You are here

Long-standing consensus on the human origin of global warming

In March, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is due to present the Synthesis Report of its Sixth Assessment Report (AR6). This seems like a good time to look back at how understanding of climate change has developed and matured over the past few decades. It's a long story that goes right back to the nineteenth century, doesn't it?

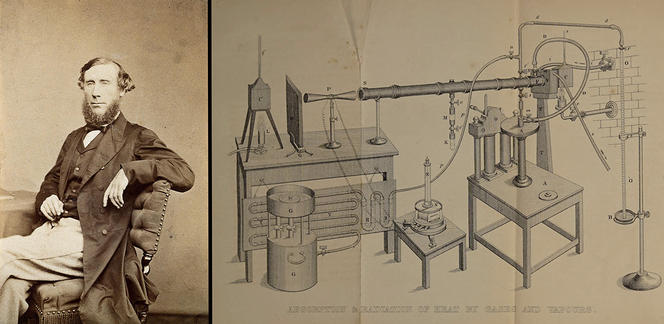

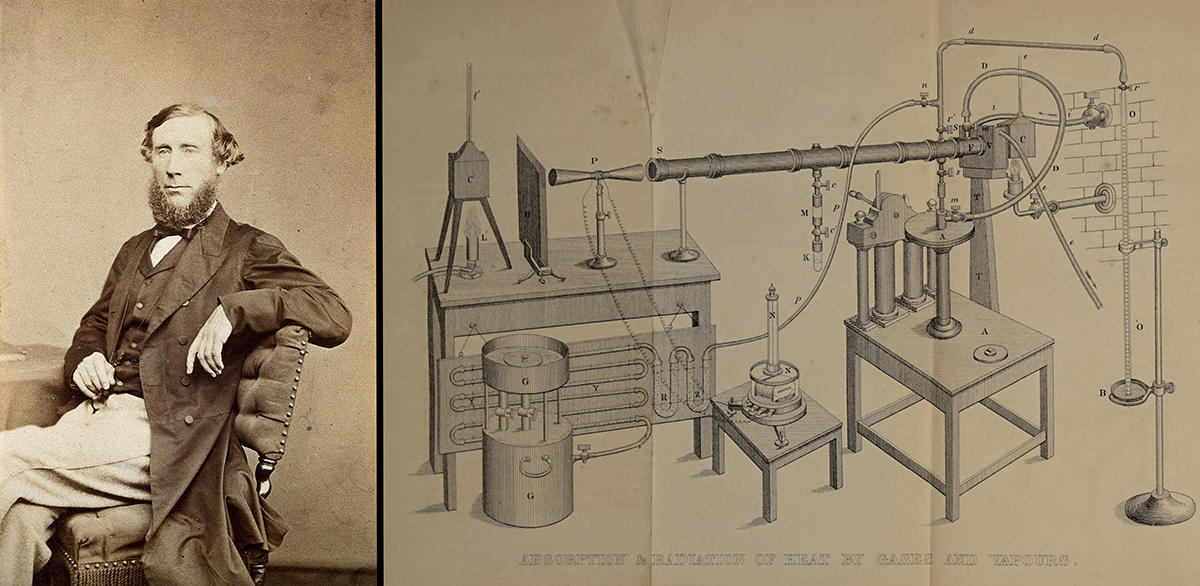

Hélène Guillemot1: Yes indeed. At that time, scientists like Joseph Fourier in France and John Tyndall in Britain laid the groundwork for an understanding of the atmospheric greenhouse effect. Then, in 1896, the Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius was the first to establish a connection between our emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) and the fact that they might lead to warming, for which he even provided a quantitative estimate. In fact, he quite welcomed this possible human-induced effect, since he believed higher temperatures might improve crop yields!

Yet a number of objections were raised against Arrhenius's warming hypothesis, which received little support. In 1938, the British engineer Guy Callendar thought he had detected the first signs of global warming, and put it down partly to CO2 emissions from industry. However, his findings were largely dismissed. Concern about a possible link between carbon dioxide from human activity and global warming nonetheless goes back a long way.

When did modern climate change science really get going?

H. G.: In the 1950s, in the context of the Cold War, the United States launched several scientific exploration and measurement campaigns worldwide.

