You are here

"Sociology needs to reconnect with science"

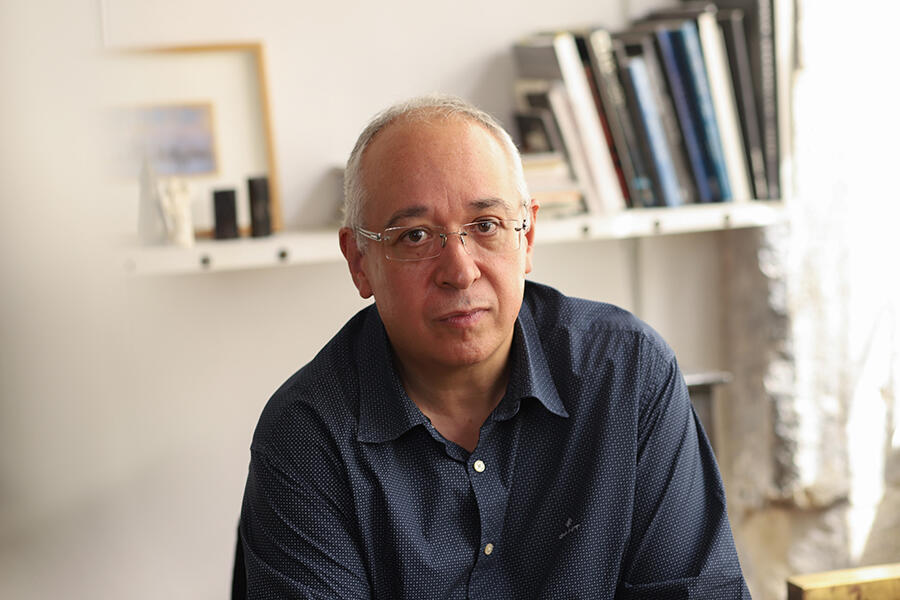

Bernard Lahire has dropped a bombshell with the publication of Structures Fondamentales des Sociétés Humaines (“Fundamental Structures of Human Societies”, La Découverte, 2023). In nearly 1,000 pages, the CNRS research professor at the Centre Max-Weber in Lyon (southeastern France)1 re-examines some 150 years of sociological practice that in his view has strayed too far into hyperspecialisation and become isolated from the life sciences. In the past 30 years, his own research has focused on a variety of topics ranging from school dropout rates to political action, illiteracy and artistic creation. But he has long felt the temptation, dating back to his doctoral dissertation, to expand his field of investigation to other disciplines like history, psychology and linguistics, along with a need to reconsider the status of the social sciences, a subject broached in his most recent work2. His current proposals to revolutionise sociology are the fruit of these years of reflection.

You want sociology to break out beyond its borders, but how did it become, much to your regret, so hyperspecialised?

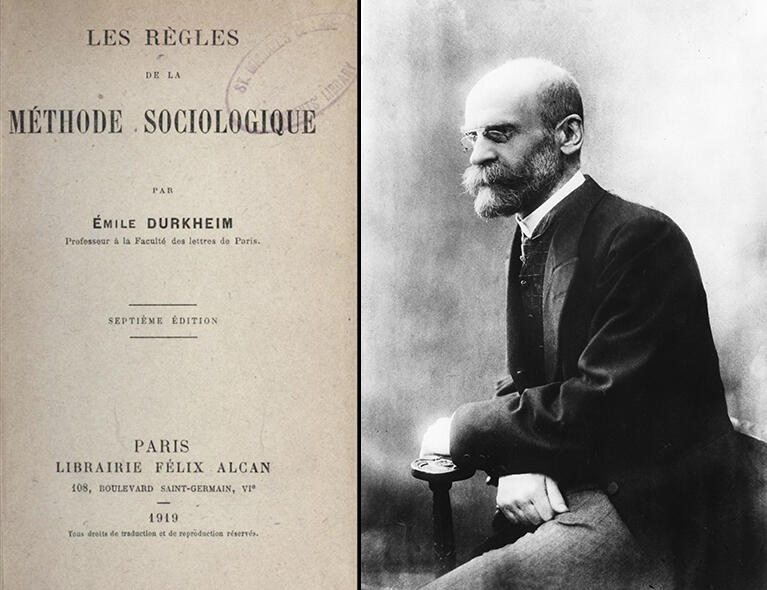

Bernard Lahire: The earliest sociologists understood that they needed to find a specificity in their discipline in order to give it academic legitimacy. Émile Durkheim, who nonetheless explored questions at the interface of psychology and sociology, for example, furthered the effort to isolate sociology unto itself. He tried to define its territory so as not to encroach on the psychologists, telling them, in essence, ‘Your focus is the individual, ours is the collective’. This was a primal error, and one for which I have often criticised him, because I believe that the individual is fundamentally social, which means that the social cannot be reduced to the collective.

