You are here

Investigating climate sceptics’ disinformation strategy on Twitter

You recently published a study (in French) on the upsurge of activity by climate change sceptics that you have observed on the social networks since the summer of 2022. But first of all, what exactly is a climate change sceptic?

David Chavalarias1: Climate change sceptics, or denialists as they are also called, are people who reject the main conclusions of climate science and the IPCC reports reflecting the current state of knowledge about climate and climate change. In particular, they deny the fact that global warming is human-induced and that it will cause considerable harm. For some of them, there is no such thing as climate change, while for others, it is caused by the natural variability of the climate, meaning that we can do nothing about it. Some go so far as to say that an increase in CO2 is good for humans and the planet. They thus deploy a wide range of arguments aimed at delaying action to tackle the issue.

Your work focuses on those groups that have an agenda and an interest in promoting these ideas on social media. What can you tell us about them?

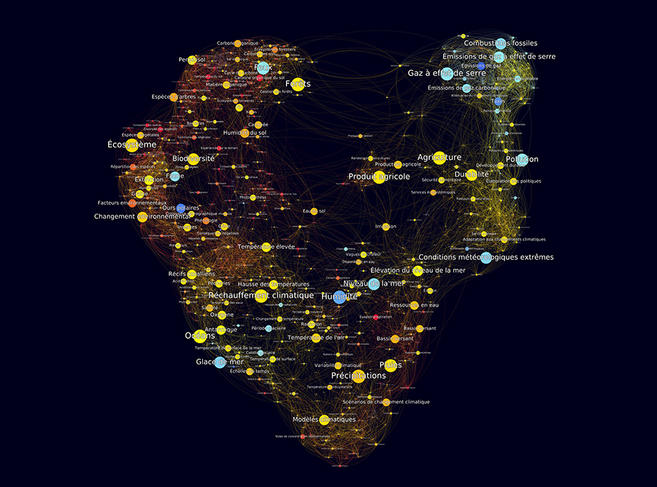

D. C.: In 2015, Maziyar Panahi and I set up an observatory called the Climatoscope, whose purpose is to analyse the worldwide climate debate on Twitter, in both French and English. The observatory collects hundreds of thousands of tweets on the subject every week. Together with our colleagues Paul Bouchaud and Victor Chomel, we study how this debate has developed over time, particularly during extreme weather events and international climate summits. We identify the forces involved and the strategies used by the different sides to get their messages across.

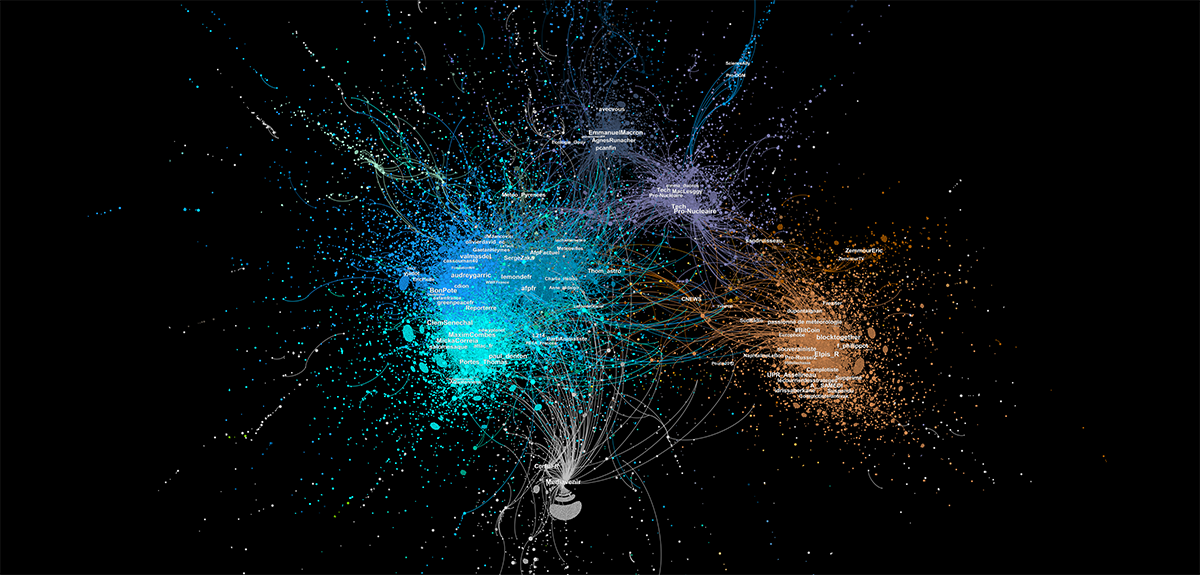

In the case of denialist groups, we were particularly interested in how they manage to persuade a significant proportion of the population to believe in pseudo-facts that run contrary to the scientific consensus and to people's perceived experience year after year. There is an element of communication warfare in all this, where a very minority group tries to impose its views, or at least sow doubt, among a growing part of the population. Since the summer, there has been a resurgence of climate-denialist activity in France from some 10,000 Twitter accounts, most of which belonged to the alt-right anti-vax and anti-system movement during the COVID pandemic and, to a lesser extent, to far-right groups such as Reconquête!

