You are here

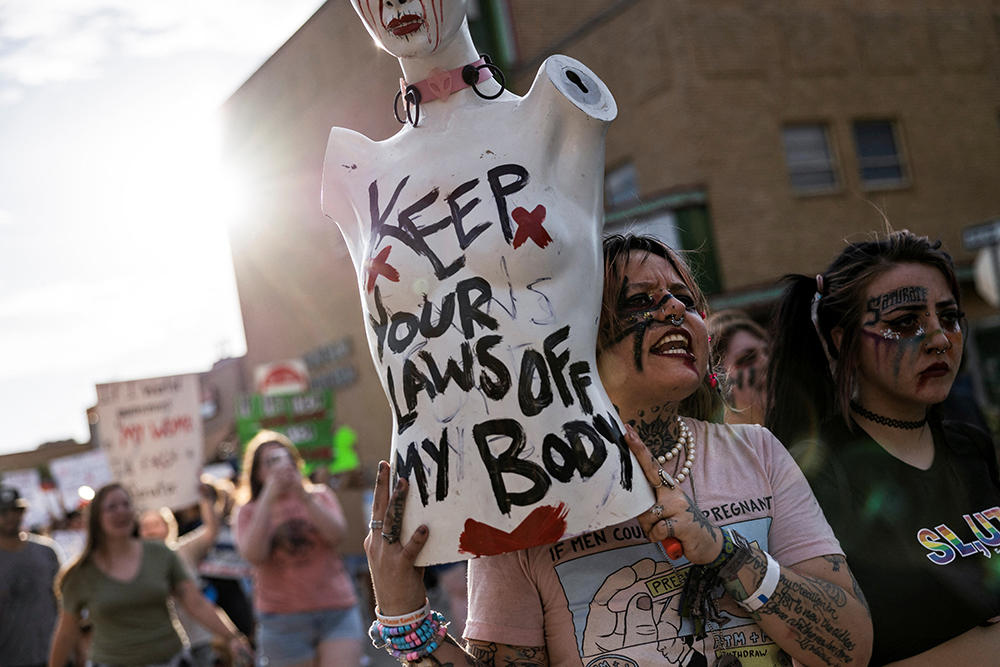

Feminicide: naming the crime in order to fight it

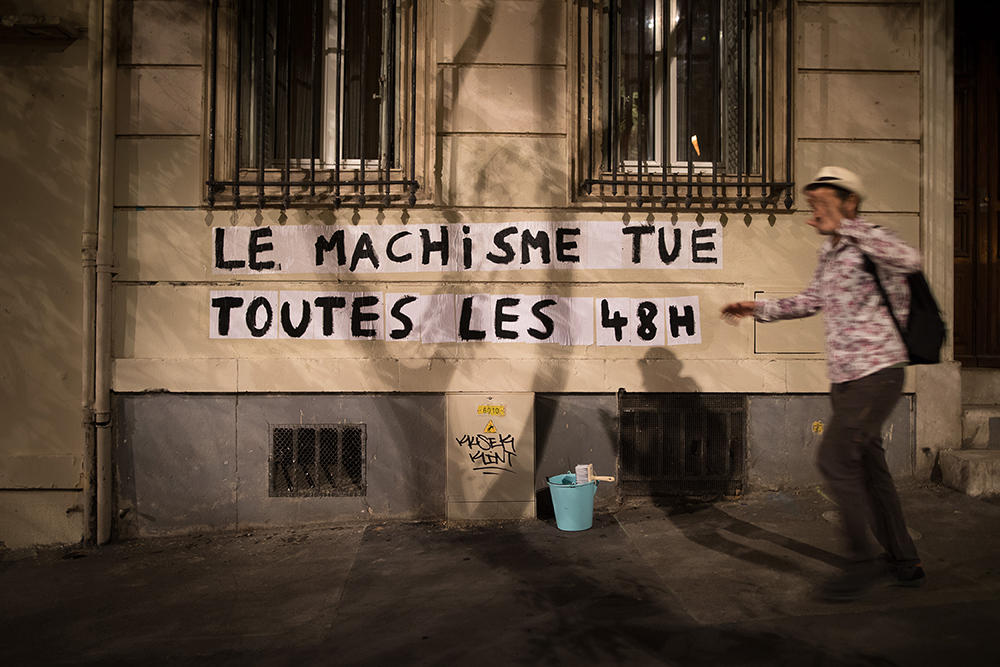

Every year the tally begins anew, with the grim statistic of the number of feminicides committed in a given country. In France, 122 women lost their lives in this way in 2021.1 In order to name the unspeakable, the term “feminicide” is widely used in today’s society. How did it enter the language? To answer that question, the historian Christelle Taraud,2 editor of the book Feminicides. Une Histoire Mondiale “Feminicides. A World History”, traces its etymology: “We need to look back to the 1970s, when women’s liberation movements took hold virtually everywhere in the Western world. At the time, as the South African-born American researcher Diana E. H. Russell explains, the murder of women because they are women, in particular by intimate partners, did not exist from a criminological point of view – it fell under a broader category, that of homicides. Russell asserted, however, that when a crime has no name it does not exist. A concept expressing this gender-specific crime therefore had to be formulated. To that end she coined the term ‘femicide’.” It was an important first step.

