You are here

The IPCC issues uncompromising conclusions on climate change

The Synthesis Report includes the conclusions of the three main parts of the IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report, published in 2021 and 2022, as well as four earlier Special Reports. That's quite a lot of information boiled down into just a few pages, isn't it?

Gerhard Krinner:1 It certainly is! We had to summarise all the reports, each of which is some 2 000 pages long, into a mere thirty pages. I decided to do a little bit of maths: in the entire IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, more than 70 000 scientific papers were cited. Given that on average one article is fifteen pages long, that makes a million pages of scientific literature condensed into thirty. It's dense stuff, highly concentrated!

How important is the Synthesis Report, in view of everything the IPCC has already published during its sixth assessment cycle?

G. K.: It marks the culmination of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. The Synthesis Report is the end product, the one that will form the basis for negotiations at future COPs. With this document, no Government can come to the negotiating table and pretend it doesn't believe that humans are responsible for climate change. Each country recognises and has approved every single sentence in the Report.

Can you tell us how you go about drafting this summary? Is there still debate among scientists at this stage?

G. K.: Initially, thirty of us were involved in writing the Synthesis Report, besides the Chair and Vice-Chairs of the IPCC and the Co-Chairs of Working Groups I, II and III (one of whom is Valérie Masson-Delmotte). I coordinated Section 2, which deals with long-term climate change, together with Kate Calvin, a US researcher who is NASA's Chief Scientist.

As for scientific debate, it takes place all the time. Science is never settled once and for all. There is always more to find out, and further details to discuss. However, on the fundamental questions there is no longer any reasonable doubt, especially about the causes of climate change. The first IPCC report, in 1990, noted that the changes observed were consistent with human activity, but also with the natural variability of the climate.

Since then, three more decades of climate change have passed. There has been a linear increase in global average temperature of almost 0.2 °C per decade since 1970. Today, the equivalent phrase in the IPCC report leaves no more room for doubt: human activity has caused warming of the same magnitude as that observed. Put another way, it is responsible for the whole of global warming.

The Synthesis Report has been approved by all the Member States of the United Nations. How does this procedure work?

G.K.: Once we, as scientists, have reached a consensus, we draw up a synthesis for policy-makers. This is a summary of what we want to tell them. The 195 countries then discuss the Synthesis Report and have to approve it sentence by sentence. Some may wish to remove a phrase, or on the contrary, emphasise a statement. Our role as researchers is to ensure that the final document remains scientifically correct. The negotiations are sometimes tough, but everything in the end report has the agreement of the scientists, who have an absolute right of veto to ensure that it contains no false statements.

Do the countries have to approve the report unanimously?

G. K.: Yes, but if one State doesn't agree with a sentence while the other 194 want it included in the report, the latter can still be approved, together with a statement to that effect. To my knowledge, this has never happened because it is very uncomfortable for a country to be pointed at it in this way.

Let's talk about the content of the Synthesis Report. What are its main conclusions?

G. K.: The first section of the Report focuses on the climate we see today and on how we got to this point. The key messages are: we are seeing change in every region of the world; it is unprecedented; it is extremely rapid compared to natural change; and it is caused by humans, full stop.