Durkheim also held strongly entrenched positions in relation to biology. He believed that animals depend on instinct and their actions are pre-programmed, whereas humans rely on learning. However, long before the advent of ethology, in 1877 the sociologist Alfred Espinas published a thesis on animal societies upholding the idea that social interactions are not specific to humans. But he was ahead of his time. For sociologists, the most important thing was to establish an academic discipline, which therefore had to be based on human life within society.

You lament in particular that, unlike other scientific disciplines, the social sciences have shied away from formulating universal principles, like the law of gravity in physics or evolution in biology…

B. L.: I was increasingly troubled by the idea that the social sciences were ‘doomed to remain forever young’, as Max Weber put it. Many sociologists have embraced this notion like a mantra: because we work with historical material that is constantly changing, we cannot do research like the other disciplines, in particular conducting experiments. I didn’t see why we, as sociologists, historians or anthropologists, should be incapable of defining general principles or laws, or of laying the basic foundations of our disciplines after more than a century of research, instead of starting over again from scratch every time. Just as the law of gravity means that we don’t have to verify each morning whether some objects remain suspended in the air while apples fall to the ground.

Certain disciplines, like cosmology and evolutionary biology, are by nature non-experimental sciences. They are observational, like the social sciences, but still they are able to establish broad general principles. As the anthropologist Alain Testart said, no two planets are exactly the same, but that hasn’t prevented astronomers from formulating laws. Also, the Universe is constantly changing, as galaxies die and others are born. Nothing is more changeable than the transformation of species, and yet Darwin defined laws that govern their evolution.

All of which has led you to say that the scientific spirit must regain control over the social sciences. How can this be accomplished?

B. L.: By the comparative method, which in fact was central to Testart’s work. He said that it was impossible to understand capitalism without correlating it with wealthless hunter-gatherer communities, to feudal and lineage-based societies, etc. A systematic comparison of very different social systems is the best way to identify the invariants and characteristics specific to each type of civilisation. The next – and most radical – step is to compare human and non-human societies.

As outside observers, we are easily able to identify the basic structures of certain animal populations, for example the exogamous practices of chimpanzees, where females join another group in order to reproduce. But we are rarely capable of identifying the basic structures of our own human societies, because we are so engrossed in their variations. So we need to find a way to observe them from the outside, comparing them with other non-human animal communities.

When I undertook this project, and in the course of reading the ethologists, I discovered that many mammalian societies avoid incest, whereas Freud and Lévi-Strauss maintained that the incest taboo was a distinguishing trait of humanity. Through this type of comparison, we see that certain laws prevail among multiple species and are not exclusive to our own. In short, I started out with an epistemological objective, namely that the social sciences must become like the other scientific disciplines, capable of formulating laws, of defining their established principles and identifying our societies’ fundamental structures, in order to use them to move forward. And to that end, I have undertaken comparisons between human societies as well as between them and non-human societies.

You use the example of learning to show how cultural life is not the exclusive prerogative of the human species…

B. L.: There are in fact elementary forms of learning, for example what we call habituation, among all living things. But we also find social learning throughout the animal kingdom. In mammals and birds, the young watch and imitate the behaviour of the experienced adults. We have also observed actual forms of teaching, which presupposes the parents’ ability to conceive a progression that enables their offspring to figure things out little by little. This can be seen in meerkats, which feed on scorpions in the desert. At first, the adults hunt a scorpion and pluck off its stinger, making it harmless without killing it, which allows the young meerkats to learn how to handle their prey. In the next step, the adults hunt the arachnid and merely stun it, leaving the stinger. Under their supervision, the young learn how to manipulate a more dangerous specimen. In the third and final step, still under their control, the adults give their offspring a scorpion that hasn’t been stunned.

