You are here

A nose for smell disorders

In humans, smell is often – wrongly – considered as a secondary sense. It is nevertheless omnipresent. “Each time we breathe in, we sample odorant molecules in the environment that enable us to detect the presence of objects that may be of value in terms of our protection, our diet or our relationships with others”, explains Moustafa Bensafi, CNRS research professor within the Neuropop team of the Lyon Neuroscience Research Centre (CNRL)1. “A sense of smell allows us to detect smoke, stale food or even the presence of an animal that might be dangerous or familiar. It is also characterised by a very strong affective and emotional component.”

50 shades of olfactory disorders

Essential to our safety and pleasure, our sense of smell can malfunction. The percentage of people presenting olfactory disorders has been evaluated at between 5% and 20% worldwide, depending on the surveys and countries. In France, a 2015 CNRS study led by Bensafi involving more than 4000 participants revealed that around 10% of the population – or more than 6 million people! – may suffer from an olfactory deficit. The symptoms and causes of these disorders can vary considerably.

“The term ‘olfactory deficit’ is quite generic insofar as it covers both quantitative and qualitative changes to the sense of smell,” the scientist notes. “At a quantitative level, it may reveal a total loss, called anosmia, or a partial loss, referred to as hyposmia (a normal state being called normosmia)”. Cases of hyperosmia, or enhanced sensitivity to smells, are much less frequent. “There may also be qualitative changes. For example, a person may perceive a smell of roast chicken when in fact they have been exposed to peanuts, a disorder called parosmia”. When the latter is associated with an unpleasant emotional perception, it is referred to as cacosmia. Finally, it is possible to perceive “phantom” odours that are often unpleasant but do not result from any external stimulus, a condition called phantosmia. But once these disorders have been identified, it is crucial to understand what triggered them if they are to be treated.

The role of infections

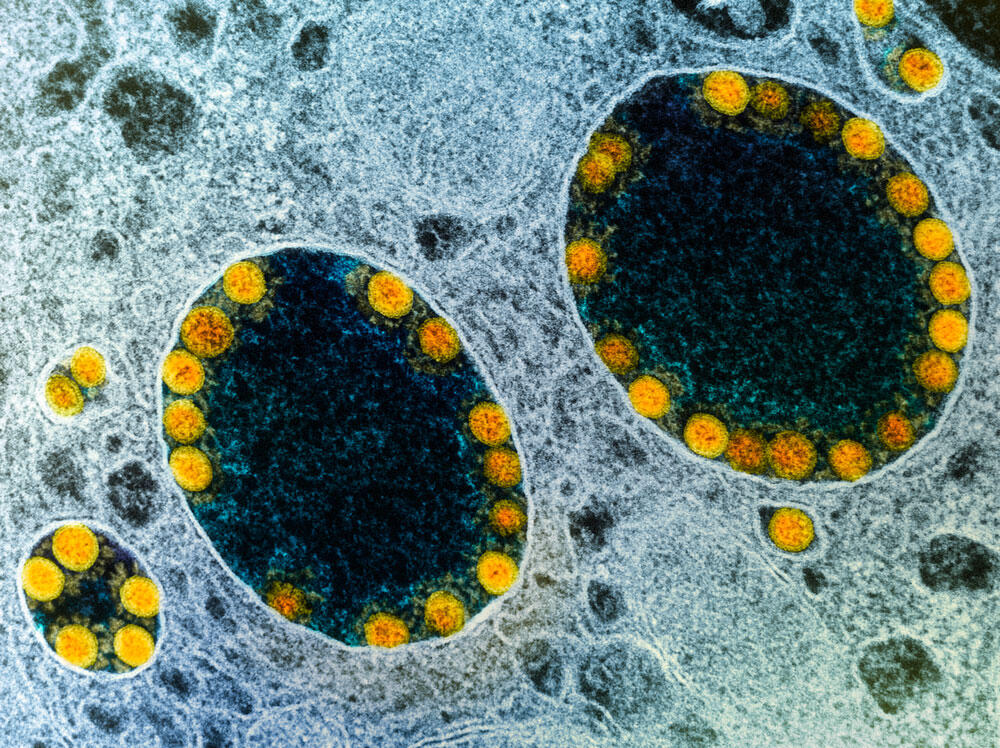

Although cranial trauma is an obvious cause of anosmia, notably because of lesions affecting the olfactory nerve that connects the nose to the brain, the Covid-19 pandemic evidenced the role that viral infections could play in the onset of olfactory disorders. Several hypotheses have been put forward to explain the impact of infection by SARS-CoV-2 on the olfactory system. The first hypothesis is that the infection causes inflammation and oedema, which prevents the air from reaching the olfactory epithelium in the upper part of the nasal cavity. This is indeed what happens during other ENT problems affecting the nasal cavity (polyps, chronic sinusitis, etc.) that can cause olfactory disorders.