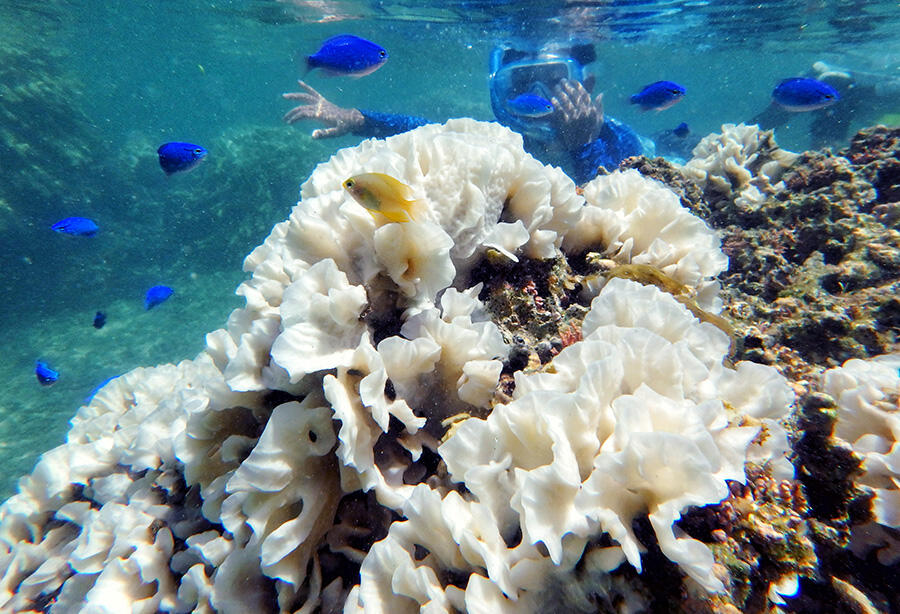

Action to halt climate change has started at a global level, and emissions are not increasing as fast as they used to. We are beginning to see some results. For example, the cost of renewable energy is falling and in some cases has already dropped below the fossil fuel benchmark. Although these signs are encouraging, they are far from sufficient. In some cases, the impacts of climate change are reaching the hard limits of adaptation. For instance, some ecosystems such as tropical coral reefs can no longer adapt because change is happening too fast or going too far.

Another key message is that it is the richest countries that are most accountable for climate change. And within each individual state, the wealthiest populations are the biggest emitters. When you look at the total amount of CO2 released from 1900 until now, it is clear that the former industrial countries bear a major responsibility.

What about the conclusions of the second section, which you coordinated?

G. K.: This second part addresses long-term climate change, beyond 2040. Taking into account the greenhouse gas reduction policies in place today, we are heading towards global warming in the range of 2.2 to 3.5 °C above pre-industrial levels – Editor’s note by 2100, with emissions stabilising at around the current level. That's not as disastrous as we might have expected 30 years ago. However, we can't rule out the possibility that releases will continue to rise. What we do know with greater certainty is that when we reach zero net CO2 emissions, the climate will stabilise rapidly. This is the clear take-home message from the summary.

What about the third section of the Synthesis Report?

G. K.: This part is about what we can do. It focuses less on the climate as such, and more on the action to be taken. In the medium term, i.e. over the next twenty years, the climate will continue to warm and it is very likely that at some time during the 2030s temperatures will exceed 1.5 °C as compared to pre-industrial times – Editor’s note. But that's no reason to give up. 2 °C warming is better than 2.5 °C, and 2.5 °C is better than 3 °C. Every little increase will have greater impacts, some of which will be irreversible.

With regard to climate action, one thing that needs to be done, of course, is to develop sources of renewable energy. However, we must also to take action on demand. Encouraging sobriety is not enough. We also have to make it possible. Especially since some measures aimed at reducing emissions have a positive effect in other areas such as air quality and food. Another conclusion is that any mitigation measures must take into account climate justice, because shifting the burden onto the world’s poorest populations is not the answer.

Some people believe that geoengineering could provide a solution to climate change. Did you consider this possibility?

G. K.: Geoengineering is briefly mentioned in the Synthesis Report, but not in the Summary for Policymakers. This is a complex debate because geoengineering involves very high risks. It won't return the climate to its previous state, because there are some regions where it might overcompensate for global warming, and others where it might not work very well. And there is a high probability of undesirable impacts such as alterations in precipitation patterns. In addition, there are unresolved issues concerning international governance. We also explain that we don't know enough about geoengineering and that more research is needed. In the current state of knowledge, it is clear that it cannot be recommended as a measure against climate change.

The end of the IPCC's sixth assessment cycle heralds the beginning of a seventh. How do you picture the next report? What issues will it have to address in greater detail?

G. K.: I believe that there will be further research on geoengineering and that in the seventh report we'll be able to talk about it in greater depth. We'll also improve our knowledge of adaptation measures, especially those that are most effective in the long term. We may be able to say more about carbon capture and storage. We'll also have a better understanding of climate change on regional scales, which is still difficult to model, and we may have the means to make decadal-scale climate predictions. There are plenty of areas in which science still needs to make progress.

As an IPCC researcher, don't you sometimes feel like a lone voice in the wilderness? You make extremely precise predictions about the future climate, and yet things don't seem to be moving forward much.

G. K.: Obviously it's frustrating to have to deal with delaying tactics and climate change denial. The climate denialist campaign on Twitter is highly irritating. But nonetheless, we are beginning to see a slowdown in the growth of carbon emissions. It's nothing like enough, but without the IPCC and everything it has done, things would probably be much worse. That's why the work of the IPCC, and especially of the entire research community working in this field, is of such vital importance for future generations.

- 1. CNRS researcher professor at the Institute of Environmental Geosciences (IGE – CNRS / IRD / INRAE / Université Grenoble Alpes).