You are here

Edgar Morin turns 100, and continues his journey

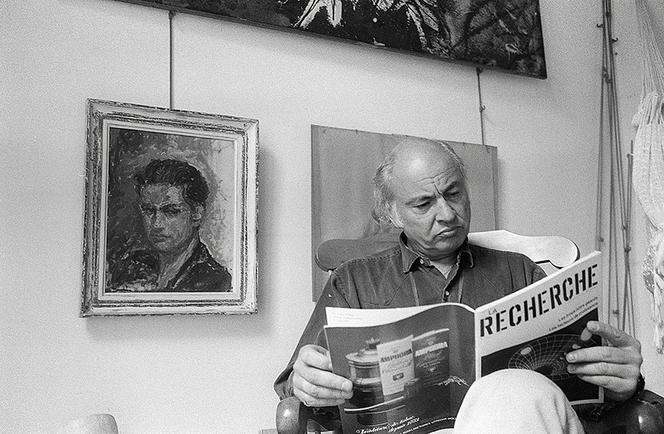

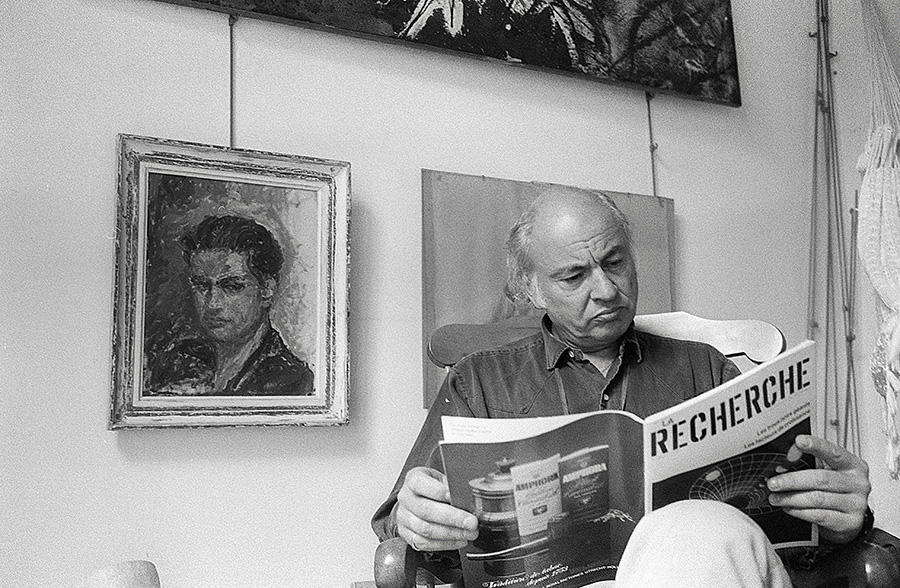

“My life is an intellectual journey in the course of which my thinking is constantly being shaped. But this journey was never mapped out and my line of thought has never reached an end. It is still evolving to this day.” The spark in his eyes speaks for him: even as he celebrates his centenary, Edgar Morin remains more eager than ever to find out about the next significant event. On 2 July, to mark the beginning of a busy week of tributes and ceremonies, the CNRS senior researcher emeritus gave a masterly demonstration of his far-ranging intellectual travels at UNESCO, intertwining Kant and Stalin, football and ecology, biology and miscellaneous news items.

Genesis of a “humanologist”

The Morin method began to take form, he recounts, in his teenage years, when he still went by the name of Nahoum. Between the crises afflicting democracy and capitalism, Hitler’s rise to power and the Moscow trials, “All of the alternatives seemed horrendous. Adopting Kant’s formula, I wondered: ‘what can I know, what can I believe, what can I hope?’” Seeking answers to these questions, the young secondary school graduate, already involved in politics through his support for the Spanish Republicans, entered university in 1939, where he studied philosophy, psychology and sociology, as well as political science history. He was already transdisciplinary, with the ambition of becoming what he calls a “humanologist”, in other words a thinker capable of understanding the nature of humanity by uniting all these forms of knowledge.

