You are here

The Natchez and the French, from alliance to tragedy

In the past few decades, France has entered a process of coming to terms with its colonial history. How does the North American chapter of this history differ from the rest, and do you think that it should be better known to the general public?

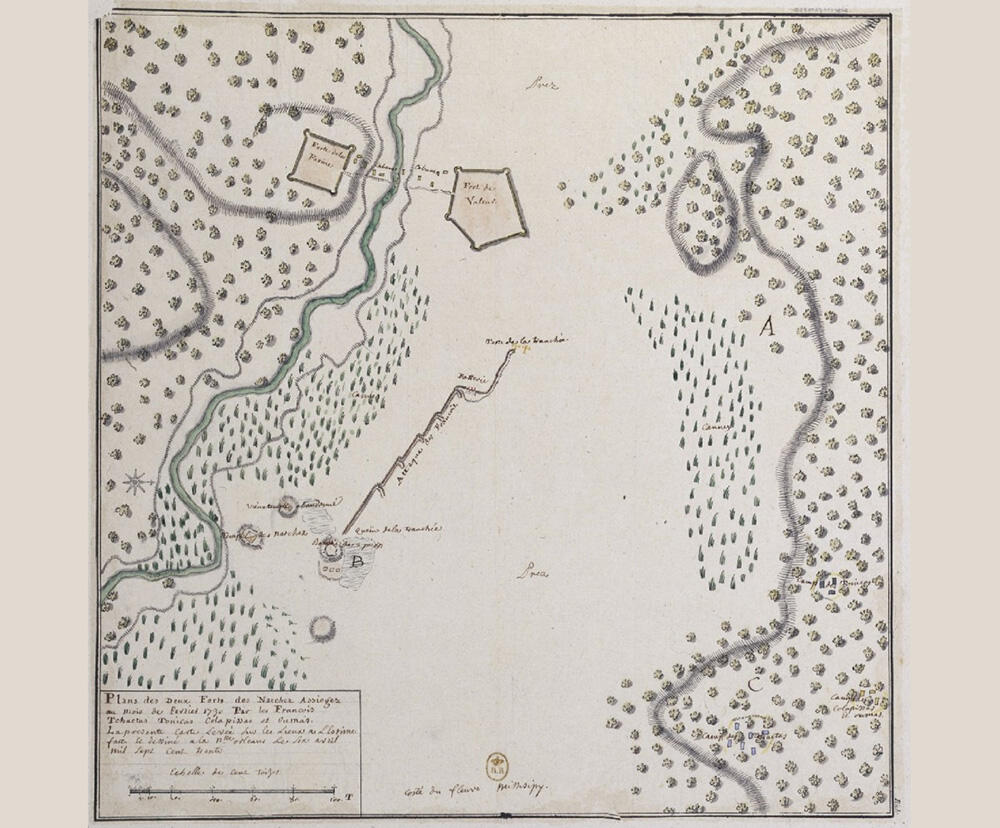

Gilles Havard1: First of all, it’s a forgotten part of history, largely because the North American portion of the French colonial empire had essentially disappeared before the Revolution of 1789, a watershed for France’s national identity. Secondly, the history of the settlers in North America is indissociable from Native American history. Due to their small numbers, the French had to form alliances with the natives, whether in Canada, Acadia or the Mississippi Valley. For example, the ‘Natchez Outpost’ was founded in about 1720, 300 kilometres north of New Orleans, with the approval of the local tribes. The Natchez, who numbered about 4,000 in the early 18th century, were in no way subjugated by the French.

In the 1720s, some 400 French settlers arrived in Natchez territory to grow tobacco, bringing around 250 black slaves. Originally their presence was based on friendly relations and sharing of know-how.

Every summer the settlers participated in the great Natchez green corn ceremony. They also benefited from the yields of the natives’ hunting and called upon native healers. For their part, the Natchez were eager to acquire rifles, cooking pots and woollen fabrics like those of their French neighbours. This intercultural confluence broadens our perception of the colonial phenomenon in all of its variety and complexity. Even though they sought to establish sovereignty, the French forged diplomatic relations with native North Americans similar to those that existed between European nations at the time. The French were also often dependent on the natives economically and militarily.