Using new isotopic measurement techniques, scientists realised that contrary to what the opponents of Arrhenius had claimed, the ocean wasn't able to absorb all our emissions, and that the additional CO2 in the atmosphere could actually enhance the greenhouse effect. In 1958, the young American chemist and oceanographer Charles Keeling, funded by the International Geophysical Year,2 installed a detector at the top of the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii in order to measure the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. Ever since then, the Keeling Curve3 has confirmed the steadily rising concentrations of this greenhouse gas.

Subsequently, the post-war period, with the advent of the first computers in the United States, saw the development of the first numerical weather and climate models.

As a result, the idea that human activity might be causing global warming began to receive attention in the 1960s. In 1965, the report Restoring the Quality of Our Environment4 commissioned by the White House, included an annex on the possibility of climate change. The report suggested the use of geoengineering solutions to tackle it, although the prospect of reducing emissions wasn’t even mentioned!

When did this hypothesis begin to be taken seriously?

H. G.: It was a long, gradual process, but 1979 is often cited as a turning point. That year, the first World Climate Conference was held in Geneva and set up the World Climate Research Programme. This was also the year of the publication of the Charney Report5 commissioned by the American Academy of Sciences, in which the authors summarised the results of the five numerical models then in existence, and concluded: ‘If carbon dioxide continues to increase, the study group finds no reason to doubt that climate changes will result’. The report gave the first-ever estimate of the temperature rise for a doubling of atmospheric CO2, namely 3 °C plus or minus 1.5 °C, which is very close to the range accepted today. The document acknowledged that scientists were a long way from totally apprehending the processes at work (in particular, little was known about the role of clouds and the transfer of heat to the oceans), but despite the uncertainties, it was confident in its prediction of global warming, based on the convergence of climate models and on a sound physical understanding of the phenomena involved.

However, it was felt that there was no reason for alarm. It should be borne in mind that in the late 1970s, global warming had not yet been measured, since it was masked by the natural variability of the climate and the effect of aerosol pollution. And above all, attention was focused on other seemingly more urgent environmental issues such as chemical pollution, drought in the Sahel, and acid rain. Some scientists were even predicting that aerosols would have a cooling effect.

Nonetheless, wasn't it then that the world became aware of the problem?

H. G.: Yes, although this was thanks to a small number of scientists, such as the American climatologist James Hansen and the Swedish meteorologist Bert Bolin, who attempted to alert the political authorities, both in the US and worldwide. During the 1980s, several conferences organised under the aegis of the United Nations drew up the first scientific agreements and recommended setting up a group of experts to coordinate research on the climate. This led to the creation of the IPCC in 1988. Its role was to assess the available scientific, technical and socio-economic intelligence relevant to the issue of climate change, and to periodically provide a synthesis of this information to be agreed upon and approved by the representatives of the Member States.

When did it become clear that climate change was a reality?

H. G.: It all depends on what you mean by that. As we've seen, climate models had been predicting global warming since the 1970s. However, it wasn't until the 1980s that we had hard evidence for climate change, initially as a result of research into past climates. Ice cores from major drilling operations at the poles showed a clear correlation between the Earth's average temperature and carbon dioxide concentrations measured in air bubbles trapped in the ice for hundreds of thousands of years. It was in the 1990s that global warming actually began to be observed, and research showed that it could be attributed to human emissions.

Successive IPCC reports refined previous knowledge of climate processes and deemed human responsibility increasingly likely. The second report (1995) states that ‘the balance of evidence suggests that there is a discernible human influence on global climate’; the third (2001), that most of the warming since the mid-twentieth century is ‘likely’ to be attributable to rising anthropogenic concentrations of greenhouse gases; the fourth (in 2007, the year in which the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to the IPCC), that this increase is ‘very likely’ to be of anthropogenic origin, and the latest, in 2021, that human influence is ‘unequivocal’. In fact, for at least 15 years there has been an official consensus on the human responsibility for global warming, both among scientists and Governments, whose representatives endorse the ‘Summary for Policymakers’ of the IPCC reports.

And yet climate change denialist groups continue to cast doubt on the reality of climate change, hoping to hamper action to reduce humanity's footprint on the climate. Isn't that worrying?

