You are here

Versailles, from one Century to the Next

A treasure trove has been hidden away in the drawers of France’s National Archives and National Library (BnF). But not for much longer! Some 7,500 plans of the Palace and Estate of Versailles dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries will soon be fully digitized.1 From mid-December, these plans will be available online on the Palace of Versailles Research Centre (CRCV) website, and on the National Archives website in two years’ time. This will be of great interest not only to the general public, but also and above all to historians.

“From the hunting lodge built by Louis XIII in 1623 right up until 1837 when Louis-Philippe turned the Palace into a museum space (and in doing so removed nearly all of the toilets, which gave rise to the enduring clichés about the filthiness of the court), Versailles has been continuously converted to meet the needs of successive sovereigns and to provide accommodation for, among others, their families, courtiers and ministers,” explains Mathieu da Vinha, scientific director of the Palace of Versailles Research Centre (CRCV). Some rooms mentioned in the historic documents no longer exist in the Palace that we know today. And some passages no longer make sense, to the point that when reading period documents, historians sometimes wonder how people actually got around the buildings! Hence the idea, in addition to the huge digitization task launched in 2013 as part of the Verspera project,2 to use these thousands of plans to create a 3D model of the Palace and reveal its secrets at all stages of its history.

Mignard’s Gallery under Louis XIV (3D reconstruction by the Verspera project)

Originally a hunting lodge built by Louis XIII—who had fallen in love with the Estate during his time spent hunting there as a child—it was under Louis XIV that the Palace took on the external appearance that we know today. The king had seen in this a potential for expansion that was not offered by the Louvre, and started the works in 1661 after the death of Mazarin and upon taking power. Louis XIII’s building is surrounded by what is now known as “Le Vau’s Envelope,” a stone façade by the architect Le Vau who also built the new wings for the outbuildings, stables and State Apartments. His successor, Hardouin-Mansart, closed off the Palace’s Italian terrace which became the Hall of Mirrors, and started erecting the majestic North and South Wings on each side of the central building. More than fifty years of construction work followed, during which time the king, his family and the entire court lived among the noise, smells and dust!

As Louis XIV was passionate about architecture, he wanted to closely monitor the progress of the works, showing little concern for the discomfort it would cause his entourage. “In 1682, the pregnant Dauphine moved into the Palace, but could not put up with the smell and went to live a little further away, with Madame Colbert,” says da Vinha. Louis XV did not extend the Palace any further, preferring renovations, particularly in the private apartments. The birth of intimacy in European societies also gave the sovereign the right to completely secluded spaces. As a result, he built cabinets that opened onto the courtyard and in which he could hide from the gaze of the court. He also set up apartments for his daughters—who were eight in total, the oldest being the only one to marry. Rooms were reconverted, decors moved, and mezzanines created—to such an extent that although the Palace’s central building originally had only three levels, it ended up with seven!