Femicide and feminicide

“The next step came in the early 1990s, when hundreds of bodies of murdered women were found buried in the Mexican city of Ciudad Juárez, near the US border,” the historian adds. These women were victims of sexual violence and mutilation, acts of hideous cruelty like burning with acid, pre- or post-mortem dismemberment… To come to grips with this atrocity, Latin American feminists and researchers joined forces, and the Mexican intellectual and political figure Marcela Lagarde y de los Ríos devised a new concept to designate the specific character of what was happening in Mexico: feminicide. “It’s an extension of femicide,” Taraud explains. “In this case it’s no longer the murder of a woman as an individual, but a mass crime, a State crime. It’s about killing women as an identity, as an entity, as a population.” The concepts of femicide and feminicide coexisted for several years in the Americas. But when they began to spread in Europe, especially after the #MeToo movement, things became more complicated…

“The usage is different from one country to another,” the researcher reports. “For example, the Norwegians only refer to ‘femicide’, and the French to ‘feminicide’ – albeit in a highly reductionist version: every femicide is considered a feminicide. This is problematic because it does not involve any real understanding of the etymology of these words and the contexts in which they emerged. Furthermore, the notion of feminicide was established to designate a mass crime, a State crime – a connotation that is totally absent in our reinterpretation…”

Although French society has embraced the term, which Taraud commends despite the shortcomings, the reality of feminicide is more complex, and a source of debate among specialists.

A system of feminine oppression: the feminicidal continuum

According to Taraud, the terms “femicide” and “feminicide” are nonetheless not entirely suited for describing the situation: “We must understand that violence against women is part of a continuum – a system for the oppression, control and domination of females that ultimately leads to femicide and feminicide. In society, the groundwork for the actual murder is laid by a whole array of rhetoric, mechanisms and institutions…”

In this sense, the feminicidal continuum encompasses all the violence and aggressions inflicted upon women from cradle to grave, in more or less subtle forms and varying from society to society. One could mention, among others, linguistic differences in some languages (e.g. the French grammar rule that the masculine gender prevails over the feminine), in education, in political and religious systems, along with economic discrimination, sexist jokes, sexual harassment in the public space, insults, beatings, physical and sexual mutilations, child marriage, forced marriage, forced maternity, forced abortion and sterilisation, female foeticide and infanticide, the imposition of heterosexuality, lesbophobia, sexual slavery, sexual abuse and crime, rape, murder… Building on the concepts of the “sexual violence continuum” and the “gender violence continuum” formulated by the British sociologist Liz Kelly in the late 1980s, Taraud proposes the term “feminicidal continuum” to describe the phenomenon.

“It’s a cycle that seeks to perpetuate patriarchal systems over the very long term, based on a binary principle: the superiority of one group and the inferiority of another,” she explains. “Such systems emerged quite early on, but not always with the same traits.” Male domination arose in the Neolithic Age, with sedentarisation and the domestication of animals and plants. According to the Argentine-Brazilian anthropologist Rita Laura Segato, the process began with low-intensity patriarchal systems relying on a dual matrix, in which women and men had complementary roles – even though the latter had certain privileges.

“Then came the formation of high-intensity patriarchies with a hegemonic tendency,” Taraud says. “They are founded on a binary matrix, invalidating everything associated with the female gender. Originating primarily in the Western world, the phenomenon started with the establishment of the Roman Empire and has never stopped gaining momentum. The closer we come to the modern age, the more radicalised the patriarchal systems become…” In Europe, beginning in the 15th century, this misogyny has been reflected in episodes of violence – not only individual, but collective as well. Taraud mentions the case of the witch hunts, whose goal was to eradicate large portions of Europe’s female population while subjugating the rest.

How does the French justice system name these types of violence?

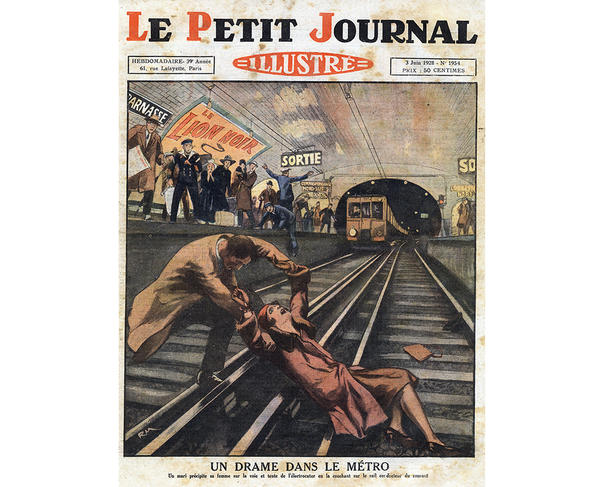

In France, terms to denote gender violence, like “feminicide”, do not feature in the Criminal Code. “They can be used for the social identification of a crime, but have no legal value,” explains the legal historian Victoria Vanneau.3 In her view, this omission does not prevent the justice system from punishing violence against women. She points out that the courts began addressing these questions starting in the 19th century, even though the terminology used was different.

