You are here

The Vel d’Hiv Roundup: Shedding new light on a French crime

How would you explain the Vel d’Hiv Roundup to someone who has never heard of it?

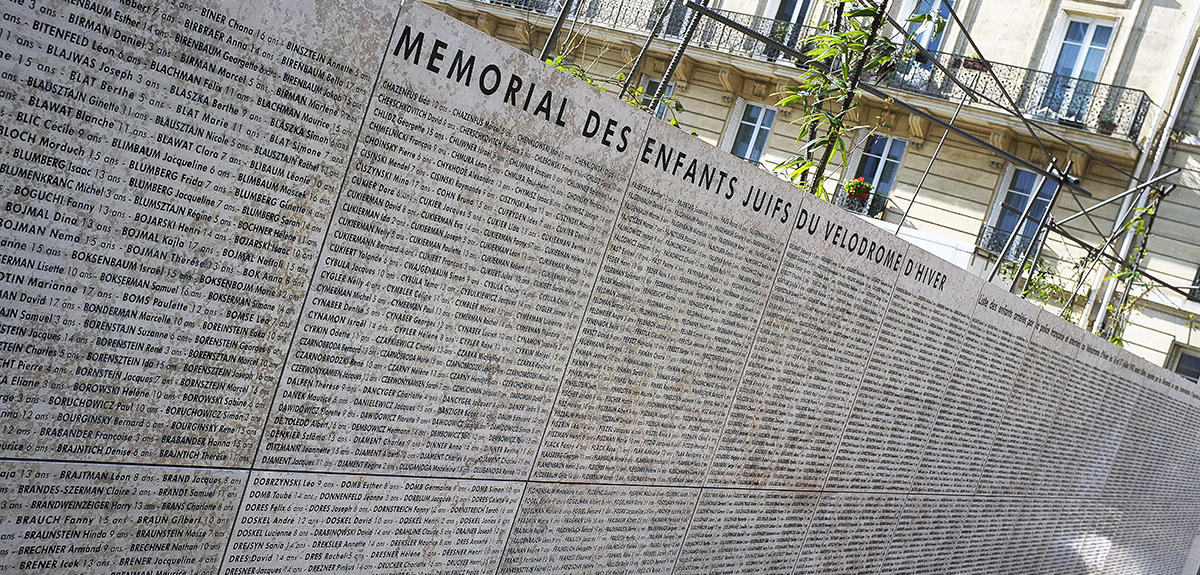

Laurent Joly:1 I would start with the name. A ‘roundup’ means that people were rounded up in mass arrests. These were not individual, isolated police actions. It was a vast operation by the Paris police force targeting 35,000 foreign Jews and their children (most of whom were French, having been born in France) in Paris on 16 and 17 July, 1942. In less than two days, a total of 12,884 people were arrested.

Then there is the ‘Vel d’Hiv’, or Vélodrome d’Hiver (“winter velodrome”), a sports arena in southwestern Paris. The arrested families were detained there, not knowing what would happen to them. The Germans did not clearly state what was to be done with the prisoners. At Auschwitz (Poland), the gas chambers were ready but the crematoria were still being built. The Nazis needed a bit more time before deporting the children, who were all headed to the gas chambers, unlike the adults, some of whom would be held in the camp to die from forced labour. In the end, nearly everyone arrested was deported within two months. Only about 100 of these victims would survive.

It was the largest roundup in Western Europe during the Second World War. (Other such large-scale operations, in unoccupied France, in Berlin (Germany) and in Amsterdam (The Netherlands), later claimed about 5,000 to 6,000 victims.) To carry it out, the Nazis needed the collaboration of the Vichy regime and the French police. It was the concrete implementation of the Nazi genocide policy in France. At the same time, there is something horrifyingly prosaic in the way the event unfolded. Only ordinary public servants were involved – police officers, bus drivers, etc. The fact that children were arrested and isolated from their families shocked part of the public, who could not understand what was behind the announced separations and deportations in different convoys.

What historical research had previously been done? And how is your investigative book different?

L. J.: The mechanisms of the collaboration were already well known, especially through studies by historians like Michaël Marrus, Robert Paxton and mostly Serge Klarsfeld. We knew in broad terms what France’s government, politicians and administrative services did to turn over thousands of Jews to the occupying forces. On the other hand, little work had been done on gathering and analysing testimonies, especially concerning the role of the police in the roundup. In the past 30 years or so, the sources have been at once abundant, extraordinarily widely disseminated, and sometimes buried among thousands of archive documents. The only research book available, published in 1967, was La Grande Rafle du Vel d’Hiv by Claude Lévy and Paul Tillard, two former members of the Resistance. This important report, based mostly on moving testimonies, made a strong impression when it was released. But it’s also an ‘activists’’ account, by definition incomplete. In the 1960s the government archives were still sealed – they weren’t opened until the 1980s, and unrestricted access has only been available for 20 years.

