You are here

Mont Saint Michel Reveals New Secrets

It is one of the world’ most famous landmarks. Every year, 2.5 million visitors storm the Mont Saint Michel, a tidal island off the coast of Normandy and a protected historical monument since 1874. Yet despite its seemingly homogenous architecture, the abbey, which was founded in the 8th century by Aubert, Bishop of Avranches, and became a powerful Benedictine monastery in the 10th century, is a structural kaleidoscope. It took more than a thousand years, and layer upon layer of constructions, demolitions and reconstructions to make it what it is today—a historical conundrum! However, it was only two decades ago that scientists, mainly historians and archaeologists, began to explore the monument dedicated to Saint Michael the Archangel.

“For a long time, we presumed that the history of the Mont Saint Michel had all been written,” notes Yves Gallet, professor of medieval art history at the Université Bordeaux-Montaigne. “In the 17th century, the monks of the Congregation of Saint Maur, who had just settled there, retraced the entire history of the site since its founding. This manuscript, published in the 19th century, was an especially precious resource because the monks had access to medieval archives that have since been destroyed during the 1944 bombing of Saint Lô, in Normandy.” In the late 1990s, the decision was made to restore the maritime character of the Mont Saint Michel, and a large-scale refurbishment project was launched, rekindling interest in the monument and leading to the first new scientific discoveries.

The enigma of the early Christian church

The Chapelle Notre Dame Sous Terre (the Underground Chapel of Our Lady), open to visitors only on rare guided tours, is one of the island’s most intriguing features. “Everyone agrees that it is the oldest part of the monastery, with its brick walls typical of buildings from the first millennium,” archaeologist Christian Sapin recounts. “But was it the early Christian church erected in the 8th century, or a construction from the 9th or 10th centuries?” A specialist in medieval architecture at the ARTEHIS1 laboratory, Sapin dated parts of the edifice—the first such studies ever conducted on the site. The hundred or so bricks analyzed in the 2000s using three different techniques—carbon-14FermerUsed only for organic materials, carbon-14 makes it possible to date the charcoal encased in the ancient mortar., archaeomagnetismFermerBy analyzing the magnetite in the clay, archaeomagnetism can determine the exact orientation and amplitude of the Earth’s magnetic field at the time when the bricks were fired. and thermoluminescenceFermerThermoluminescence is used to determine the amount of time elapsed since crystals, like these small pieces of quartz, were encased in earthenware., carried out jointly with the IRAMAT2 —revealed that the double-naved chapel was built partly in the first half of the 10th century and partly in the second half. Therefore, it cannot have been Aubert’s original church.

“The most probable hypothesis is that a large room was built originally, in the early 10th century, and the two barrel-vaulted naves were later additions, no doubt by the first monks,” Sapin believes. In the autumn of 2016, a joint project with the laboratory METIS3 relied on ground-penetrating radar (GPR, or georadar), a technology normally used by geologists to probe the subsurface, to determine that there was no previous construction below the level of Notre Dame Sous Terre. The site’s earliest Christian church thus continues to elude researchers…

On the Mont Saint Michel, even the names of the edifices can be confusing. “Notre Dame Sous Terre” gives the impression that the chapel was dug out deep within the rock outcropping, and indeed it does now lie at the bottom of a series of steps. “However, it was originally an exterior construction, built against the rock wall,” explains Florence Margo, a PhD student at the laboratory Archéologie et Archéométrie.4 “Later, other structures were erected all around the chapel, creating the illusion of its being ‘buried’.”

Georadar to profile the abbey church

Perhaps the most impressive of the many architectural wonders of the Mont Saint Michel is the magnificent abbey church that stands at its peak, dating back to the 11th century after the founding of the Benedictine monastery—even though the rock bed at the hilltop does not exceed 10 meters in length. “Three crypts were built around the summit to provide, along with Notre Dame Sous Terre, the foundation needed to erect the abbey church above them,” Margo explains.

One of them, the Crypt of the Massive Pillars, has long been a source of fascination for researchers. “In 1421 the choir of the Roman church collapsed and, with it, a part of its supporting crypt,” Gallet recounts. “Later in that century, both the chancel and what we call the Crypt of the Massive Pillars were rebuilt in the purest Gothic style.” However, the Roman remnants in the crypt led the historian to question the actual age of the granite columns. “The form and appearance of the Gothic choir just above it got me thinking,” he says. “Although it is in the flamboyant style typical of the 15th century, it has the layout of older Rayonnant churches, like Évreux Cathedral, which is 200 years older.”

