You are here

Has the current crisis changed our perception of science?

In France and around the world, the Covid-19 pandemic has dramatically focused public attention on the sciences with the mobilisation of researchers playing a decisive role. Called upon by both the media and government authorities, they have been highly active in providing information, and at times correcting misconceptions. In some cases, this crisis communication has been an opportunity for a much-awaited renewal, in particular concerning the presence of women in the media. In an interview on the public radio channel France Culture, the virologist Anne Goffard emphasised that the pandemic, more so than previous ones, has made it possible to see “women working as department heads in public and university hospitals, acting as spokespersons and showing that they are in charge”. “It is important for us, and also for the younger generation,” she said.1

While no one doubts just how exceptional this visibility is, the consequences are now the object of diverging, if not contradictory, assessments. To sum up the debate in bold strokes, some see the current pandemic as a show of force (in terms of mobilising resources, data production, discoveries, publications, etc.) that in the long run will inevitably boost public esteem for and trust in the scientific community. The others, conversely, believe the coronavirus crisis is tarnishing the image of science, by suddenly revealing that researchers and physicians do not always see eye to eye, and even more fundamentally, by disclosing the extent of the uncertainties inherent to scientific work. According to them, this can only undermine the public’s confidence in science.

Until now, the defenders of these two hypotheses have been able to draw upon the contradictory signals coming from the few available opinion polls. Studies by the Pew Research Center2 and Wissenschaft im Dialog3 have shown a significant increase in public trust with a 20-point and 10-point rise in Germany and the US, respectively, between 2019 and 2020. In France, on the contrary, the sparse available data is cause for caution, if not pessimism. An Ipsos-CEVIPOF survey on the French public’s attitudes in the context of Covid-19 showed a 10-point drop in confidence during April, down from a normally high level of about 85%. Some journalists and commentators are already proclaiming a kind of “French exceptionalism” reflected in a distrust of scientists.4 In an attempt to get a clearer picture of the situation in France, I decided – with the help of two colleagues – to launch a specific survey, which was then submitted to the Covid-19 Barometer.5 This “citizen science initiative” publishes a weekly online inquiry by Ipsos, based on a sampling of 5,000 people representative of the population of mainland France, aged 18 and older, and established using the quota method (gender, age, socio-professional group, region and urban category). As part of a “topical” module, a series of questions on the image of science was posted between 26-31 May. Without seeking to present all of the results from the questionnaire, three points deserve a closer look.

Stability of attitudes

The first key point from the survey, and certainly the most encouraging for the scientific community, i.e. that attitudes toward the sciences in France have been largely stable over time, confirms what was observed during previous health crises. Two questions were asked to ascertain the evolution of public trust during the epidemic. One focused on science as an institution: “Given the state of knowledge on coronavirus, would you say that you have more, less, or neither more nor less faith in science than before?” The other concerned the researchers themselves, with respondents being asked whether they now had “more, less, or the same level of confidence in scientists”.

Considering the intensive media exposure of certain personalities, especially current or former members of scientific councils, it seemed appropriate to dissociate the institution from the people behind its day-to-day operations. But in fact these nuances have no effect. Regardless of how the question is formulated, the predominant opinion remains that the current crisis has no impact on the public’s trust in the scientific community. In all, 77% of those sampled have “neither more nor less confidence” in science than they previously did. This result could be seen as relatively disappointing for those who had hoped for a spike in popularity commensurate with researchers’ commitment during the epidemic.

On the other hand, these figures will reassure those who feared growing distrust towards the sciences in France. Without getting into details, one encouraging fact is worth noting: among the sections of the population who reported a positive change of attitude, younger respondents, in the 18-29 age group, stand out with a slightly higher-than-average increase in confidence. This result is striking in that it belies the preconceived notion according to which young people – avid consumers of social networks and therefore widely exposed to more or less verified information – are often described as losing interest in science. It would seem that the current crisis, which has demonstrated the capacity of science not only to produce new discoveries but also to act as a structuring factor for social life, should in the long term encourage some youth to opt for a scientific career.