Learning is not limited to animal societies…

B. L.: The learning process has even been found in single-celled organisms like the slime mould called ‘the blob’, which is neither animal nor fungus nor plant… Even though it doesn’t have a nervous system or brain, the blob experiences habituation – in other words, it is able to recognise salt or caffeine, realise that they pose no danger and, after a while, move across a surface drenched with such a substance. If a blob is subjected to stress at regular intervals, such as being exposed to extreme cold or heat at specific times of day, it will anticipate those moments and go dormant, as though it were no longer alive. This means that there is a mechanism, as yet unknown, that allows it to internalise regularity and anticipate future events. This type of behaviour shows that life is directly linked to the capacity to learn. In fact, isn’t one of the basic criteria for the very definition of life the ability to extract information from one’s environment and draw the consequences in order to adapt?

But how does one proceed from these observations of life forms to sociological laws?

B. L.: By showing that certain biological properties that we have inherited from evolution have fundamental social consequences. The fact of having offspring that develop extremely slowly, requiring long-term nurturing from adults, results in a species that is attentive to others, accustomed to providing care and mutual assistance. When the offspring are especially demanding, the phenomenon of monogamy sets in, in particular among birds, because the mother cannot do everything alone, leaving the young ones unattended. A division of labour is established between father and mother, with a little more collaboration than in other species.

In humans we also have to consider what is called secondary altriciality, which means the very long, very strong, energy-consuming period of children’s dependency in relation to their parents. This can even lead to a reliance on ‘parents’ from outside the couple. Moreover, because childbirth is so difficult and risky, it must be a socialised or collective event. Consequently there are a great many factors pressuring humans to band together and help one another. But the long, strong dependency of human children also gives rise to a parent-child relationship of domination, which is one of the key mechanisms that have structured human societies. What was originally a matter of biology ultimately became a social fact: there is domination in all societies, in the relations between the sexes, in the economic, political and magico-religious spheres, etc. This holds true even though its forms are constantly varying and transforming.

In your book you formulate 16 universal laws and 10 lines of force defined as human traits. Can you give us some examples?

B. L.: First of all, I want to specify that this list is by no means exhaustive and needs to be expanded. For example, it has been noted that all human societies have an economic facet and modes of production, as Karl Marx pointed out. Although their form can vary widely, these modes of production constitute a social dimension that has been present since the beginning of humanity, along with domination, the sacred realm, symbolic expression… For another example, I also formulate the ‘Westermarck effect’, named after a Finnish anthropologist, on the avoidance of incest. This law is found in all societies, albeit with social consequences that differ depending on the type of society, and even the type of group within a given society. We have seen in the history of human civilisations what has been observed in physics, where the law of gravity works in the same way everywhere, but doesn’t always produce the same effects: due to frictional forces, a heavy airplane won’t fall in the same way as a feather.

Doesn’t sociology have a lot to lose by establishing general laws at the expense of the statistics and high-precision measurements it has long held dear?

B. L.: Obviously that’s not the idea! Striking just the right position is certainly not easy: if we’re overly general we end up saying nothing, and if we’re too specific it has no scientific utility. Of course the social sciences will continue to produce highly detailed monographs on a given situation, in a given place, within a given type of society. But, as in physics or biology, the objective is to identify the established knowledge upon which we can build in order to investigate specific realities that have never been studied before.

Statistics allow us to single out certain regularities, but ‘regularity’ does not necessarily mean ‘law’. In the case of school dropouts, for example, figures clearly show that children inherit their parents’ social properties. But these are mere observations, statistical regularities. Formulating a law of conservation-reproduction-extension, on the other hand, means compiling the findings of many projects that recognise this type of regularity, incorporating cultural, economic and other factors across very different communities. This makes it possible to conclude that it’s a mechanism that operates in all societies.

Consequently, general laws are by no means a hindrance to the discovery of specific phenomena. On the contrary, they turn out to be an asset, by structuring the study of historical reality. Even though an event always has a random component, it is still a precipitate of a number of factors structured by laws. Until our disciplines bring such laws to light, they can have no genuine claim to the status of science. ♦

For further reading

Les Structures Fondamentales des Sociétés Humaines (in French), Bernard Lahire, La Découverte, August 2023, 972 p.