“In my analyses of the legal archives from the 19th century, I found no mention of ‘domestic violence’,” she reports. “On the other hand, I did find murders and cases of grievous bodily harm. I actually came across the whole taxonomy of penal infractions, which were recognised and applied to husbands who had killed or battered their wives, and vice versa. When the Criminal Code was being drafted, in 1800-1801, the authors considered including the expression ‘conjugicide’ as an aggravating circumstance.”

The idea was ultimately rejected. However, Vanneau points out that the treatment of violence against women evolved over the years, reflecting increased awareness by the justice system. “Judges paid ever-closer attention to it in an effort to qualify it, showing a willingness to interpret and adapt the law according to the case. They discerned patterns of habitus, continuities in the violence.”

Vanneau also notes that in the 19th century, juries were comprised of men, from the middle and upper classes, who felt that the legal system should not interfere in couples’ private lives. “In this context,” she says, “it was not easy to reach a majority in favour of convicting a husband who had abused his wife. Instead, the judges often practiced what in France is called ‘correctionalisation’. In other words, by reducing the charges, they managed to convict men who would no doubt have been acquitted, had their crime been qualified as murder.”

Backed by a number of feminist activists, the proposal to introduce the term “feminicide” in the Criminal Code has been the subject of much debate in recent years. Vanneau is not in favour of this initiative: “The Criminal Code is very well conceived, allowing for all aggravating circumstances. Incorporating feminicide would be counterproductive. It’s not a legally viable term. There is no general consensus on the actual meaning of ‘feminicide’. Adopting this terminology could spawn endless different interpretations, resulting in disparities depending on the time and place.”

Taraud, on the other hand, believes the legal recognition of feminicide is essential: “Of course, a case of feminicide can always be handled as a homicide. But its specific nature must be established. If the justice system doesn’t acknowledge feminicide as such, it euphemises the crime in a sense. This sends out the wrong message to society. I don’t understand why this is still debated now that so many countries have already passed laws thereupon without encountering any particular problems. In Latin America, for example, 18 countries, including Brazil, Costa Rica, Chile, Guatemala, Mexico and Colombia have made feminicide part of the law.4 Despite the objections, I think we will reach that point in France. History is heading in that direction.”

Putting an end to an eternity of violence

Other than law enforcement, what are the solutions that could help stop the violence? “First on the list is knowledge,” Taraud says. “What is presented as objective knowledge is in fact highly subjective: there is no neutrality or objectivity in the way human history has been told. We must therefore realise that we are facing a genuine disaster on a global scale.” The historian points out that the phenomenon is not limited to the hundreds of feminicides by intimate partners reported each year in the EU countries. For example, 200 million women around the world have been sexually mutilated, and 200 million girls in Asia have been killed in the womb or shortly after birth since the 1950s, due to mass foeticide in India and female infanticide policies in China.

Both researchers call for a basic change of paradigm. Taraud denounces the violence that underpins the patriarchal system. “We need to rethink our relations with the regimes of power, of coercion,” she emphasises. “A truly human society is a non-violent society.” Vanneau is of the same opinion: “When we look at the make-up of our society, the values upheld by governments, and even by the sports world – all of them are performance-oriented… Those are masculine values. It is an entire system that needs changing.” The two specialists also highlight the importance of prevention and education: “When people are taught hatred for others from early childhood, no matter what form it takes, chances are they will reproduce that attitude later,” Taraud points out. And according to Vanneau, “There are forms of education in male-female relations that need to be improved at all levels of society, from the working class to the most affluent.”

The reinforced sorority described by Rita Laura Segato and Aminata Traoré in the book edited by Christelle Taraud will be another powerful tool. It calls for an effort that rejects hierarchical structures embodied by individuals in favour of horizontal, collegial structures that can act as networks – local, regional, continental, and (why not?) global.

- 1. https://www.vie-publique.fr/en-bref/286154-augmentation-des-feminicides-...

- 2. A historian specialising in issues of gender and sexuality in colonial contexts, Christelle Taraud is a professor in the Paris programmes of Columbia University and New York University. She is also an associate member of the 19th-Century History Center (Paris I Panthéon-Sorbonne and Sorbonne Université).

- 3. A doctor of law and a CNRS research engineer at the ISP institute for social and political sciences (CNRS / ENS Paris-Saclay / Université Paris Nanterre), Victoria Vanneau has taught institutional history at Université Paris-II, Université Rennes-2 and Université d’Angers. She is a member of the IERDJ institute for studies and research in law and justice.

- 4. Le féminicide, parlons-en ! #LeFeminicideDansLaLoi — ONU Femmes France