Also influenced by Marx and his desire to understand societies, along with their history, economic development and future, Nahoum the student became Morin the resistance fighter before conducting his first field research in occupied Germany. As explained in his recent memoirs, Leçons d’un Siècle de Vie (“Lessons from a Century of Life”), the motivation for the project was his curiosity at a complex phenomenon: how could the most cultivated nation of Europe become the most inhuman of all? The investigation grew into a book – the first of a long series, numbering as many as his years on earth. In L’An Zéro de l’Allemagne (“Germany Year Zero” – Éditions de la Cité Universelle, 1946), the budding sociologist strove to understand what was going on in the heads of the people who believed in Hitler and then ceased to believe in anything.

Yet this did not exactly launch his career. Finding himself out of work, Morin spent two years haunting the libraries, gathering research material to write L’Homme et la Mort (“Man and Death”, Corréa, 1951), which remains his bestselling book worldwide. For the sociologist and CNRS senior researcher Claude Fischler, “That publication stood out as a model, like the prototype of Morin’s work, with his basic interdisciplinary approach, taking an interest in biology, history, mythology, etc., while at the same time examining the full complexity of attitudes towards death.”

How are we to understand, Morin asks, that death can inspire such horror, and yet we are ready to give our lives for our children, our family, our country? In his UNESCO presentation, he explains how this long endeavour led him to distance himself from Marxist thought as he discovered that “imagination, myth, beliefs and religions have as much reality as the material and economic world. In truth, dialectics is like a wheel that goes from the material and economic to the mind and the imagination or to mythology…”

While he was working on this book, in 1950 the CNRS offered him a position. “A wonderful opportunity”, he emphasised in a recent discussion, because the institution, although pigeonholing him as a sociologist, granted him total freedom. Morin immediately began navigating among several disciplines. No research topic was negligible; each investigation spawned its own method. Utterly free in his movements, he became the walker lauded by the Spanish poet Antonio Machado, for whom “paths are made by walking”.

A complex, visionary thinker

The path was not laid out, but it took shape around certain practices that would guide the development of Morin’s complex mode of thinking throughout his life. Starting with the “side step”. “The side step is a change of viewpoint on the complexity of the world, enriching your perception of things,” explains Jérémi Sauvage, senior researcher and lecturer in the language sciences at Université Paul-Valéry Montpellier (Lhumain laboratory) and a member of the “Reliance et Complexité” group. “My research focuses on how children learn a language,” he says. “It’s a complex phenomenon and I have to approach it as such, without trying to make it binary, even though that makes everything more difficult. How do I do that? By taking a step to the side, thus changing my point of view, taking into consideration the behavioural sciences, psychoanalysis… In short, by getting away from my own data.”

For Morin, this kind of confrontation of viewpoints often takes place by bringing together researchers and scientists from a range of disciplines, allowing everyone to enlighten everyone else. In his intellectual biography, he pinpoints the 1972 Royaumont (Paris region) seminar on “The Unity of Man” as a turning point. With Jacques Monod, he gathered some 30 biologists, physicians, anthropologists, historians and psychologists to reflect on “biological and universal cultural invariants”.

A few years earlier Morin had also been part of the “Groupe des Dix”, a “Group of Ten” founded on the same principle of transdisciplinary cooperation. Within this circle he learned from cyberneticists about the concept of the feedback loop, which he considered fundamental because it challenges the principle of cause and effect, which was long considered inviolable.

Royaumont also marked a time when palaeontology was drastically pushing back the origins of mankind, and when the gap between the human and animal worlds, once considered colossal, was greatly reduced: speaking at the seminar, R. Allen and Beatrice T. Gardner described how they had succeeded in teaching sign language to chimpanzees.

From the Royaumont seminar came Morin’s book Le Paradigme Perdu: la Nature Humaine (“The Lost Paradigm: Human Nature”, Seuil, 1973), in which the researcher develops his concept of the human being as a combination of three inseparable elements: the individual, the species and society. The individual exists within society, but society, with its culture and language, exists within the individual; the individual is within the species, but the species, with its DNA, is present in the individual. At the same time, Morin does not hesitate to question the Darwinian dogma of evolution by natural selection alone, dedicated as he is to understanding how other mechanisms like culture can play a role in the evolutionary process.