How do you investigate these accounts and their activity?

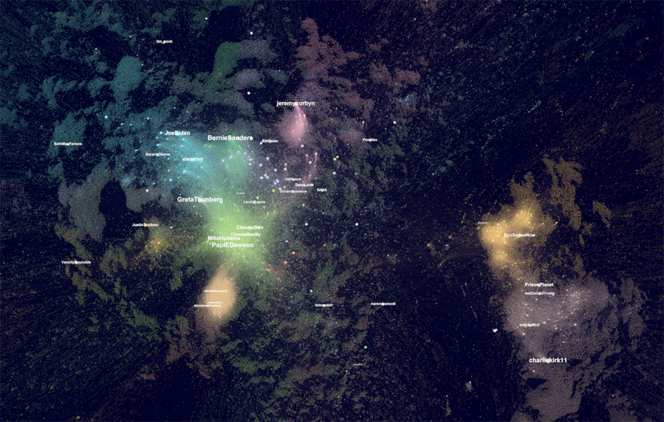

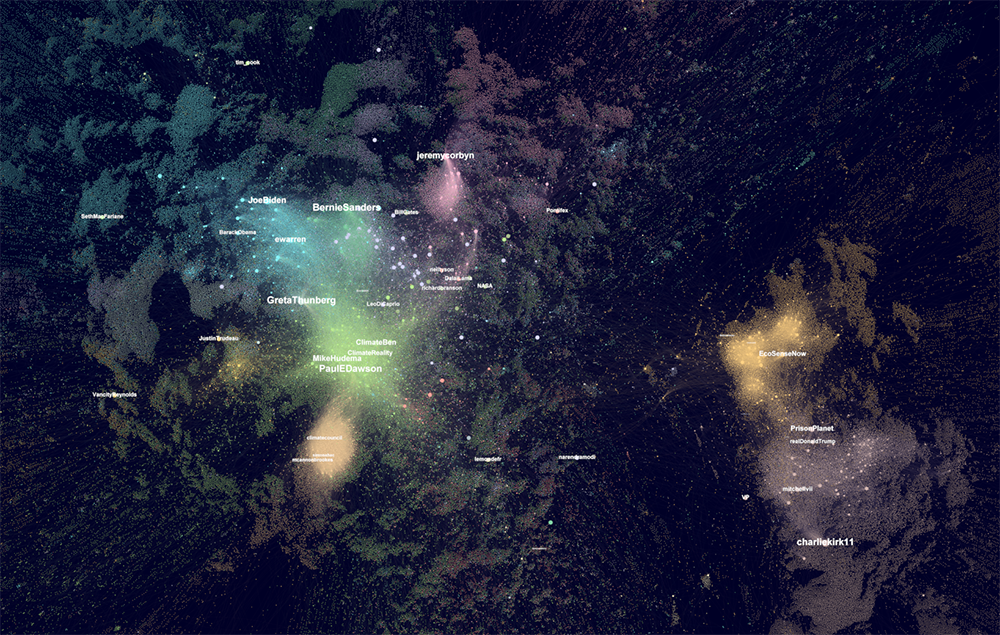

D. C.: Twitter was our preferred platform, firstly because it makes some of its data available to the general public, and secondly because it attracts a large number of influencers on political and climate issues. The tens of millions of tweets about climate change we've collected have content, authors, and information about such things as who answers whom, who likes what, and who's in touch with whom. This enables us to turn this data into a mathematical structure, a graph in which nodes represent users and the links between nodes correspond to their interactions. This graph helps us to characterise social structures in the form of communities of activists sharing the same ideology. We can then explore the content of what is being said. In doing so, we are trying to understand how these groups go about gaining influence and dominating their opponents.

What have you learned about these climate denialist groups, their strategies and their coordination?

D. C.: Their first characteristic is, of course, that they spread fake news and misrepresent genuine climate data. Secondly, they are far more active than those who defend the scientific consensus on climate change. They make up for being in a minority by a strong online presence. Another feature is that the climate denier ‘experts’ voice their opinions on all manner of topics. This is very different from those who defend the reality of climate change, who mainly stick to their field of expertise. Moreover, climate denialists are not afraid to contradict themselves. One day they'll say that climate change doesn't exist, and the next they'll spread the idea that it does exist but that nothing can be done about it. Climate sceptics also regularly engage in ad hominem attacks. They especially target IPCC scientists with the aim of stirring up controversy and delegitimising them. Denialists relay 3.5 times as many toxic messages as other communities.

