical representations (like structure), are acquired through natural exposure,” says Bigand. “Long before birth, babies memorize pieces of music which they are able to recognize one year after they are born without having heard them again in the meantime,” he continues. “At the other end of life, even when linguistic activities fade away, and particularly in the advanced stages of Alzheimer’s disease, music remains accessible. Not only does it impart a desire to communicate, smile and sing; it also reawakens the memories and events with which it is associated.”

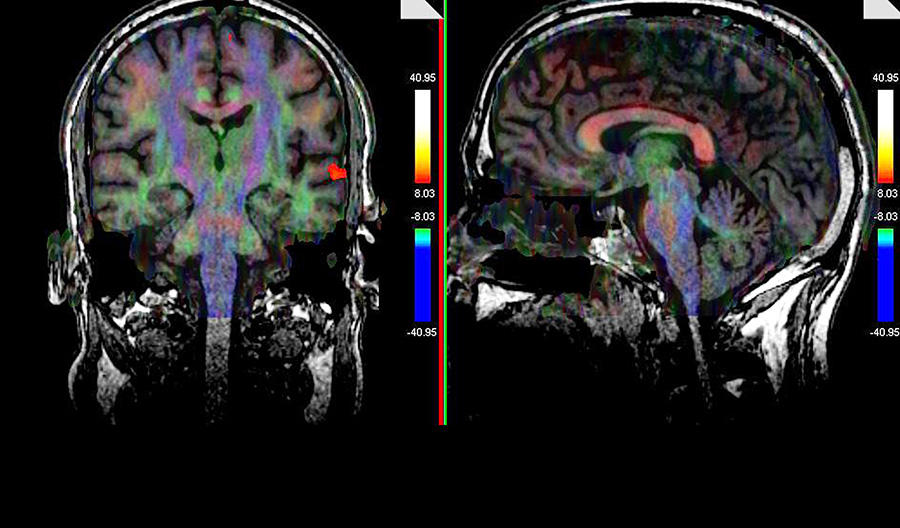

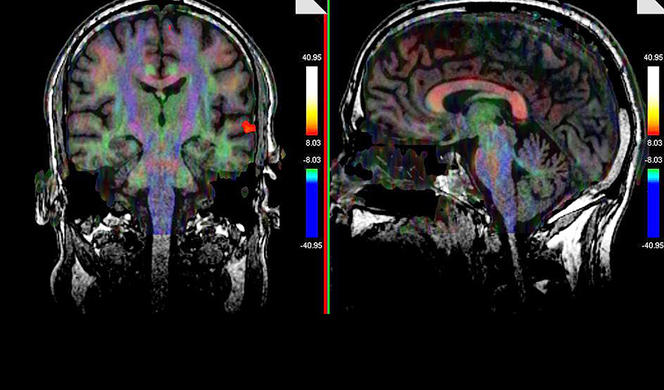

In the 1990s, Hervé Platel,3 professor of neuropsychology at the University of Caen, was one of the first researchers to observe the brain when it was exposed to music. Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), he identified the cerebral networks involved in musical perception and memory. Up to that point, the left brain was empirically considered to be the language region (particularly Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas) while the right brain was that of music, but things have turned out to be more complex.

Musical memory and words share regions of the left brain which allows us in particular to put a name to a musical work, while the right brain carries out perceptive analysis (recognition of a melody for instance). “This specific arrangement gives music memory an edge over the verbal one,” the researcher believes. “When a patient presents an injury to the left brain (language), the corresponding areas in the right brain do not normally compensate for this deficit. However, in most cases, the patient remains able to hear and memorize music (without necessarily being able to name it) and to derive pleasure from it.”

The astonishing persistence of musical memory in Alzheimer's patients

This persistence of musical memory is apparent particularly in Alzheimer’s patients, including in learning situations. Studies carried out by Platel’s research team in conjunction with Odile Letortu, a physician with the Alzheimer unit at the Les Pervenches retirement home (in Normandy), indeed show that patients (with moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease), seemingly unable to memorize any new information, successfully managed to learn new songs (containing a dozen lines) in under eight weeks (i.e., eight one-hour sessions). Even more surprisingly, some of them remembered and were able to sing the melodies four months after the end of the workshop.