I had to start the investigation over from scratch, based on what I could find out today, in order to write a book for the general public retracing this tragedy in all its dimensions while correcting the misconceptions that have been circulating for more than 50 years. These include the myth of the code name ‘Opération Vent Printanier’ , the involvement of militant collaborationists in the arrests, the rumour of hundreds of suicides, etc. All while fine-tuning the figures and integrating new elements, such as the roundup after the roundup, a low-key operation that continued through the end of August 1942 and resulted in the arrest of an additional 1,200 victims.

How did you proceed in analysing these new sources?

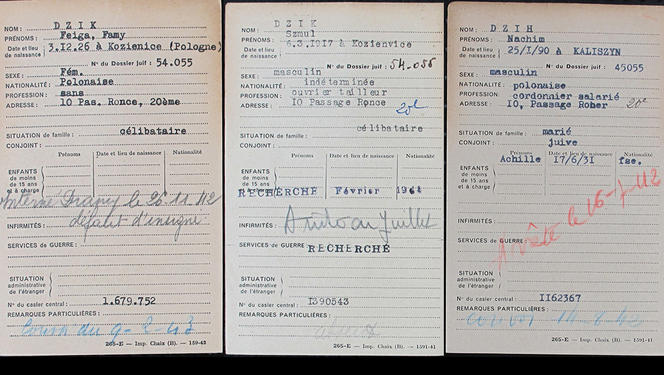

L. J.: One of the main problems arose from the fact that many archives were destroyed after the war. Most of the documents dealing with the administrative, logistical and police preparation have been lost. On the other hand, in the past 20 years we have had access to what are called the ‘Jewish files’, compiled by police headquarters to keep track of the Jewish population in Paris and the suburbs. Cross-referencing these documents with a database set up by Serge Klarsfeld from detailed lists of the convoys of all the Jewish deportees from France, I was able to identify 90% of the people who were arrested on 16 and 17 July, 1942. Another important source was the so-called ‘administrative purge files’ – documents from after the Liberation incriminating police officials accused of ‘collaboration’. There are about 4,000 such files, which have been available to researchers for the past 20 years. The only possible approach was simply to read them one by one.

In the end I was able to identify 150 that were directly connected to the roundup and its aftermath. These files are a rich source of information. They contain statements made by policemen (to justify their actions), accounts by victims and by concierges (often damning), and copies of arrest reports – all totally new material. In particular, they give an indication of the police officers’ mindset and their margin of manoeuvre, whether they had the capacity to save some of the Jews or whether, on the contrary, some showed excessive zeal… Different situations emerge, which partially explains the sharp variations from one part of Paris to another. In the centre of town, for example, only 27% of the foreign Jews on the lists were arrested, compared with 36% in the outlying districts and 42% in the suburbs.

More generally, what did you glean from these previously unexamined documents and accounts?

L. J.: They make it possible to reconstruct what happened in extraordinary detail, for example concerning the role of neighbours and concierges. At the time, the names of a building’s tenants were not visible anywhere, as they are today on mailboxes and interphones. Everything depended on the concierges, who distributed the mail and collected the rent. The police had to ask them to identify the families in order to make the arrests. As it turned out, the concierges’ attitudes differed greatly from one building to another. Some would claim that the people on the list were absent, even knowing that this was not true. Others, on the contrary, urged officers to search more thoroughly if they thought someone was still hiding in the building.

Back then, rent was collected every three months, on the 15th, and the day before the roundup, which began on 16th July, was a collection day. The concierges knew exactly who was present and under what names. By comparing the documents that I found with other sources, like the handful of arrest reports in our possession, I was able to piece together the entire history of a neighbourhood or a building during the roundup.

Why weren’t these documents studied earlier?

L. J.: Finding and cross-referencing them was a difficult, time-consuming and often fruitless task. You could spend weeks sifting through hundreds of purge files without finding any mention at all of the Vel d’Hiv Roundup. Then other times you might be luckier and discover a wealth of information in the very first file you put your hands on. In addition to this painstaking work, you have to know where to look for pertinent sources and how to identify them. It was easier for me because I’ve been working on these issues for more than 25 years. My doctoral thesis was about the files compiled by the agents of the CGQJ, the Commissariat-General for Jewish Affairs, which was in fact a government ministry for anti-Semitism during the Occupation. I have also done research on the archives of the Vichy special services and the denunciation of Jews during the Occupation.