In addition, many settlers set out to adapt to local customs, rather than imposing their own. This was especially true for the so-called coureurs de bois (“forest runners”, Ed’s note) – fur traders who lived among the natives. In fact, this undermined the colonial enterprise, because the ‘Indianisation’ of these men, who often took indigenous wives, hindered the intended converse effect: the ‘Frenchification’ of the natives.

And yet, despite these harmonious relations, a revolt broke out in Louisiana in 1729, which is the starting point of your book. Why this sudden surge of violence?

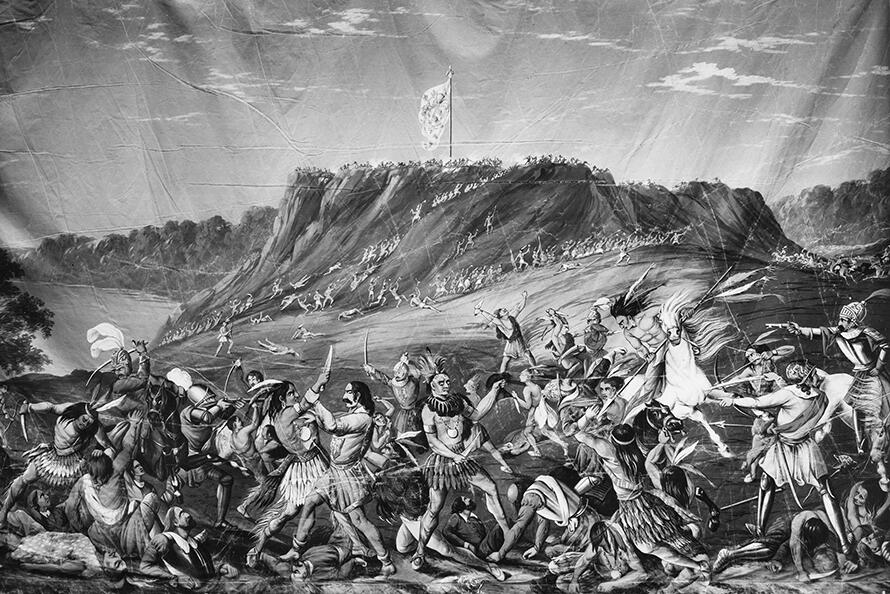

G. H.: In fact, my intention was to examine this event to determine whether it was a genuine anti-colonial uprising. It needs to be reconsidered from an anthropological point of view, taking into account the Natchez people’s attitudes toward death and violence. In my book, I explore the ritual dimension of violence in an attempt to highlight two phenomena overlooked by historiography. Firstly, the ethnic aggregations in that part of the world always had a potential for brutality. One example is the massacre of 200 Mougoulachas by the Bayagoulas in 1700, even though the two groups had coexisted for several years.

