You are here

Lifting the Veil on Dreams

You have been studying sleep for a quarter of a century, and more specifically dreams in recent years. Has this work enabled you to define a 'normal' dream and identify aspects of dreams that are common to everyone?

Isabelle Arnulf:1 Yes, spending so many years studying patients' dreams has enabled us to determine a typical content. Our dreams are made up of 90% commonplace, ordinary things, such as talking and interacting with people we know—family, friends and colleagues. And yet the dreams that we find the most striking consist mostly of strange or disturbing events. We remember them better, because their strangeness startles us long after waking. These are what Freud called 'typical dreams,' such as losing your teeth, being naked in public, or flying through the air. Even though the latter three only account for 1% of all our dreams, 77% of us remember them. They form a sort of common dream heritage, with sometimes far-fetched interpretations. It is often said that dreaming of losing your teeth portends the death of someone close to you, or that dreaming of flying is a sign of sexual impotence.

Do we relive the previous day when we dream?

I. A.: Yes, to a very large extent, albeit in bits. Dreams don't reproduce life, but rather reconstruct it differently. They are not just a reflection of waking life, as emphasized by the British psychologist Liam Hudson. Instead, the brain's plasticity mixes our experiences and weaves them together in another way. This gives rise to a completely new story, based on events that took place during the day, combined with older memories. Indeed, although 65% of the facts present in our dreams are related to the previous day, only in 2% of cases are they an exact replay of it.

How do scientists access patients' dreams?

I. A.: Many research teams across the world are looking into the issue, using a variety of approaches. One of the pathways to dreams, used in cognitive psychology, is to collect reports on waking. When you dream, the events you experience seem completely real. When you wake up, you remember fragments of them, and then reformulate your dream—which is when we collect the report. Using a smartphone, the patient immediately dictates their dream. People are more likely to remember their dreams when awoken suddenly, while reports are longer in the morning. On average, sleepers report two dreams per week, although some prolific dreamers can recall ten dreams a night!

Dreams are by definition subjective, since they originate from personal experience and appear to be fleeting. So how can they be studied and analyzed scientifically?

I. A.: A precise list of protocols must be followed to analyze dreams. We study their presence, absence and frequency. We also define their intensity, by counting the number of words included in the sleeper's report, for example. Using this approach, researchers have established that a report containing more than 40 words necessarily corresponds to a dream during REM sleep. In addition, scales that measure the degree of strangeness or threat make it possible to divide the report into components and classify dreams. For these studies to be valid, a large number of dreams must be collected and analyzed by independent individuals. This method works very well. The data are stored in dream banks, like the one at the University of California Santa Cruz (US), which contains no fewer than 22,000 dreams.