I’m used to examining these types of documents and linking them to a context or to otherwise-known events. In any case, all of this data, as well as the archival collection work that I’ve done, are now available for any historian who wants to investigate further.

Were any accounts especially striking, interesting or moving?

L. J.: Yes, of course. Especially since I wrote my book while contributing to a documentary film in French that gives voice to witnesses and survivors of the event. Naturally, I was very moved when the testimonies of people who had lived through the roundup resonated with the archives that I had been studying. All of a sudden, history takes on a depth and substance that no paper document can convey. There is something ineluctably compelling about hearing the accounts of people who have lived through the events that you’re describing when they were barely 8, 15 or 17 years old. Today, 80 years after this tragedy, it’s important to understand that we are no doubt seeing the last major commemorations in the presence of these witnesses and survivors. We must encourage these narratives and give them the attention they deserve before it’s too late. For us historians, it makes us feel humbler about the potential impact of our research, while showing that our work is all the more necessary as a means of preserving and transmitting the record of these accounts.

Could you mention any examples?

L. J.: The Dziks are an emblematic case. At the time they were a poor family, with a disabled mother and a chronically ill father. One of their sons was arrested and then released from the Drancy transit camp, near Paris, for medical reasons: he suffered from severe psychological problems and had an ulcer. Two of their daughters, Esther and Fanny, escaped the big roundup but were left to their own devices. Fanny was arrested in November 1942, at age 16, and Esther was taken into custody at a Métro exit checkpoint in August 1943. By coincidence, both sisters ended up in Auschwitz. When Fanny was losing the last of her strength, she begged Esther to survive: ‘Promise me now – you still have a chance. The war will be over soon. If you make it, do everything you can to go back and tell what happened.’ Fanny died that same night, but Esther did survive. Today she is 94 years old, and continues tirelessly to tell her story. She was one of the people I met, and her account is a common thread in both my book and the documentary.

I also think of people like Jenny Plocki, who was 17 at the time. With her younger brother, she managed to get away from a holding centre in Vincennes (Paris), but then had no money to pay rent. She found a way to get some kind of benefits, sought help from various sources and somehow was never arrested. Testimonies like hers describe what survival conditions were like in Paris for those who avoided arrest. Not everyone had the means to leave for unoccupied France, and some couldn’t even live decently. But Jenny Plocki survived and is still testifying today, at age 96.

What do you think about the evolution of the public debate and points of view on the Vel d’Hiv Roundup in recent years?

L. J.: The historical facts are increasingly well known, and there is no longer any real debate in the research world on the French government’s responsibility for the Jewish deportation policy. There is still room for discussion on some specific points, for example the reasons for periodic declines in the number of deportations, or how Jewish people’s status evolved during the Occupation. But there is no controversy concerning the overall dynamic. For the general public, Jacques Chirac’s speech in 1995 also expressed this consensus in well-chosen, courageous terms.2

Unfortunately, it is also clear that, in parallel, certain forms of historical falsification are gaining ground. For example, I take part in training sessions for schoolteachers, and in the past ten years they have regularly encountered students who – repeating what they hear at home – claim that the Vichy regime did everything it could to save the French Jews. It’s difficult not to see a link with the rising prominence of the falsehoods put forth by Éric Zemmour, an extreme right polemicist who ran for president in the last election. I recently published a book that deconstructs his misleading rhetoric in French. Twenty years ago I never would have imagined that I’d ever have to do such a thing. But that’s also the historian’s role: to put the facts right and remind everyone what the events in question really meant for the people who lived through them.

For further reading:

La Rafle du Vél d’Hiv in French, Laurent Joly, 25 May, 2022, Grasset, 400 p., €24.

La Falsification de l’Histoire. Éric Zemmour, l’Extrême-Droite, Vichy et les Juifs in French, Laurent Joly, 5 January, 2022, Grasset, 140 p., €12.

Film:

La Rafle du Vel d’Hiv, la Honte et les Larmes (“The Vel d’Hiv Roundup, Shame and Tears”), documentary in French, 102 minutes, Roche Productions, France Télévisions, 2022, directed by David Korn-Brzoza, written by Laurent Joly and David Korn-Brzoza, broadcast on 11 July on France 3 and 17 July, 2022 on France 5 television channels.

Explore more

Author

Fabien Trécourt graduated from the Lille School of Journalism. He currently works in France for both specialized and mainstream media, including Sciences humaines, Le Monde des religions, Ça m’intéresse, Histoire or Management.