The biophysicist Massimo Piatelli-Palmarini, now a biolinguist and professor of cognitive science at the University of Phoenix, Arizona (US), was also present at Royaumont, where he found himself in the thick of the debates, quite heated at times, on neo-Darwinism. Today he pays tribute to Morin: “Already at that time, not only had he foreseen the direction biology would take, but he was also absolutely right to warn us against the Darwinian principle of natural selection of the fittest. He duly insisted that evolution is not related exclusively to selection, and that other mechanisms are at play.”

Temerity and “unworthy” subjects

The Italian researcher also implicitly praises his elder’s courage – by no means a universal trait – for challenging enshrined principles. Indeed, temerity is another quality that has guided Morin on his journey. “He has always had the courage to pursue his investigations and dissensions to the very end, to the point of being able to conceptualise them as a transformational experience,” enthuses Anne Lieutaud, a researcher at the Centre for Applied Research and Study in Perceptive Psychoeducation (CERAP) in Portugal. “His boldness gave me confidence and a taste for adventure when I switched from the exact sciences – the environmental and engineering sciences – to qualitative ‘inexact’ science.”

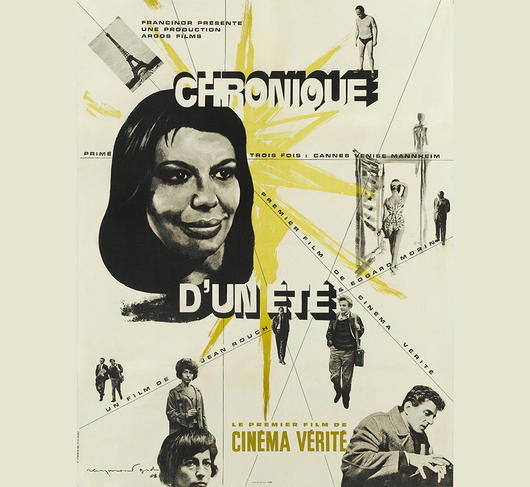

Morin was brave enough to break boundaries between compartmentalised disciplines, and to investigate all kinds of fields, such as cinema, with his book Le Cinéma ou l’Homme Imaginaire (Éditions de Minuit, 1956, published in English as The Cinema, or the Imaginary Man). The intellectuals at the time had nothing but contempt for films, and mass culture in general, which they saw as pure alienation.

Fischler recalls his participation in several projects with Morin, which left a lasting impression: “As a young student I was absolutely overjoyed and even fascinated that he could take a deep interest in football or TV game shows. When I said to him we shouldn’t tell our colleagues that we were watching the Euro Cup, he replied, ‘in order to understand mass culture, you have to experience it yourself’.”

There followed other subjects that were “unworthy” in the eyes of academic research, including the film Chronique d’un Été (Chronicle of a Summer) with Jean Rouch in 1961, and then La Métamorphose de Plozevet (The Metamorphosis of Plozevet, Fayard, 1967), a book in which the close, minute observation of a small town in Brittany (northwestern France) illustrates the far-reaching changes taking place in post-war French society. Two years later came La Rumeur d’Orléans (Rumour in Orléans, Seuil, 1969): a rumour, fanned by antisemitism, spread in the city that young girls were being kidnapped in clothes shops by an international Jewish-led prostitution ring. These atypical investigations were nonetheless conducted according to strict scientific procedures. As Fischler reports, “In Plozevet, Morin was on site for months. He personally led the interviews and was quite authoritative. In Orléans, he gave very precise instructions to the researchers working with him, just like the following year for Rumour in Amiens.”

In praise of criticism

Those instructions included the requirement that each participant keep a logbook, as per another key concept underlying Morin’s work: the necessity of accounting for subjectivity. “Keeping a journal,” Fischler says, “was based on the idea that, far from renouncing subjectivity in order to – supposedly – observe phenomena objectively, this journal should on the contrary integrate it into reality, so as to become aware, through self-examination and self-criticism, of the way that subjectivity can interfere with our perception of the real world.” This insistence on self-criticism would be a feature of Morin’s entire life and oeuvre, first in factual terms, when he published Autocritique (Self-criticism, Seuil, 1959). In that book he officially broke with communism, but, more importantly, explored the reasons why he deluded himself during his six-year membership in the Communist Party. After that point, he made self-examination a permanent aspect of his own research and urged all other scientists to follow suit.

