You are here

The Tyranny of Appearance

(This article was published in CNRS Le Journal n° 222-223, July-August 2008.)

It does not take a rocket scientist to realize that our modern-day Western society glorifies physical appearance—hard to believe that for centuries, the body was more or less hidden, oppressed, dismissed as a mere shell waiting only to return to the proverbial ashes and dust. “Whereas the ancient Greeks celebrated the athletic, healthy, slender body, medieval Europe, under the influence of the Christian promise of a better life after death, focused on the salvation of the soul and saw the body as a fleeting receptacle, suffering all the ills that afflict humanity (famine, war, epidemics…), as a ‘theological object,’ a divine creation that must not be violated, or dissected,” explains Gilles Boëtsch, director of the ESS1 laboratory. “In the Middle Ages, the body was seen as a simple inevitability,” adds Bernard Andrieu of the ADES,2 “something to be endured, like slaves their masters.”

The Renaissance of the body

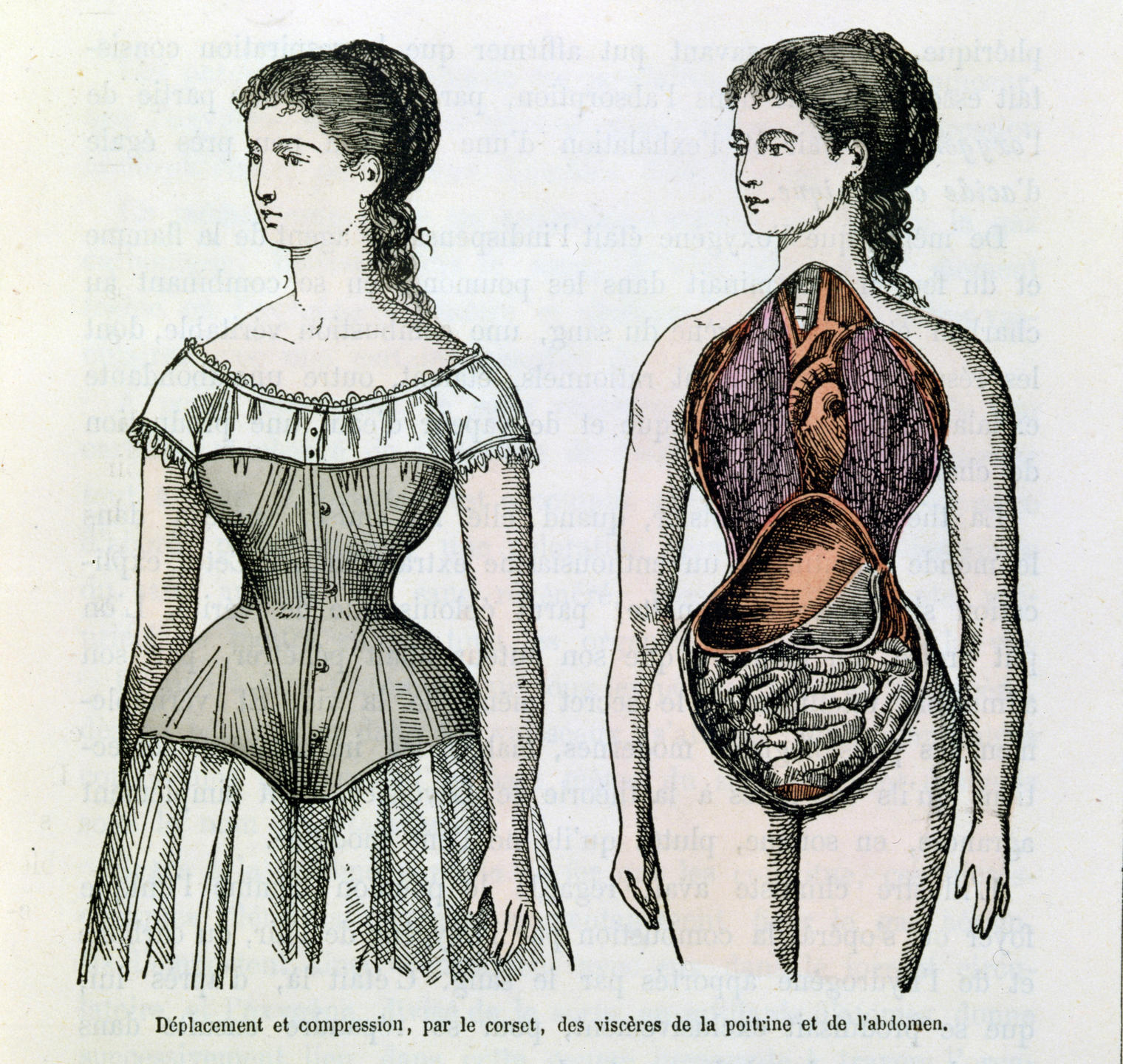

The Renaissance, a period of rapid population growth, brought about a change in the perception of people’s surroundings and bodies, with a blossoming of new artistic representations. “The Renaissance marks a rediscovery of the body,” notes Georges Vigarello of the Centre Edgar Morin.3 “Ronsard, for example, spoke of the ‘divine corpulence’ and ‘fragrant breath’ of women.” In the 17th century, Fénelon condemned vanity in his Treatise on the Education of Daughters, while Molière’s character Philaminte in The Learned Ladies exclaims: “the body, that trifle, is it of any consequence / Of a value that is even worth thinking about?” Nonetheless, Vigarello adds, “Madame de Sevigné was constantly reminding her daughter of the necessary precautions to remain healthy, keep a rosy complexion, present a pleasant appearance, etc. Later, the ideology of the Enlightenment enhanced sensitivity (and even sentimentality), grace and movement.” Rousseau called for an end to the practice of swaddling infants, some doctors began recommending walking and fresh air for women. In the pathologically prudish 19th century (women were cloaked from head to toe under corsets, petticoats and long skirts, masturbation was accused of all evils…), the number of public bathtubs in Paris nonetheless increased from 500 to 5,000 between 1800 and 1850, even though bathing was considered immoral. In short, the concept of personal care predates the second half of the 20th century or the sexual revolution of the 1960s. According to Vigarello, “Western history is punctuated by successive discoveries of the body, its sensations and appearance.”

Yet how could the body—endured, repressed and dreaded by puritanism not so long ago—undergo such a radical change of status in only a few decades, to the point of becoming an object of worship, an asset to be preserved at all costs, an essential element of personal identity? No such (r)evolution takes place overnight. First of all, technical and medical progress since the mid-19th century has revealed more and more of the body’s secrets. “It is always better understood, maintained, treated, restored and equipped,” comments Isabelle Queval of the Centre Edgar Morin. “With the decline of disease and steady rise of life expectancy in affluent countries, people have a better relationship with their bodies. ‘Accepting your body’ becomes ‘being your body.’ In other words, you can take action on it, control it, plan its future, improve it, and renew it.”