Another possibility is that the virus directly attacks the olfactory cells. “There are three families of cells in the olfactory epithelium: olfactory receptor neurons, basal cells that guarantee renewal of the neurons, and support cells that ensure correct neuronal functioning,” notes Bensafi. “The virus may bind to the support and/or basal cells and thus indirectly affect the neurons.” Finally, a few studies have suggested that the virus may infect the olfactory bulb in the brain, although these different hypotheses are not mutually exclusive, the researcher points out.

Cancer, Alzheimer’s and metabolic disorders

Several non-infectious diseases may also be implicated in the aetiology of olfactory disorders. This is the case for certain cancers, either directly because of the condition or due to the adverse effects of chemotherapies that inhibit the renewal of olfactory neurons.

Profound olfactory deficits are also observed in the context of Alzheimer’s disease. Indeed, 80% of these patients suffer from an olfactory disorder, which thus constitutes an early signal of the pathology. “In the case of Alzheimer’s, it is thought that the cerebral zones situated in the ventral region of the brain (the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex and olfactory cortex) are affected,” explains Bensafi.

More recently, correlations between diabetes, obesity and olfactory disorders have been demonstrated. “By studying the interactions between olfaction and the regulation of energy metabolism, we discovered a new nerve circuit linking the cerebral olfactory system and the pancreas that is able to regulate the amount of insulin released into the blood,” explains Hirac Gurden, a neuroscientist and CNRS research professor in the Unit of Functional and Adaptative Biology (BFA)2. “We thus know that a person who develops obesity or diabetes has a high risk of developing anosmia.”

It is known that in obesity, an accumulation of adipose tissue causes metabolic distress that manifests itself in the form of numerous dysfunctions affecting the liver, intestine and pancreas, as well as the brain. An excessive consumption of very fatty, very sweet or very salty foods can therefore result in distress to brain tissues, and especially the olfactory system.

The effects of depression and ageing

“Hedonic value is an essential dimension of odour perception,” confirms Nathalie Mandairon, CNRS research professor at the CRNL and director of the GDR O33. “If you ask people to smell an odour, their first reaction – even before trying to identify it – is to say ‘I like it’ or ‘I don’t like it’. We have focused on what encodes this hedonic value in the brain, and discovered that this occurs as early as the first cortical relay of olfactory information, the olfactory bulb. We have also shown that pleasant odours give rise to motivated behaviour, to approaching the smell, which calls on the reward circuit.”

The scientist and her team have also demonstrated the effect of early stress on odour perception. Indeed, trauma in early childhood frequently induces depression during adulthood, and depression is frequently associated with disturbances to odour perception which, in return, tend to worsen the symptoms of anxiety.

“In mice, we have observed that young specimens mistreated by their mothers develop anhedonia (loss of ability to experience pleasure – Editor’s note), which is characteristic of depressive syndrome. And these young also display changes to the perception of pleasant odours, which are identified as unpleasant,” explains Nathalie Mandairon. “Working in collaboration with Dr Jérôme Bruneli, we are currently exploring the neural bases for these alterations in animals and humans.”

Ageing can also be responsible for an olfactory dysfunction called presbyosmia. Mandairon has thus studied the effect of age on the perception of pleasant odours. In many cases, elderly people modify their diet because their sensation of enjoyable smells has changed – while that of unpleasant ones remains roughly the same. “As mice become older, an increasing number of agreeable odours become displeasing and are explored less and less. This modification during ageing is linked to a defective recruitment of the reward circuit”, explains the scientist. This discovery could enable a clearer understanding, and the prevention of, undernourishment in the elderly.