These results led the researchers in Caen to repeat the experiment. They played the patients new musical vocal passages (poems and audiobooks) for eight days (one session daily). Once again, they noted that “the patients felt familiar with melodies that they had heard two and a half months earlier,” said the researcher. “Yet they no longer had any memory of the stories they had heard, thus confirming the extraordinary ability of music to leave a lasting imprint on the brain”.

A study in a group of 40 patients with Alzheimer’s disease (moderate to severe) and a group of 20 patients fitted with monitoring equipment is currently underway to identify the areas of the brain involved in the acquisition of new information. For Platel, who is coordinating the study with researcher Mathilde Groussard, “the key question is to determine whether this learning ability is associated with brain regions that still function or rather with an alternative memory circuit that takes over.”

Music against cerebral ageing

In any event, the demonstration of these astonishing abilities in patients with Alzheimer’s disease has led to the creation of new approaches for providing care. Some establishments for Alzheimer’s patients now offer systems based on familiarization, such as the use of a familiar vocal melody to help ritualize cleaning and dressing activities, or they may have output devices playing different types of music specific to individual activity rooms in order to help patients find their bearings in time and space.

Yet can we really talk about therapeutic effects? Many studies have shown that in the case of brain lesions, soliciting the areas of the brain involved in music processing has a positive effect on cognitive abilities (attention, memory, language processing) and promotes brain plasticity. “Repetition of musical stimuli favors exchange of information between the two sides of the brain and increases the number of neurons responsible for such communication, resulting in the modification of the actual structure of the brain. In musicians, identifiable signs of such change may be seen: in anatomical terms for instance, increased density of the corpus callosum (the network of fibers connecting the two sides of the brain) with regard to non-musicians,” notes Bigand.

In 2010, Platel and Groussard demonstrated for the first time the effect of playing music on memory. They noted that musicians have greater concentrations of neurons in the hippocampus, the brain region responsible for memory processing.

“This result confirms that playing music stimulates the neural circuits of memory and suggests that this activity could effectively counter the effects of cerebral ageing. Several studies have indeed shown that elderly subjects who have played an instrument for several years are at lower risk of developing neurodegenerative disease,” adds the researcher.

Benefits for all ages

Similarly, music has an effect on aphasia (the impaired ability to speak) which in the majority of cases result from cerebrovascular accidents. In 2008, the team of Teppo Sarkamo at the Brain Research Centre in Helsinki (Finland), demonstrated the effects of listening to music on the recovery of cognitive and emotional function in stroke victims.

Similar studies are currently underway at the Dijon University Hospital concerning the impact of early musical stimulation in stroke patients. “The initial findings show not only that patients experience pleasure in listening to music that brings back memories, but that they spontaneously begin to hum these melodies,” explains Bigand, who coordinates this research. “This reaction could facilitate the functional reorganization vital for the restoration of linguistic competence.”

Should we then all listen to music continually, sing or play a musical instrument to stimulate our brain in order to combat ageing? “There is no doubt,” the researchers answer in unison. “The benefits on the brain’s overall cognitive functioning may be seen at all ages, including in the elderly coming to music late in life,” says Bigand, who is campaigning for music to be taught from the earliest age, like sport.

Related topic:

Whatever Happened to Baby Dory?

- 1. Edited Le Cerveau mélomane , published in 2014 by éditions Belin.

- 2. Laboratoire d’études de l’apprentissage et du développement (CNRS / Université de Bourgogne).

- 3. Researcher at the laboratoire Neuropsychologie et imagerie de la mémoire (Inserm / EPHE / Unicaen) at the University of Caen. Joint author, along with Francis Eustache and Bernard Lechevalier, of Le Cerveau musicien , published in 2010 by De Boeck.

Explore more

Author

Carina Louart is a journalist and published author specialized in sustainable development, social issues and life sciences. She has authored several books including La Franc-maçonnerie au féminin, (Belfond publisher) Filles et garçons, la parité à petits pas ; La Planète en partage à petits pas ; C’est mathématique ! (publisher: Actes Sud Junior), which...