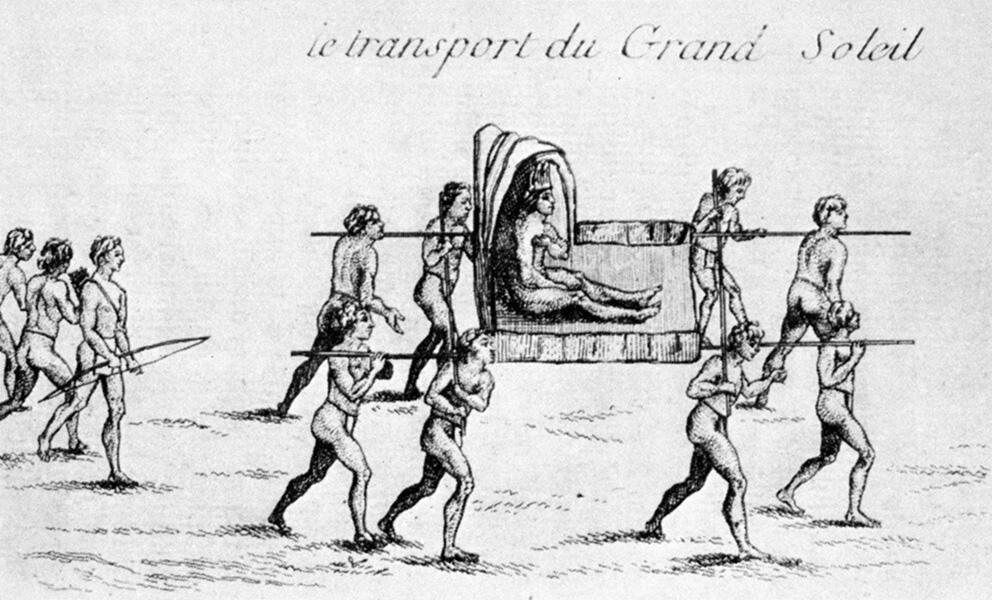

Secondly, I wonder if the French were not themselves victims of a ritual that could be called the ‘funeral sacrifice’. The Natchez saw the settlers as potential kinsmen and therefore subject to the community’s rules, including this practice. In fact, upon the death of a Sun (the name given to the local aristocracy), the deceased’s servants and relatives – sometimes totalling dozens of individuals – were strangled in order to accompany them to the land of the dead. Death was contagious. I believe that the Natchez attack was both an act of war (taking scalps, abducting women and children) and a domestic sacrifice.

What makes the Natchez so unique, in relation to other Native American peoples? Why did you choose to study them?

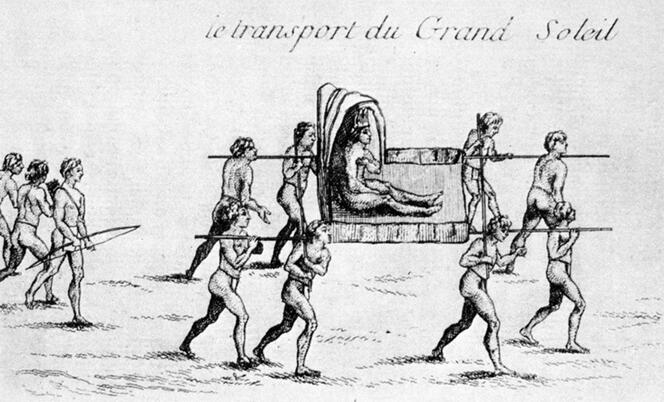

G. H.: The Natchez case poses a threefold enigma. Anthropological to start with: for the French, this society stood out for its strict hierarchy and its organisation based on complex, spectacular rituals. At the top was a supreme leader called the ‘Great Sun’ (who was not at all a despot, contrary to what Montesquieu claimed in his writings), followed by four social classes: ‘Suns’, ‘Nobles’, ‘Honoured’ people and, at the bottom of the ladder, the ‘Stinkards’. But this division was not permanently fixed: a Stinkard who brought back a scalp could join the Honoured. And the rules of marriage were such that, for example, the child of a Stinkard father and a Sun mother became a Sun.

In addition, Natchez society had a long history as part of the ‘Plaquemine’ culture, an offshoot of the so-called ‘Mississippi’ civilisation (11th-16th century AD). The latter was characterised by monumental architecture, building platforms and mounds topped with dwellings or religious structures. The most spectacular example is Cahokia Mounds, near the present-day city of Saint Louis. As mentioned above, there is also the historical enigma: why did the Natchez suddenly kill nearly 250 French settlers in 1729, after 30 years of coexistence mostly characterised by a relation of alliance?

Lastly, the Natchez offer a fascinating example of resilience. They still exist today despite the two great upheavals that have marked their history: the French military onslaught in the 1730s that led to their dispersal and partial extermination, with some being deported as slaves to Santo Domingo. Then, a century later, the forced relocation by the Americans of the surviving Natchez to present-day Oklahoma, after they had taken refuge with the Creeks (in Alabama) and the Cherokees (North Carolina). There were still a few Natchez speakers in the early 20th century, and in fact the language had changed very little from the time of the first French settlers.

Europeans heard of this tribe for the first time in 1826, with the publication of the book Les Natchez by Châteaubriand. How do you, as a historian, view this literary heritage? What do you think we owe to its author?