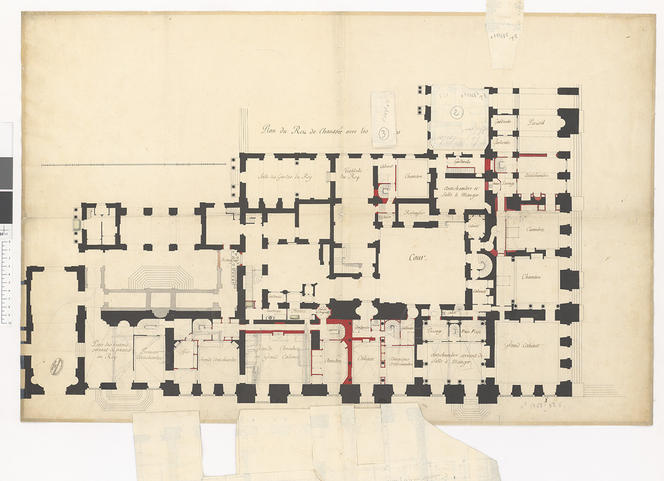

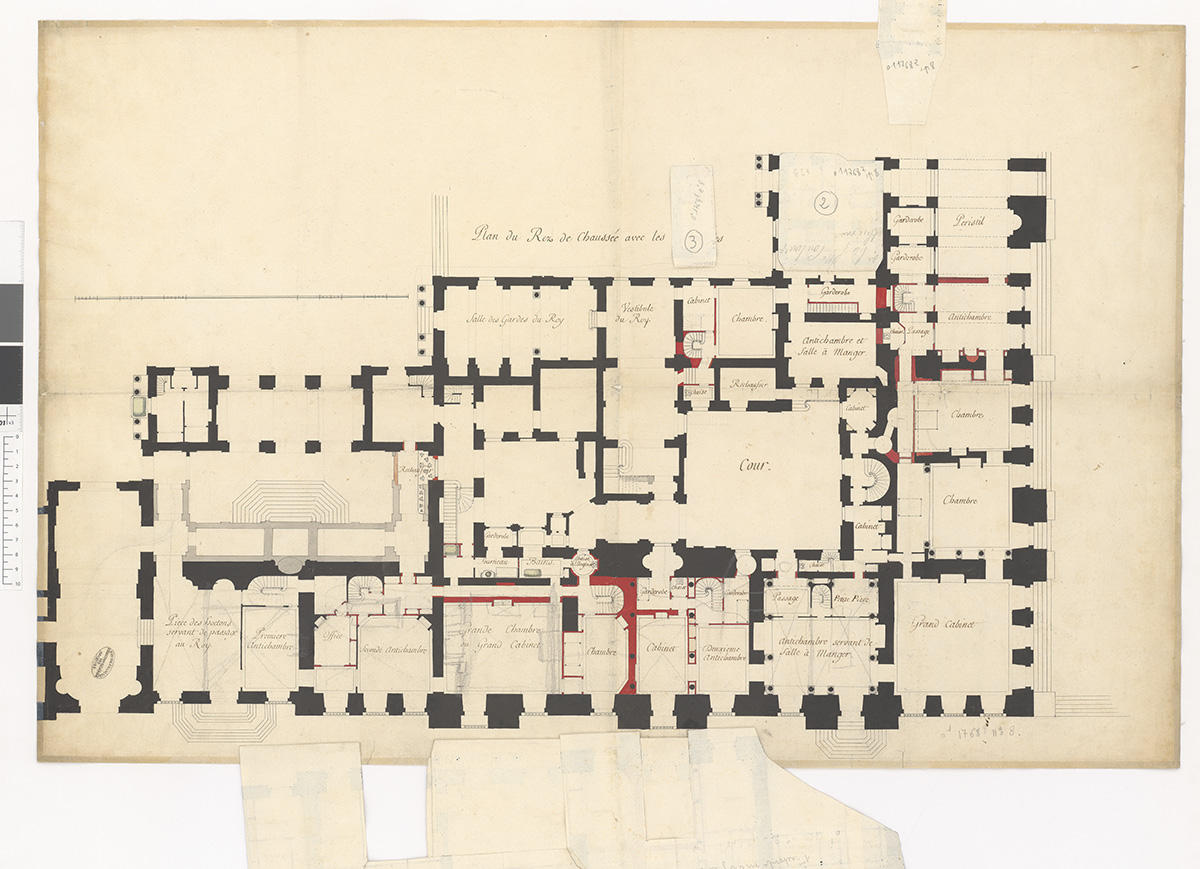

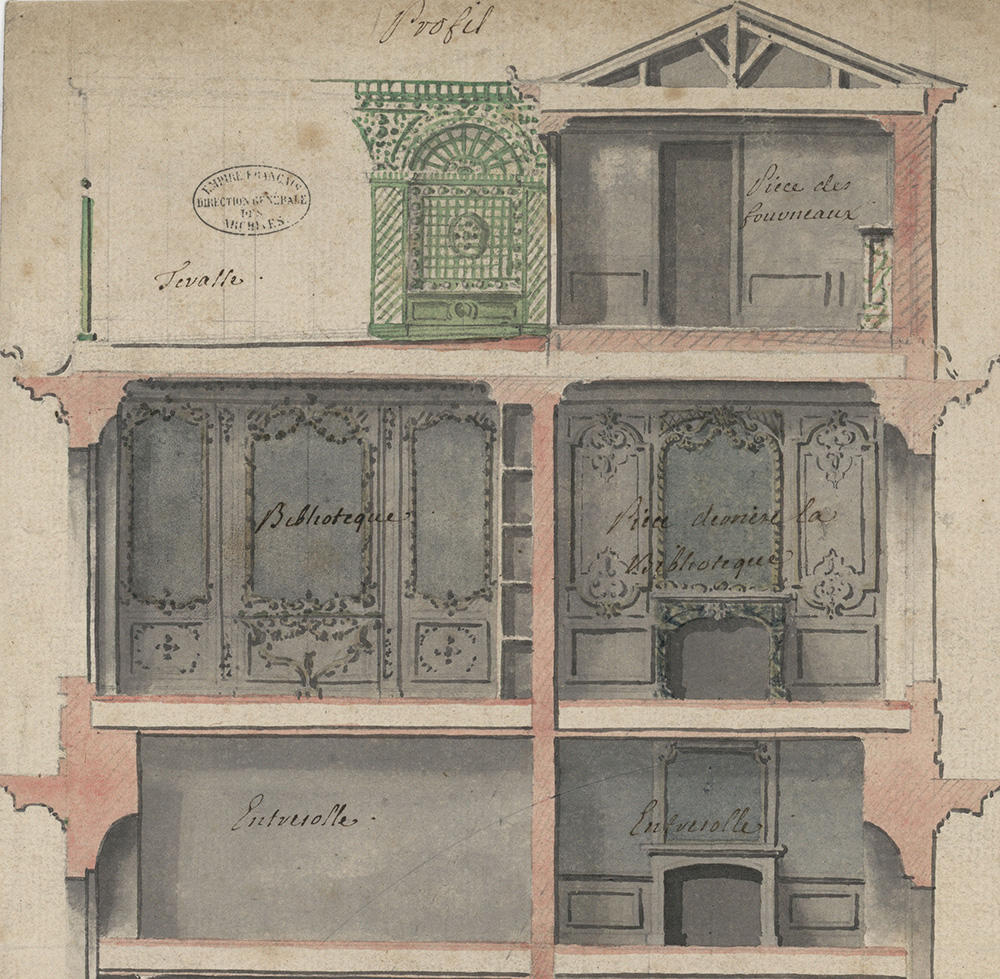

While the advantage of 3D modeling to retrace changes in the Palace is obvious, this is not an easy process. “The plans from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are not codified like the ones we use today,” says Michel Jordan, research engineer at the ETIS3 laboratory, specialized in digital image processing. “They are a sort of hybrid between artists’ drawings, which can be nicely watercolored, and architects’ plans”. The formats are by no means standard either. “Some plans are 3cm x 4cm, but the largest ones can reach 3m by 4m,” says Pierre Jugie, curator of the National Archives, who oversaw the digitization of these documents and the restoration that was sometimes necessary (10% of all plans had to be restored). “There were fold creases on some of the plans that hadn’t been unfolded for centuries. And once they had been digitized, these creases could be mistaken for walls or partitions."

The modeling software had to learn to circumvent these pitfalls in order to extract the relevant information from the patchwork of digitized documents: in addition to “classic” floor plans, there are also cutting patterns revealing floors, mezzanines and elevations. Invaluable for the reconstruction, these documents show walls and facades and often include decorative elements such as stuccoes, chimneys and woodwork. Another distinguishing feature of these period plans that certainly complicated the digitization process, is that some of them have up to twenty overlays (flaps stuck onto the main plan, as tracing paper had not yet been developed) that enabled the architects of the time to offer variants, mention a detail or show another level.