H. G.: My impression is that in the past few years, the youth climate movement has prevailed over climate scepticism. It should first be noted that the IPCC has played an effective role in alerting and providing support for the climate negotiations at the COPs. Its reports informed both the Kyoto Protocol in 1997 and the 2015 Paris Agreement, which aims to limit warming to less than 2 °C above the temperature of the pre-industrial era.

As for climate sceptics, I don't believe we should take them too seriously. First of all, they don't represent many people and their influence is actually on the wane, according to the annual survey of the French Agency for Ecological Transition (ADEME). Moreover, focusing on climate deniers seems to me symptomatic of a somewhat naive way of understanding the role of science in the issue of global warming. As if having the right knowledge were enough to take the right action, and all we had to do to get society moving in the right direction was to eradicate the last pockets of climate scepticism that stand in the way of the dissemination of this information. In fact, tackling climate change and reducing CO2 emissions requires considerable changes across the planet, in every sector and at every level. And the challenges are far more varied and complex than the sole question of the robustness of scientific data and its release.

What do you believe are the areas of knowledge that need to be focused on?

H. G.: To answer that, it should be remembered that the IPCC is made up of three Working Groups. The first deals with the scientific aspects of the climate system and climate change. Working Group II is concerned with the effects of global warming, the vulnerability of socio-economic and natural systems, and how to adapt. Finally, Group III assesses solutions for limiting greenhouse gas emissions and mitigating its current impacts. Now that we know, thanks to Working Group I, that the Earth is definitely warming as a result of our emissions (even though knowledge on the climate still needs to be improved), the most significant issues have shifted to Working Groups II and III. This can be seen especially in the growing demand for regional studies of the effects of global heating. The latest report from Working Group II, released last year, now places greater emphasis on synergies and interdependence between climate, environment and society at the local level. In this field, the questions raised involve not only our understanding of the climate, but also a diverse group of disciplines, ranging from the hard sciences to the humanities and social sciences.

Is there less scientific consensus around the work of Groups II and III than concerning the conclusions of Group I?

H. G.: With Groups II and III, we're no longer talking about the same sciences as when we focus purely on the geophysical aspects of the climate. The ways in which evidence, uncertainty and consensus are established are no longer the same. For example, some of the chapters in Group III use so-called ‘integrated’ models, which include climate, technical and economic modules and produce socioeconomic pathways. To remain below 2 °C, such models rely on a number of technical solutions that remove carbon from the atmosphere on a large scale. However, there is no certainty that scientists will reach a consensus on the use of such techniques: some consider them to be untested, or to form part of a ‘technological solutionism’ that is highly controversial. In addition, these models are sometimes criticised because they are based exclusively on economic and technological criteria, and fail to take social realities sufficiently into account. For instance, they are not designed to consider the possibility of changes in production and consumption patterns. As soon as options for mitigating the climate crisis are discussed, the debates and arguments take a much more political turn.

Shouldn’t we stop expecting science to provide all the answers to global warming and its consequences?

H. G.: Climate scientists have always insisted that it isn't their job to tell us what to do. The decisions that must be taken to reduce emissions or adapt to climate change often require a high level of expertise – and we will still need the insight of science. But the choices to be made cannot solely depend on it. Planting trees to absorb CO2, or digging huge improvised reservoirs to combat drought, for example, are questions that require diverse and often specialised knowledge of plant ecosystems and the water cycle. They also entail taking into account local economies and populations, and making choices about political priorities, agricultural models, and so on. The IPCC will not be able to provide technological, economic or managerial solutions to which everybody can agree in order to carry out the change that will inevitably have to take place.

- 1. Hélène Guillemot is a researcher at the Centre Alexandre-Koyré / Histoire des Sciences et des Techniques (CNRS / EHESS / MNHN).

- 2. Period from 1 July 1957 to 31 December 1958, which coincided with maximum solar activity. Several dozen countries came together to conduct intensive research in fourteen different Earth science disciplines.

- 3. The graph of the accumulation of CO2 in the Earth’s atmosphere measured at the Mauna Loa Observatory from 1958 to the present day.

- 4. https://ozonedepletiontheory.info/Papers/Revelle1965AtmosphericCarbonDio...

- 5. https://geosci.uchicago.edu/~archer/warming_papers/charney.1979.report.pdf

Explore more

Author

Born in 1974, Mathieu Grousson is a scientific journalist based in France. He graduated the journalism school ESJ Lille and holds a PhD in physics.