Another of their features is that they have almost three times as many bogus accounts (bots or people paid to relay messages) than other groups. So it's highly likely that they engage in so-called astroturfing practices, whose purpose is to create a fictitious crowd that gives the impression that a cause has far more support from the population than it actually does. Finally, very specific patterns of activity can be observed. For example, for several Mondays in a row, they'll all start defending the idea that more CO2 is good for plants.

What arguments do they make?

D. C.: They use a whole range of different ones. For instance, they appeal to common sense, which is scientifically meaningless. Typical messsages can read: ‘It's snowing heavily in Switzerland and Austria, which has never happened before in mid-September. Luckily there's climate change.’ They also publish posts about the immorality of climate activists based on anecdotal facts such as human composting, as if to say, look, these people are insane. They put forward arguments based on conspiracy theories such as population control. For example: ‘Now that COVID is behind us, they'll use climate change to try and control us.’ They want to make it look as if the IPCC's work is driven by a political agenda, e.g. ‘The left wants to destroy the economy!’. In addition, they resort to pseudo-scientific arguments that focus on the tiny minority of researchers who are sceptical about climate change. Finally, many messages aim to disparage the expertise of IPCC members and their representatives.

How is this community organised?

D. C.: Worldwide, climate change sceptics fall into three main categories. First of all, you have the climate denialists, who are economically motivated. For example, fake activists are paid by the fossil fuel industries with the aim of delaying action against global warming. This has already been extensively documented. Then there are the political climate sceptics, who reject the reality of global warming and denigrate the measures proposed to address it, mainly to undermine the political opponents who support these initiatives. They are not necessarily interested in global warming as such. The US elections saw a resurgence of climate scepticism because it provided an opportunity to attack the Democrats' environmental agenda. And finally, a third category consists in geopolitical climate scepticism, originating in countries with totalitarian regimes. For these governments, such as the Kremlin, the climate crisis is a chance to divide populations and weaken democracies, as I explained in my book Toxic Data. For instance, we know that one of the strategies Putin uses to gain geopolitical influence is to carry out subversive operations on the social networks in a bid to weaken the democracies. His goal is to exacerbate internal divisions in order to alter social cohesion and ensure that the attention of governments is taken up by internal conflicts, or even, where possible, that these governments are themselves delegitimised.

The upsurge in climate change denialism that we've seen since the summer of 2022 appears to originate, in large part, in this third current. We've come across accounts that initially spread dissension about Covid-19 vaccines, before relaying the Kremlin's propaganda about the war in Ukraine, and eventually defending climate-sceptic theories. 60% of the climate-denialist community active in 2022 took part in pro-Putin digital campaigns. One of the strengths of these activists is that they have a political agenda but keep it secret. They attack anyone who puts forward scientific arguments and, playing on fear, tell people that this is an attempt to control them. These tricks are used in many subversive endeavours other than climate-denialism, especially by the American far-right and the Kremlin.

What is the impact of these climate-denialist groups?

D. C.: Climate change scepticism is gaining momentum, as shown by some opinion polls, and Twitter. And it's also having a real impact on scientists, who are harassed and denigrated, accused of serving the elites, and of having a political agenda. This is the ‘five D’s’ strategy, very popular with regimes like the Kremlin: Discredit, Distort, Divert, Dissuade, Divide. You can add a sixth: sow Doubt. These six D’s are now being applied in the context of global warming. Denialists distort the facts by saying that this phenomenon is caused by natural variation. They divert people's attention by accusing scientists who study climate change of serving a political agenda, and take every opportunity to discredit them. They use fear to dissuade governments from taking any serious action, by claiming that such measures would destroy jobs and the economy. They sow doubt by suggesting that the scientific consensus is weak or that the proposed initiatives will serve no purpose. All this is very effective provided that the targeted audience is unaware of this strategy. Hence the need for people to clearly understand what is really taking place online in order to avoid being manipulated.

Do you believe that government action to tackle climate change is being held back by this sort of climate-denialist cyberactivism?

D. C.: Although this is only my opinion, I am convinced that it is. You can see it in the case of renewable energy. As debate is raging on the social media around the idea that such energy is not efficient, some local authorities and the government are becoming more reluctant to go down this road. It is important to understand that it only takes 10% of the population adopting radical positions and taking to the streets to protest against such measures – or for example against increasing petrol prices – for governments to be less inclined to act. This is the divide and rule strategy: the more divided a country is, the harder it is to implement bold and effective public policies that address a major issue like climate change. In our study we show that, although the IPCC summaries drive the debate on Twitter in the medium term, on a day-to-day basis the reactions of climate denialists, as well as of people who believe in technological solutions to the problem, inhibit the online activity of IPCC members and of those who relay their conclusions. On the face of it, therefore, this type of climate-denialist activism hinders the dissemination of scientific knowledge and of the IPCC findings.

- 1. Senior researcher at the CNRS, and director of the ISC-PIF (Institut des Systèmes Complexes de Paris Île-de-France – CNRS).