Gil Delannoi, a political expert and senior researcher at Sciences Po Paris, is one of those who heeded his advice. “Morin redeemed the very concept of self-criticism,” he says, “in the sense that he rescued it from the ignominy attached to the term since the communist dictatorships. Self-criticism does not mean the kind of self-accusation encouraged by totalitarian regimes. In addition, and I am grateful to him for this, he understood it in a Popperian sense – Popper posited the Falsification Principle as a condition for all scientific theory – and in its two-sided relation to science, which draws its strength from its fragility.”

Delannoi further explains how this concept of self-criticism would lead Morin to distinguish doctrine, which is a kind of armour leaving no room for contradiction, from theory, which is always open to new arguments. “One can expect all intellectuals to be intelligent,” the political scientist concludes, “but they would also need to be curious, the way Morin can be for all data. He describes himself as a ‘sub-Marrano’ like Montaigne 16th century French philosopher, eager to learn, but always critical. I would say that he is also a disciple of Rabelais 16th century French humanist writer, with a desire to be soaked with knowledge.”

Morin could also be considered a follower of Rabelais for his love of life and of other people. Even though the idea is never mentioned in any epistemological or sociological treatise, his work would not have been quite the same without human interaction. To work, discuss or even argue with him is also to experience his benevolence and, often, to feel admiration for the man – or even adulation in the case of his most devoted partisans (or should we say “fans”?). This is especially true in Latin America, where the French thinker enjoys immense popularity. To the point, some say, of discouraging any critical approach to his work. In Argentina, Leonardo Rodriguez Zoya, who teaches research methodology at the University of Buenos Aires, is dismayed by this idolatry: “Of course, we must thank Edgar and celebrate life,” he says, “but we must also be able to criticise his ideas in order to keep moving them forward! And that’s not easy, because we tend to see him first as a friend rather than a thinker.”

The path of the “improved” human

And what does the thinker himself think? Even though he is appreciative of the outpouring of admiration and affection, he also expresses a degree of disillusionment about the influence of what he considers his major work, La Methode (The Method, Seuil, 1977-2004, 6 vol.). In this magnum opus of nearly 2,000 pages, the fruit of 30 years of labour, Morin formalises what he sees as the best way to acquire knowledge, investigating in a sense the state of the knowledge on knowledge, far from binary thinking, reductionism and the compartmentalisation of the sciences. In 1982 he also published Science avec Conscience (Science with a Conscience, Fayard) to highlight the works of scientific philosophers like Gaston Bachelard, Karl Popper and Michel Serres, which he thinks every researcher should read. “In vain,” he laments.

To conclude his lecture at UNESCO, he recalled that “already in the 1930s, Husserl had shown that the sciences are blind unto themselves. Unfortunately, this remains true today: the sciences do not think about themselves. They see only isolated objects”. Worse still, new myths appear. Transhumanism promises us an illusory immortality, along with the intelligence to deal with everything, thereby feeding new myths. For whose benefit? “That of an augmented human,” Morin warns, “constantly seeking more power, profit and control, to the detriment of creativity and freedom.” But another path is, of course, possible: an upheaval that would help raise awareness of a common destiny and would use the extraordinary possibilities of technology to improve our lives, human relations, education and culture, and to preserve our environment.

In other words, long live the improved human, not the augmented human. “Beware though,” Morin adds, “this doesn’t mean dreaming of a different society, but rather knowing that we are living the human adventure, and that each individual journey takes place within an immense common journey whose interactions cannot all be predicted.” Although for decades he has displayed a sharp sense of things to come, Morin refuses to prophesise, always seeing the future as an uncertain experience. Which does not preclude a few words of warning.

Bibliography

Leçons d’un Siècle de Vie, Edgar Morin, Ed. Denoël, June 2021, 160 p.

On our website

“Uncertainty is intrinsic to the human condition” (interview)

Edgar Morin: In praise of complex thought (interview)

https://news.cnrs.fr/articles/uncertainty-is-intrinsic-to-the-human-cond...

https://news.cnrs.fr/articles/edgar-morin-in-praise-of-complex-thought