Long-standing ambivalence

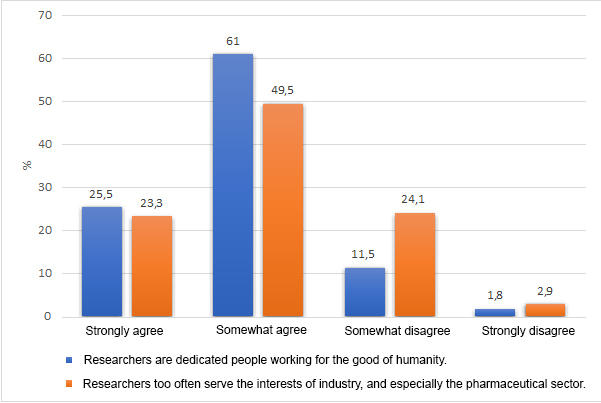

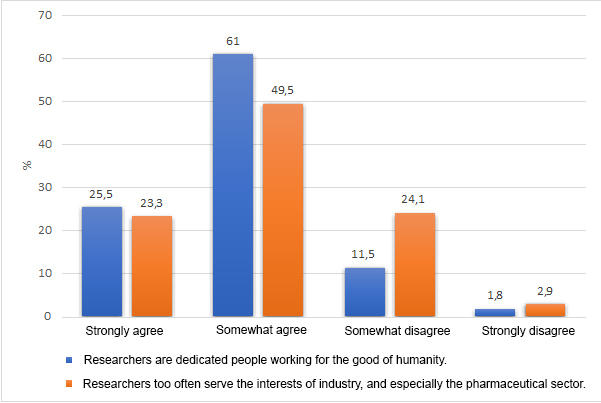

As major surveys conducted in France since the early 1970s have clearly shown, the expression of a high level of trust in science is usually accompanied by a marked ambivalence, not towards science itself, but towards its applications, whether real or imagined. The findings of the Covid-19 Barometer survey aptly illustrate this ambivalence, especially in the tendency of respondents to endorse certain apparently contradictory propositions. Some 86% of them agreed with the premise that “researchers are dedicated people working for the good of humanity”, but at the same time no fewer than 73% also believed that “researchers too often serve the interests of industry, and especially the pharmaceutical sector”.

The conflicting notions of dedication and profit are nothing new, but the pandemic has made them even more blatant. A number of journalistic investigations6 have used Transparence-Santé,7 a public database created in the wake of the Mediator-Servier affair, to illustrate the complexity of the links between experts and the healthcare industry, at times feeding the widespread suspicion that the former are not entirely independent. Our survey suggests that this feeling is firmly rooted in public opinion, and calls for substantive work on the part of both the scientific community and industry – especially the pharmaceutical sector. It is equally interesting to note that mistrust is not shared evenly, depending on the respondents’ self-declared political leanings. The proportion of those sampled who place themselves at the extreme left or right of the political spectrum express a level of doubt that is respectively 5 and nearly 10 points higher than the average. On the other hand, this ideological variation in the suspicion surrounding scientific independence is not observed in the responses concerning the value of dedication.