G. H.: It began with the success of Chateaubriand’s novels Atala and René (1801 and 1802), inspired by his journey to North America in 1791. He rekindled popular interest in New France and, for the entire first half of the 19th century, even shaped the French public’s knowledge of America with its majestic forests, mighty rivers, and wise or barbaric ‘Indians’. Chateaubriand sketched the outlines of a fictitious Indianness in the Western imagination, even though he based his descriptions on authentic ethnographic elements: porcelain necklaces (wampum), the peace pipe, manitous, the day of the dead, torture stake, the tree of peace, etc.

In that vein, what method do you use to extract facts from more or less fictionalised accounts in a context like this?

G. H.: Although we have almost no information on many tribes of the lower Mississippi Valley, the colonial chronicles from the early 18th century often mention the Natchez. It’s something of a documentary ‘miracle’, but of course we have to take a critical view of these sources. In their reconstructions of the Natchez attack of 1729, the chroniclers were influenced by various models from books – tragedies, conspiracy stories, fables, picaresque accounts – that blur the boundaries between history and literature.

In addition, we have to remain open to comparisons with other Native American populations, especially in consideration of the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss. In analysing the ritual violence, or the power of the chief, correlations can be established with the Aztecs, for example. Lastly, in terms of methodology, one must call upon the work of the American anthropologists who met the last Natchez speakers in the early 20th century. The field notebooks from the 1930s of the linguist Mary Haas offer precious data on the Natchez oral tradition.

Nearly 300 years after the conflict, you have proposed a totally unprecedented initiative: a ‘treaty of reconciliation’ between the French and the Natchez. What more can you tell us about it?

G. H.: In 2022, I was able to meet Hutke Fields, the current chief of the Natchez, in Notchietown in eastern Oklahoma, and travel with him to Natchez, Mississippi, where a powwow is held every year with Natchez participants. He was the one who suggested the idea, and I contacted the French embassy in the United States. It would be a reconciliation ceremony with no actual legal value. The plan is to hold it in Natchez in March 2024.

What community is served by this treaty, and how would you define their claimed identity, given that the Natchez language is no longer in use, along with most of the tribe’s customs and practices?

G. H.: Since 1996, Hutke Fields has held the title of ‘Great Sun’, which had not been borne since the 18th century. He leads a Natchez government consisting of another chief and four ‘Clan Mothers’. He is also trying to reconstruct the language (he can speak of bit of it himself) and is seeking recognition for the Natchez Nation from the American federal authorities. This would give the Natchez access to health and social programmes as well as funding that could support, among other things, the revival of a dormant language. It’s a genuine process of reinventing a culture and reviving traditions (marked in Oklahoma by the existence of ceremonial grounds where native dances are performed). But the situation is quite complex, because the Natchez are legally considered to be Cherokees or Creeks, tribes already recognised by the federal government. And the Cherokee and Creek governments are not eager to see the Natchez acknowledged as a political entity in their own right.

Is this newfound Natchez identity the ‘sacred fire’ mentioned by the tribe’s ancestors?

G. H.: The sacred fire of the Natchez – which symbolised the Sun and therefore life – was meant never to be extinguished: transported to Chickasaw territory, where the Natchez first took refuge in the 1730s, it was then brought to the Creeks and Cherokees before being moved to Oklahoma in the 1830s. Today, the current Great Sun says that the ashes from the fire are at his home, in his yard. The Natchez hope one day to rekindle the ‘fire’ of a ceremonial dance ground (Medicine Spring), which has been ‘resting’ for several decades. ♦

References

Les Natchez. Une histoire coloniale de la violence, Gilles Havard, Tallandier, “Histoire” collection, January 2024, 608 p., €26.90 (in French).

- 1. Gilles Havard is a CNRS research professor at the Mondes Américains laboratory (American Worlds laboratory – CNRS / EHESS / Université Paris Nanterre) and a specialist in the history of Native American-European relations in North America (16th-19th centuries). He is the recipient of the 2020 CNRS Silver Medal.

Explore more

Author

Kyrill Nikitine is a freelance writer and journalist. He writes for Télérama, Science & Vie, La Revue des Deux Mondes, We Demain, and Le Débat Gallimard.

He is the author of the story Le Chant du derviche tourneur (2012).