Gallet surmises that some of the pillars of the Romanesque choir withstood the collapse and were “sheathed” (reinforced) to bear the weight of the Gothic chancel, whose walls rise higher than the previous Roman structure. In order to align the church’s colonnades with those of the crypt, its layout was modeled after an older building. This hypothesis was corroborated by a GPR study in the autumn of 2016: “The probes revealed the presence of a core of different stone inside the Gothic pillars,” Gallet reports.

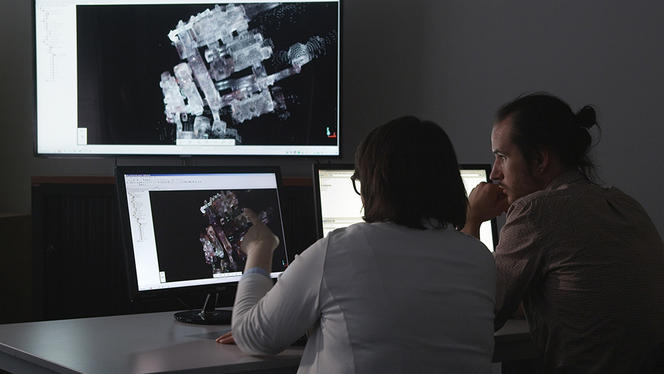

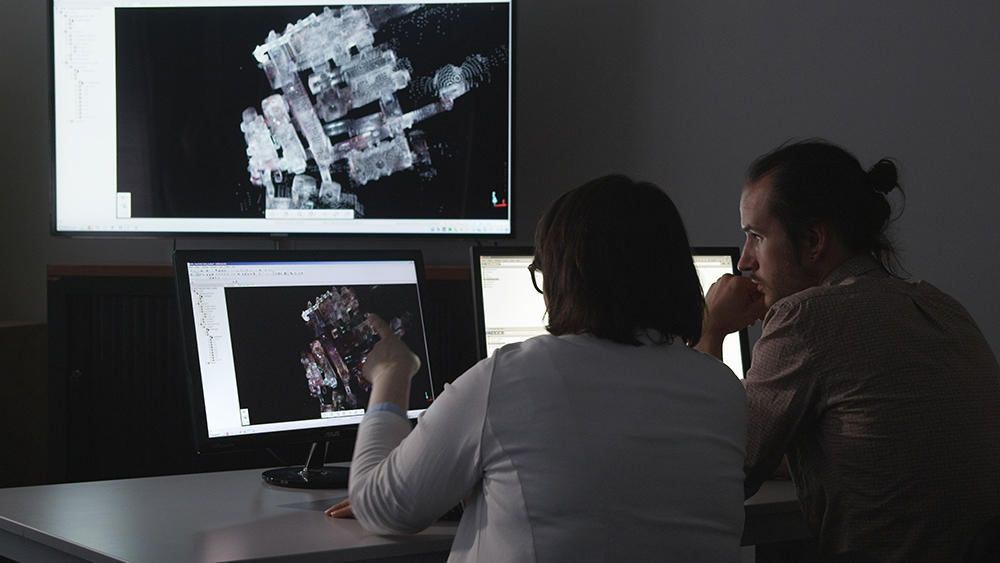

Modeling the abbey in 3D

The organization of the monastery itself continues to raise questions: where were the pilgrims accommodated? Where were the friars’ living quarters? According to Margo, “in theory, Saint Benedict’s stringent rules forbade the monks from having any contact with outsiders or worshippers, and all of the Order’s abbeys followed a similar floor plan. In this case, however, severe topographic restrictions meant the abbey had to be erected upwards, which makes it difficult to interpret its different spaces.” Add to this the site’s history of structural failures, like the collapse in the 18th century of the building housing the kitchens, and the various extensions built over time—including the spectacular “Marvel” and its two three-story buildings clinging to the north side of the rock since the 13th century—and any analysis becomes a seemingly impossible feat.

A 3D scan of the abbey using photogrammetryFermerPhotogrammetry analyzes the redundancy between thousands of photographs taken from different angles (with a minimum overlap of 80%) to render the contours of the site and recreate the buildings in 3D., carried out in the winter of 2016, provided a better understanding of the building’s circulation paths. “The 3D model made it possible to determine the connections among the passageways from the Romanesque period, hidden inside the thick walls, some of which opened out to a void,” Margo says. “My hypothesis is that they linked the kitchen building, which is no longer there, to the monks’ dining hall, making it possible to circumvent other living areas.”