If the body has become such a focal point in Western culture, it is also because democracy, in pervading our societies, “has generalized the principle of individual decision,” Vigarello says. “As they gain autonomy, people can reflect on who they are and what they want to do. Generally, the more a society moves toward individual fulfillment, the more precedence it gives to pleasure, desire, and all things physical.” Whether it be the disappearance of the corset or the development of fitness centers and plastic surgery, the discovery of sunbathing in the 1920s or the “lab-grown” body through in-vitro fertilization, the widespread adoption of contraception (severing the old link between femininity and maternity), the success of cosmetic products for both sexes—not to mention new hedonistic rituals like massages, spas and thalassotherapy, the expansion of organic food and the promise of eternal youth offered by DHEA… For more than a century, everything has contributed to making physical appearance what Queval calls “the cornerstone of identity.”

The cult if thinness

The pervasiveness of thinness in fashion, video clips, films, and women’s magazines is further proof of this overemphasis on the body, which must be young, healthy, firm, tanned, well-balanced and functional, with no dependencies, no impairment and no visible signs of ageing to meet Western esthetic standards (which, according to Boëtsch, “tend to become global”). In our current principles and attitudes towards the body, “being obese means being fat, big and heavy. From a social point of view, it conjures up the idea of sluggishness, carelessness, and lack of self-control. It is a marginal phenomenon, not only from a medical perspective due to its associated pathologies, but also because it represents a deviation from the norm in a society based on appearance and performance. In Africa, on the contrary, an ample female body is synonymous with ‘natural beauty’," Boëtsch says.” In our society, notwithstanding the high percentage of people considered overweight (estimated in France at 67% of men and 50% of women aged between 35 and 744) or obese (20% for the same age group), the days are long gone when “being fat was a sign of opulence and affluence,” says Estelle Masson of the Centre Edgar Morin. In the early 21st century, overweight individuals “are suspected of eating more than their share, of lacking discipline and willpower. Women in particular seem to have internalized these prejudices that denigrate excess weight and value thinness.” Again, figures speak for themselves: 55% of Frenchwomen have been on a diet at least once, and 70% believe that maintaining a slim waistline is simply a matter of willpower, despite “nutritionists warning against the dangers of repeated dieting and psychologists ringing the alarm bell about the ravages of the ‘thinness imperative’ on the self-image and self-esteem of women who fail to lose weight—or of those who succeed only too well (anorexia),” Masson points out.