Mignard’s Gallery shown in the featured video is the very first space to be recreated in 3D with the Verspera software. Originally one of Louis XIV’s apartments, this area (in the right wing of the central building, on the first floor, around the marble courtyard) then became home to his mistress Madame de Montespan. From 1685, the king used it to exhibit his works of art, including his collection of Italian paintings, one of which was the famous Mona Lisa. The 15-m long gallery, whose ceiling was painted by Mignard, is lined with paneling and flanked by a salon at each end. It is preceded by several rooms, such as the Seashell Room. “Other areas will follow,” says da Vinha. “The main long-term goal is to trace the developments of the king’s private apartments over three centuries, but also to show some of the projects that never came to fruition”.

The only limitation is that Verspera will only go as far as the archives will reveal. The rule is to stick to the information provided in the documents, even if it means leaving large areas blank or producing a few quirks. The Bull’s Eye Antechamber that was created in the king’s private apartment in 1701 by joining two rooms together, appears to be perfectly rectangular on the Hardouin-Mansart plans, but in reality it has a trapezium shape. “On the ground, the architect had to adapt to the exact configuration of the surrounding rooms,” says Jordan. Versailles is more fascinating than ever!

- 1. Digitization was made possible by FSP (Foundation for Cultural Heritage Sciences) funding.

- 2. Verspera is a project led by the FSP (Foundation for Cultural Heritage), CRCV (Palace of Versailles Research Centre), National Archives, BnF (National Library of France), ETIS, and the joint research unit ENSEA Cergy.

- 3. Equipes traitement de l'information et systèmes (CNRS /ENSEA /Université Cergy-Pontoise).