Exceptional measures

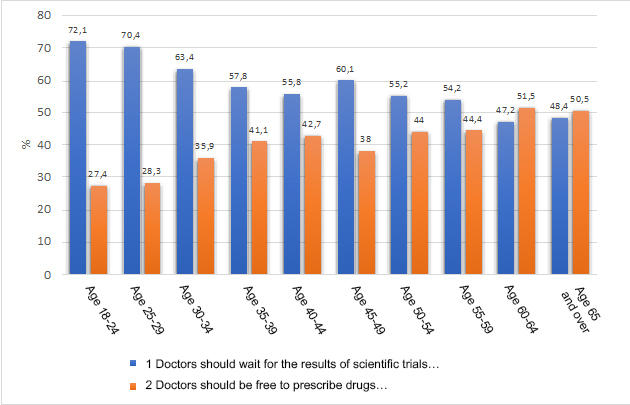

The third important point to emerge from this survey – the temptation to authorise emergency measures that pit the ethics of medical treatment against strict compliance with the rules and standards of scientific integrity – may explain the polarisation of the debate in France. As was the case during previous epidemics, such as HIV/AIDS, the coronavirus crisis has mobilised many players in and out of the scientific field, including politicians, in an attempt to speed up the public dissemination of unverified results. As emphasised in a recent issue of Science, this emergency approach exerts tremendous pressure on the necessary duration of research and poses substantial problems: “Early-phase studies have been launched before completion of investigations that would normally be required to warrant further development, and treatment trials have used strategies that are easy to implement but unlikely to yield unbiased effect estimates. Numerous tests investigating similar hypotheses risk overlapping, and droves of research papers have been rushed to preprint servers, essentially outsourcing peer review to practicing physicians and journalists.”8 In order to assess public opinion’s awareness of the dichotomy between the ethics of treatment and compliance with scientific integrity, the survey asked respondents to choose between two opinions: one stating that “doctors should wait for the results of scientific trials before administering drugs that could prove effective against the virus”, and another according to which “doctors should be free to prescribe drugs that could possibly combat the pathogen even if their effectiveness has not been scientifically proven”. Although the first viewpoint, not surprisingly, won majority approval with a decisive 57%, the emergency measures rationale appealed to nearly 42% of the sample population, with only 1% expressing “no opinion”.

As shown in Figure 2, the inquiry reveals significant variations of opinion depending on the respondents’ age. The 18-29 group seems to agree on scrupulous compliance with scientific methodology, while those aged 60 and over, who are at greater risk from the virus, are more amenable to granting physicians the freedom to use a treatment that might not be officially approved. Ultimately, this is still far from the broad public consensus that some have used as an excuse to try and justify the recourse to a therapy that is still in the evaluation phase. However, this result should prompt the scientific community, in particular France’s network of research integrity officers,9 to reflect on the lessons to be drawn from the coronavirus crisis, as well as on forthcoming communication initiatives aimed at both researchers and the general public.

The author is solely responsible for the points of view, opinions and analyses expressed in this article, which do not in any way constitute a statement of position by the CNRS.

- 1. La Méthode Scientifique, France Culture, 21 May 2020.

- 2. Funk, Cary; Tyson, Alec, “Partisan Differences over the Pandemic Response Are Growing”, Scientific American, 30 May 2020.

- 3. https://www.wissenschaft-im-dialog.de/en/our-projects/science-barometer/...

- 4. Matthew, David, “French trust in science drops as coronavirus backlash begins”, Times Higher Education, 9 June 2020 // Erner, Guillaume, La science, de l’incertitude à la defiance, France Culture radio station, 9 June 2020, https://www.franceculture.fr/emissions/linvite-des-matins/la-science-de-...

- 5. This survey was conducted jointly with Daniel Boy (Fondation nationale des sciences politiques) and Suzanne de Cheveigné (CNRS). The Covid-19 Barometer questionnaire is divided into two distinct parts: one consisting of a series of questions for monitoring the evolution of behaviours (e.g. observance of social distancing, time spent outside the home) and perceptions (e.g. perception of the severity of the pandemic, of risk to oneself, and to family and friends), and another part comprising “topical” modules addressing various topics. The results are accessible at https://datacovid.org/

- 6. Le Saint, Rozenn; Rouget, Antton, Covid-19: Les conseillers du pouvoir face au conflit d’intérêt, Médiapart, 31 March 2020.

- 7. A database created to make available all information declared by businesses concerning their financial links with the healthcare sector. The database is accessible at https://transparence.sante.gouv.fr/ A more user-friendly version can be accessed at https://www.eurosfordocs.fr/

- 8. London, Alex; Kimmelman, Jonathan, “Against pandemic research exceptionalism”, Science, 1 May 2020.

- 9. For more information on the “RESINT” network, see https://www.hceres.fr/en/news/resint-publishes-its-guide-recording-and-p...