Major impact on daily life

The loss of food pleasure and undernourishment are far from being the only consequences of olfactory deficit, which, according to a biomedical definition, are “sensory handicaps”. “They constitute a change to or loss of a sense, olfaction, that can protect us and participate in our well-being and pleasure. If this sense disappears, we are in a constant state of insecurity, and in numerous ways,” explains Gurden. In fact, deprived of this detector of danger, anosmic individuals may suffer from serious domestic or health accidents. Some may allow their home to catch fire because they have forgotten something on the stove and could not detect the smell of burning; while others may become ill from food poisoning because they could not smell the odour of stale food.

Furthermore, explains the scientist, “a sense of smell plays a major role in intimacy with our partners. It is also crucial to sensory exchanges between parents and children. During the first four months of life, a baby has blurred vision and their social interactions are in many cases of an olfactory type. In other words, during these four months, newborns are olfactory individuals and it is odours that guide their life”.

A sense of smell thus participates in our well-being and mental equilibrium. It is therefore not surprising that olfactory disorders affect mental health and social interactions. “When the sense of smell is impaired, relationships with others are disturbed. A person no longer has control over their body odour. They may wear too much perfume or none at all, take too many showers or not enough. This is a source of anxiety and stress,” insists Bensafi. Self-esteem is impacted and social withdrawal is common, frequently involving absence from work and isolation from family and friends; such reclusion is all the greater when the taste of foods disappears and people eat alone.

Re-educating our sense of smell

Olfactory rehabilitation is now widely employed. It is designed for all people who suffer from smell disorders, whether they are caused by viral infections, cranial trauma or natural ageing. “Recovery rate has been estimated at 80% among individuals who start rehabilitation and pursue it for at least three months without any interruption,” explains Gurden. The protocol is based on the use of four essential oils: rose, lemon, clove and eucalyptus, which enable maximum stimulation of the different families of olfactory receptors. Over a period of at least three months, blindfolded patients must “sniff” the four odours on a daily basis: the aim is to spark olfactory attention and restore the link between the nose and the brain.

As a second stage, the name of the essential oil should be read while it is being sniffed, in order to trigger olfactory memory. “It is crucial to inform the patient that this training is based on the idea that stimulating the olfactory system repeatedly, every day, can accelerate recuperation,” notes Bensafi.

Within Anosmie.org, the French association for patients suffering from smell disorders, Gurden and his team have developed an online app (https://covidanosmie.fr/), a sort of “electronic coach” for smartphones so that people can visualise their progress. The protocol does not always work. In this case, rehabilitation will exploit the fact that foods can also be perceived by the gustatory system and trigeminal system (composed of the trigeminal nerve that divides into three branches in the mouth, nose and eyes – Editor’s note), which is sensitive to spices, tingling, freshness and several volatile compounds.

“We strive to help patients realise that they can rebuild their odour libraries by calling on other sensory systems,” explains Bensafi. “By encouraging sufferers to cook, and inviting them to ‘keep their nose over the pot’, they can recover olfactory competence in a natural manner and thus fight against social isolation.”

Treating olfactory disorders

Other than surgical procedures such as polypectomy (the removal of polyps obstructing the nasal fossa), medicinal treatments based on corticosteroids and/or antihistamines in a nasal spray can improve olfaction in patients suffering from inflammatory nasal disorders.

A promising therapeutic option is currently being developed in the context of the European research project called Rose (Restoring Odorant Detection and Recognition in Smell Deficit): the development of an “artificial nose”, an olfactory prosthesis that can restore odour perception in anosmic patients. “This international consortium is combining the expertise of seven European laboratories and the French company, Aryballe Technologies, in order to design this new device,” says Bensafi, who is coordinating the project. “The initial results are encouraging and allow us to hope that we will obtain a first proof of concept within the next two to five years.”

However, this solution is unlikely to become available to patients for another ten years or so, but it raises hopes for all those whose anosmia does not respond to traditional treatments. It also opens the way towards new scientific and technological possibilities regarding the miniaturisation of affinity sensors, which are useful for other applications such as the quality control of foods, aromas and perfumes. ♦

Read more

Sentir. Comment les odeurs agissent sur notre cerveau (in French), Hirac Gurden, Les Arènes, 2024, 256 p.

See on our website

https://news.cnrs.fr/opinions/how-to-improve-care-for-anosmia-patients

Claire de March, a researcher with flair