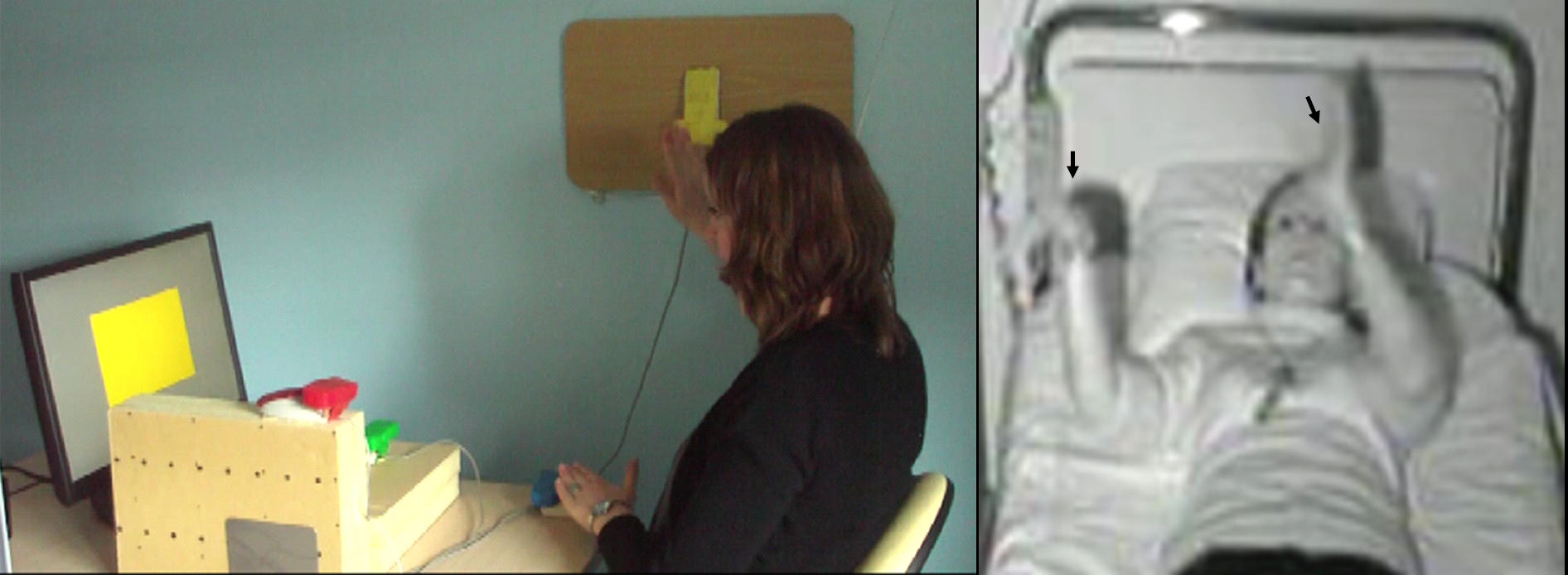

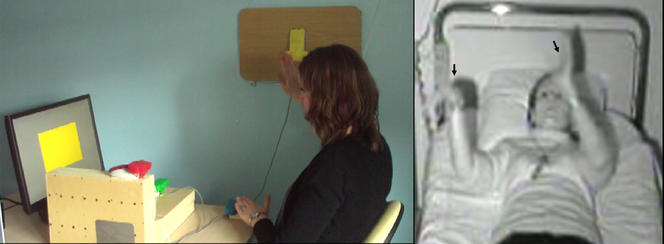

Apart from reports collected on waking, in what other ways can you access dreams?

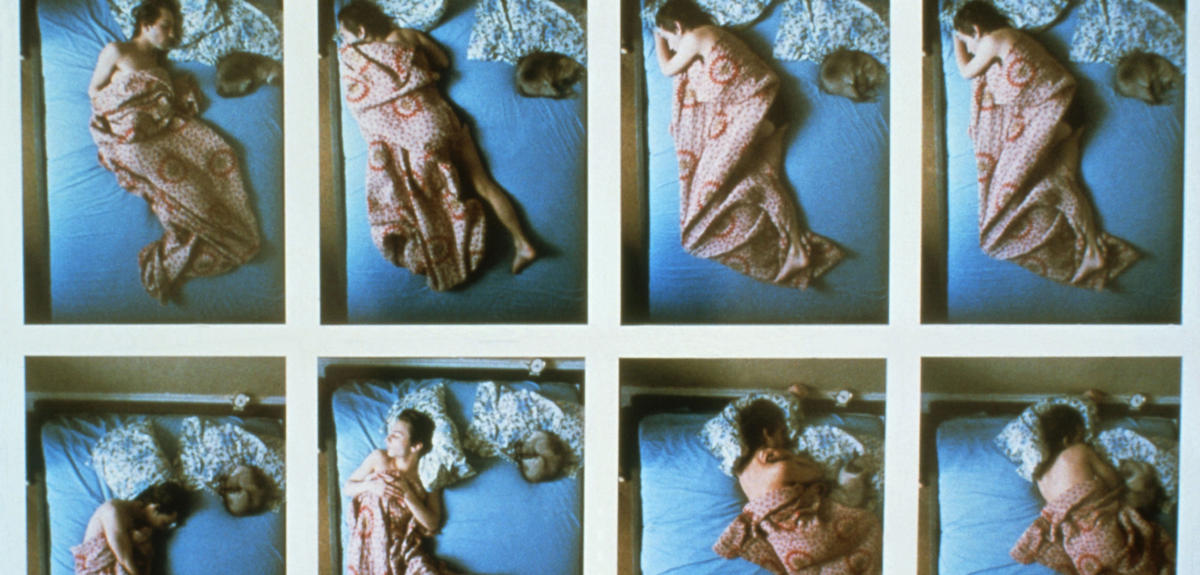

I. A.: We also study behavior during sleep: what people say while they are asleep, what they do, their facial expressions and eye movements. While the body is normally paralyzed during REM sleep, it is important to bear in mind that facial expressions are conserved. Moreover, in some sleep disorders like sleepwalking, the body is mobile and sleepers even mimic their dream in bed, which provides us with information about mental content. It is a bit like observing a dream from the inside!

Another insight into dreams is through brain imaging and electroencephalograms, often used to observe regional brain activation during sleep. In fact, this is one of the methods that enabled us to show that dreams are experienced live during sleep, which some scientists doubted until recently. We also investigate the visual and auditory hallucinations that take place in disorders such as narcolepsy. These are fragments of dreams that suddenly occur while people are fully awake. Lastly, studying lucid dreams is also a good way of directly accessing dreams. Lucid dreamers are aware that they are dreaming and can control the scenario of their dream in their sleep.

When dreaming, blind people can see and the deaf can hear! Doesn't this show that dreams are not solely based on our real lives?

