You are here

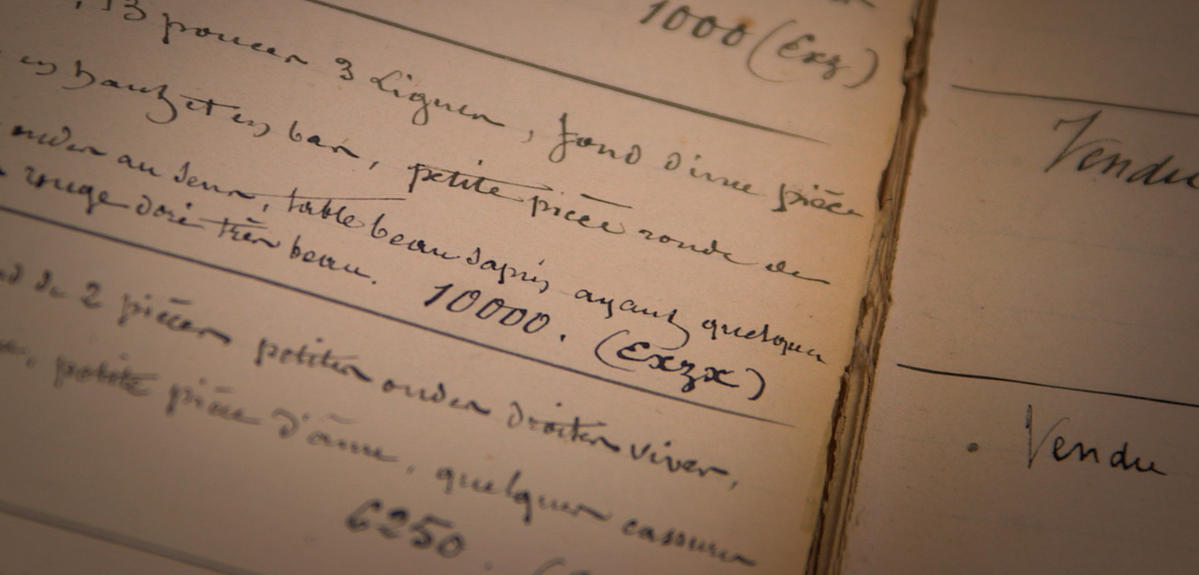

For over 200 years, a piece of musical history has remained hidden within these registers. Their aged yellow pages hold a well-kept secret: a column written in code. One curator at the Paris Museum of Music was intrigued enough to try to break it.

Jean-Philippe Echard – Curator

These registers were kept by the successors of Nicolas Lupot, an eminent luthier whose Parisian workshop was founded in 1795. After Lupot died in 1824, his work was successfully continued by a string of luthiers from the Gand, Bernadel, Carressa, and Francais families. These registers contain a century-and-a-half long history of their work.

For about a century, every transaction was written down within one of these registers. The sale of over 2,500 instruments, mostly violins, are recorded here. They were purchased by the luthiers and sold to musicians.

Jean-Philippe Echard

There are four individual prices listed for each instrument: the price the luthiers bought it for, the price they wished to sell it at, the actual price it sold for, and the reserve price, or the lowest price the luthiers were willing to negotiate down to.

But to keep some prices confidential, the luthiers carefully encoded them.

Jean-Philippe Echard

For instance this instrument was bought at a price which the luthiers noted in letters: “RXZ.” The price they wanted to sell it for was written in Arabic numerals: 800 Francs. Then here, in brackets, the reserve price is also in code: “NXZ.”

While hiding the price of a violin may have helped improve negotiations with clients, 200 years later, this is precious data for music historians.

Jean-Philippe Echard

By deciphering their secret code, we can lift the mystery around the luthiers’ practices, as well as the value of the instruments themselves. We can know their margins, commercial negotiation practices, and even the bargains they offered.

In order to break the code, Jean-Philippe Echard called on Pierrick Gaudry, a cryptographer at the Loria Research Unit. He had never worked on a 19th century code before.

Pierrick Gaudry – Cryptographer

At the time, telecommunications were growing. People realized that anyone could read their telegrams, so writing in code became somewhat fashionable.

Gaudry’s usual research requires computers and powerful calculators. His work: to improve the security of communication over the internet or credit card transactions, analyzing their core algorithms for weaknesses. But to break the code of the luthiers, he used a different set of tools entirely.

Pierrick Gaudry

A pencil and paper were all it took. There was no real need for elaborate digital tools.

Gaudry went through the pages of the register to familiarize himself with the code. It didn’t take long to form a hypothesis: the luthiers used a monoalphabetic cipher, replacing each number with a letter.

Pierrick Gaudry

Some letters of the code were obvious. We knew that 1 and 2 are most frequently found at the beginning of a number, so they were quick to figure out. H stood for 1, A for 2…

The rest of the deciphering process was more complex, but Gaudry was able to figure it out.

Pierrick Gaudry

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 correspond to the letters H, A, R, M, O, N, I, E, U, X. They spell out the word “Harmonieux,” French for “Harmonious.” At first the letters were scrambled, but suddenly it all made sense like in a game of Scrabble: “Harmonieux.”

Jean-Philippe Echard

The word “Harmonieux” is obviously related to music. In French, the name of the soundboard on a violin or cello, the instruments the luthiers worked on every day, is called a “table d’harmonie.” It was a very familiar word for these luthiers and it allowed the prices to be negotiated in a ‘harmonious’ way.

Now that the code is broken, the financial transactions of over 2,500 instruments have been revealed.

Jean-Philippe Echard

There’s so much data available to us now, it’s a 19th century version of big data, and it will help us understand the luthier trade.

It might even help us understand how some luthiers became international sensations.

Jean-Philippe Echard

There is a direct link between the price people were willing to pay for a violin and its reputation, or even the myth associated with a luthier from the past. For example, according to registers like these we’re able to see that Stradivarius was already breaking all records in the 19th century, because his instruments were the most expensive available.

One of the violins listed within the register is a part of the museum’s collection. This Stradivarius was bought by the Gand and Bernardel workshop for 4,000 Franks, then sold for twice as much in 1885. Its value is now estimated at several million Euros.

The Luthier and the Cryptographer

For over 200 years, a piece of musical history has remained hidden within registers of luthiers, string instrument specialists. These aged yellow pages hold a well-kept secret: a column written in code. One curator at the Paris Museum of Music was intrigued enough to try to break it.

Musée de la Musique, Cité de la musique - Philharmonie de Paris

Pierrick Gaudry

Laboratoire Lorrain de Recherche en Informatique et ses Applications (Loria)

CNRS / INRIA / Université de Lorraine