While male-female equality is now taken for granted, at least in theory, “women’s magazines, which keep emphasizing the importance of ‘being oneself, radiant, and fulfilled,’ nonetheless continue to impose an image of the female body that caters primarily to the male fantasy,” adds Véronique Nahoum-Grappe of the Centre Edgar Morin. “For a girl in our society, being unsightly is a serious breach of social identity rules. On the beach, topless sunbathing is not condemned on moral grounds, but rather according to the principle that ‘a woman can't strip off if she's not attractive.’ Even at the highest levels of government, beauty has a way of finding itself in the circles of power…”

The social value of thinness and beauty, and more generally the obsessive quest to improve one’s image, also has its roots in the collapse of the main religious and political systems that once offered “the possibility of programming one’s existence through a ‘Great Beyond’ (God, the Revolution…) by denying one’s individuality,” Andrieu notes. The crisis affecting traditional ideologies, the family, the social fabric, and the economy, combined with the democratization of education, encourage today's individuals to “endow the body with all imaginable powers,” he says. In a society “with no transcendence, and no collective utopia,” such as ours, the body is “the last bastion of the individual, the sole ‘material’ to rely on for self-construction, self-assertion and self-fulfillment.”

Why, then, the recent surge of activities (bungee jumping, long-distance trekking, white water rafting etc.) that put at risk bodies brought to their peak ? Georges Vigarello sees no paradox in the phenomenon: extreme sports allow participants to “recapture the experience of transcendence within their own body, and confine it to their personal space. Confronting the unknown ‘from within themselves,’ they make the body an arena for experimenting with ‘another reality’.”

Science to make dreams come true

Caught up in a “general trend for somatization,” everyone wants to “create ‘a body of their own’ one that will draw attention, using all technical and scientific means available, including nutraceuticals, hair dyes, skin creams, UV tanning lamps, grafts, implants, tattoos, piercing, etc.," Andrieu points out. "As a result, we are witnessing the ‘infinite individualization’ of the body, and the emergence of what I call a ‘hybrid identity,’ as opposed to the natural identity we inherit from our parents.” In France alone, between 150,000 and 200,000 people undergo cosmetic surgery every year.

Beyond improving people’s appearance though, surgery is increasingly able to restore damaged or ageing bodies: in France, 700,000 hip and 40,000 knee replacements are performed each year, as well as 450,000 eye implants—not to mention kidney, liver, and heart transplants. “We all hope that regenerative medicine will renew our health indefinitely,” the scientist adds. “And it is possible to imagine that the widespread use of biomechanical and electronic implants, along with that of nanotechnology, will gradually turn us into Homo orthopedicus, with artificial hearts, reconstructed faces, bionic arms, cochlear implants to improve our hearing, and miniature video cameras to replace our eyes.”

Does this body, “enhanced” and “artificialized” for the sake of performance, represent progress for humankind? Beyond the ethical issues raised by this type of technical self-transformation (how will cyborgs retain control over the devices equipping their bodies? How early in life will these alterations occur?), “the integration of hybrid beings in society challenges the biological body’s capacity to adapt to the technological invasion (what are the limits of the body’s ‘plasticity’?)," Andrieu stresses. "At the same time, it poses the problem of the social acceptability of hybrids and the radical change in current standards defining a natural body—today's normality will become tomorrow's handicap.” The prospect of wrinkle-free hybrids is proof that humans have never had so much power over their bodies. The question is whether “we are not in fact sanctifying the body for want of sanctifying the soul,” concludes Gilles Boëtsch. Mirror, mirror on the wall…

- 1. Environnement, Santé, Sociétés (CNRS / Université Gaston Berger (Senegal) / Université Cheikh Anta Diop (Senegal) / Université des Sciences, des Techniques et des Technologies de Bamako (Mali) / Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique et Technologique (Burkina Faso)).

- 2. Anthropologie bio-culturelle, Droit, Ethique et Santé (CNRS / Aix-Marseille Université / Etablissement Français du Sang).

- 3. CNRS / EHESS.

- 4. According to the results of the “Mona Lisa” survey (Institut Pasteur de Lille, Université Louis Pasteur in Strasbourg, INSERM in Toulouse, with the backing of Pfizer Laboratories) released in June 2008.

Explore more

Author

Philippe Testard-Vaillant is a journalist. He lives and works in south-eastern France. He has also authored and co-authored several books, including Le Guide du Paris savant (Paris: Belin) and Mon corps, la première merveille du monde (Paris: JC Lattès).