I. A.: The source of our dreams is complex. Dreams can allude not only to our day and to our feelings, but also to our perception of the world and to that reflected back to us by those around us. The question is: do our dreams have an innate or acquired origin? To find the answer, research is increasingly shifting towards the study of patients deprived of a sense (sight, hearing or speech) or motor skill (paraplegics and amputees, whom we have studied) from birth. The results are striking. When they dream, the dumb can speak, the blind can see, paraplegics can walk, and 50% of deaf people can hear. So how can someone who has never heard a sound in their life manage, in their dreams, to hear their neighbor talking on the phone? Dreams might even have the ability to awaken senses that we don't know about. One theory is that there may be a genetic program in our brains that prepares us to walk, see, hear or smile before we are born. This program is thought to be activated when we dream. In the womb for example, infants smile in their sleep, as do newborns before they can even do so when awake! Concerning the blind, another hypothesis is that they transform the image of the world they have made for themselves , through their fingers for instance, into a mental representation that they reactivate when dreaming. During sleep, paraplegics from birth, on the other hand, may well put themselves in the shoes of the walkers they see every day, which reflects our ability to empathize.

According to dream banks, 82% of dreams are of a violent or negative nature. This is contrary to popular belief that they are an escape to a better world. How can this discrepancy be explained?

I. A.: The threatening and violent nature of dreams could actually be beneficial! Dreams prepare us for danger, in the safe haven of sleep, to help us deal with it better in real life—in the same way as a chess player anticipates his opponent's moves to win the game. Indeed, threatening situations in dreams often take the form of conflicts, among colleagues or in the family. We studied medical students' dreams the day before their exams. Most of them foresaw disastrous situations: the students missed their train, couldn't understand the questions, or were forced to write on bread! Lots of negative experiences, which eventually proved helpful: the more the students had dreamed about the exam, the better they did. The reason could be simple: dreaming about the exam reduced their anxiety. Some people take a Darwinian view of this phenomenon. In their opinion, simulated threats while dreaming have helped human beings survive and reproduce. This theory makes perfect sense when studying the dreams of young mothers—their baby is in danger, suffocating or has fallen out of bed—which probably make them better prepared to protect their baby.

So sleeping on a problem does help solve it?

I. A.: Yes. It improves our reasoning. Some illustrious scientists and inventors have found the solution to their problem in their sleep, including Singer, the inventor of the sewing machine, and Mendeleev, the chemist who developed the periodic table of the elements. Moreover, it is well known that sleep and dreams facilitate learning. Students who dream about their lectures remember them better.

Yet dreaming has other purposes. It is also very effective at breaking down the day's emotions, which the brain screens during the night in order to better eliminate negative feelings. Studying the dreams of recently divorced individuals has confirmed this theory. And the results are unambiguous: those who cope best with the situation are also those who dream the most about their former spouse! Dreaming eases their sadness, helping them pull through in the long term. In the end, dreaming is thought to cheer us up.

Could the power of dreams and sleep be used to treat certain diseases?

I. A.: There are avenues of research concerning Parkinson's disease. Firstly, sufferers gesticulate and cry out while dreaming, sometimes years before they develop the condition. Identifying these troubled nightmares would make it possible to anticipate and monitor the disease, sometimes up to ten years in advance! Secondly, we have observed an incredible phenomenon in patients with Parkinson's: their movements while asleep are normal, rapid and jerky, rather than slow and trembling. Besides, their voice is more intelligible and their face more expressive. But as soon as they are woken up, their body stiffens again. In the middle of the night, the wife of a sufferer found her husband having a nightmare, crouching on the bed and waving an imaginary sword. His gestures and words were clear and lively. Yet when she woke him, he could no longer move or get back into bed. When awake, sufferers' movements are slowed by a negative effect from the basal ganglia. This disorder appears to be suppressed by sleep, disinhibiting the premotor areas, i.e. the regions of the brain that are activated before we make the slightest movement. This mechanism is being studied in the hope that we may eventually be able to alleviate the symptoms of this extremely incapacitating disease.

In your book, Une fenêtre sur les rêves (A Window into Dreams), you define dreams as 'one of the brain's most interesting cognitive activities.' Why does the 'science of dreams' appeal so much?

I. A.: I find it important to emphasize that dreaming is a cognitive activity, because this is actually novel. Until now, research rather sought to draw a symbolic or psychoanalytic meaning from dreams. We weren't used to considering them as a form of mental activity pertaining to consciousness, in the same way as memory and learning. This is no doubt because dreams seem intangible and specific to each individual. Yet the same goes for other fields that have nonetheless been the subject of scientific studies, such as pain or empathy. So it seems logical to analyze the characteristics of dreams in the laboratory. Dreaming is an extremely interesting cognitive activity since, as we have seen, it enables us to think, learn, and cope with our emotions better. Dreams also fascinate me because they shed light on the purpose of sleep. Studying them is definitely worth it!

- 1. Professor Isabelle Arnulf is a Doctor of Medicine and of Neurosciences, head of the Sleep Disorders Unit at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris (France), and a researcher at the ICM Brain and Spine Institute (CNRS / UPMC / Inserm). She is the author of Une fenêtre sur les rêves ("A Window into Dreams"), published by Odile Jacob.

Explore more

Author

Léa Galanopoulo has a biology degree and is currently studying scientific journalism at Paris-Diderot university.