Each renovation yields new discoveries

In addition to research on the accessible parts of the buildings, numerous excavations by the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) over the past 20 years have also yielded their share of discoveries. “Since 1997, we have been involved every time new works start at the Mont Saint Michel,” reports François Caligny Delahaye, who supervised the INRAP’s excavation projects from 2002 to 2015. “This encompasses restorations, like the reinforcement of the ramparts in preparation for the rehabilitation of the site’s maritime character, refurbishments of the abbey to improve public access, weatherproofing such as that carried out in the cloister between January and November 2017, and roadworks including those scheduled for 2015 to 2022 to renovate the utility networks (wastewater, electricity, etc.) in the main street.”

The first excavation revealed the surprising complexity of the walls surrounding the Mont Saint Michel. “Despite the outward uniformity provided by the machiocolations that were added in the 15th century, the ramparts visible today were built over a period that spanned the 13th to the 18th centuries,” Caligny Delahaye says. “The first defensive wall, from the 13th century, stood at the level of the village church, Eglise Saint Pierre, where a gate had been built. Only the section on the northern side of the island, facing the sea, has been preserved. A second rudimentary enclosure was erected at the foot of the hill in the 14th century and reinforced in the 15th century during the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453).”

Because of the English occupation of Tombelaine, an island northeast of the Mont Saint Michel, a gate in the ramparts on the east side of the hill was blocked by a tower (the gate, which had long been mistaken for a simple vault, can be seen in the cellars of a restaurant) and the site’s economic center moved. “During the 13th and 14th centuries, the core of the village, with its many shops, was most likely located high on the rock,” the archaeologist explains. “But starting in the Hundred Years’ War, it gradually shifted to the foot of the hill, where it is today.”

Unearthing a medieval necropolis

Another notable finding was that of a badge workshop from the 14th and 15th centuries, near the entrance to the abbey. “The renovation, which began after a tree fell on the terrace walls during the windstorm of 1999, revealed fragments of stone molds used to cast pilgrimage badges, brought back as ‘souvenirs’ by the pilgrims of the time,” Caligny Delahaye recounts. “They were found depicting the archangel Saint Michael, the Virgin Mary, the famous Saint James scallop shell, pilgrim’s horns, etc.” Proof that making a thriving business out of visitors to the site is nothing new!

“At the Mont Saint Michel, there’s a surprise behind every stone,” confirms Elen Esnault, who is now in charge of the INRAP’s preventive excavations. Last year was especially fruitful. The weatherproofing of the cloister allowed researchers to unearth the old paving from the 13th century, 40 centimeters below the current floor level. Yet the most amazing discovery was made under the village’s main street, during the works on utility lines: three dozen medieval graves were brought to light! “We knew that there had been a cemetery around the church, part of which had been abandoned after the 13th-century ramparts were built,” the archaeologist explains. “Still, we were not expecting to find this. Some of the graves are intact and we could identify men, women, and probably children—the earliest known inhabitants of the Mont Saint Michel.”

When did these people live? What pathologies afflicted them? “We should be able to find out before the end of 2018, after the INRAP anthropologists complete their carbon-14 analyses and health diagnoses,” Esnault says. In any case, the find is unprecedented, as scientists had never had access to the gravesites of the Mont Saint Michel until now. No doubt research on the island has a bright future.

___________________________________________________

Timeline

• 708: Aubert, Bishop of Avranches, founds a sanctuary dedicated to Saint Michael the Archangel. Beginning of the first pilgrimages.

• 965: Founding of the Benedictine monastery.

• 1020-1180: Construction of the Romanesque abbey.

• 1204: King Philip Augustus takes possession of the Mont Saint Michel, previously the property of the Duchy of Normandy.

• 1204-28: Construction of La Merveille (“The Marvel”), topped by the cloister.

• 1337-1453: The English try to seize the island during the Hundred Years’ War.

• 1789: The site becomes state property and is converted into a prison.

• 1864: The Mont Saint Michel becomes a protected historical monument.

- 1. Laboratoire Archéologie, Terre, Histoire, Sociétés (CNRS / Inrap / Université de Bourgogne).

- 2. Institut de Recherche sur les Archéomatériaux (CNRS / Université d’Orléans / Université Bordeaux Montaigne / Université de technologie Belfort-Montbéliard).

- 3. Milieux Environnementaux, Transferts et Interactions dans les Hydrosystèmes et les Sols (CNRS / UPMC / EPHE).

- 4. CNRS / Université Lumière Lyon 2 / Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1.