You are here

And then Came Agriculture

Around 8500 years ago, populations from the Middle East arrived in Greece and southern Bulgaria. They brought with them seeds of wheat, barley and other edible plants. They were accompanied by curious animals that, rather than fleeing humans, followed them docilely. Without realizing it, these migrants on the lookout for a place to settle were to trigger one of the most fascinating upheavals ever to affect Europe: the introduction of farming and herding.

A transition, known as Neolithization, then got underway: the Mesolithic gave way to the Neolithic, and a Europe of farmers replaced the communities who lived by hunting, fishing and foraging. This change was accompanied by a profound cultural transformation that completely overturned the former system of belief.

A period of cultural transformation

It was through this cultural transformation that an international team decided to tackle the Neolithization of Europe. Led by CNRS researchers from the Center for International Research in the Humanities and Social Sciences (CIRHUS)1 and the PACEA laboratory,2 the team undertook a groundbreaking study of personal ornaments, such as necklaces, pendants and other adornments.

ornaments to display cultural and social affiliation.

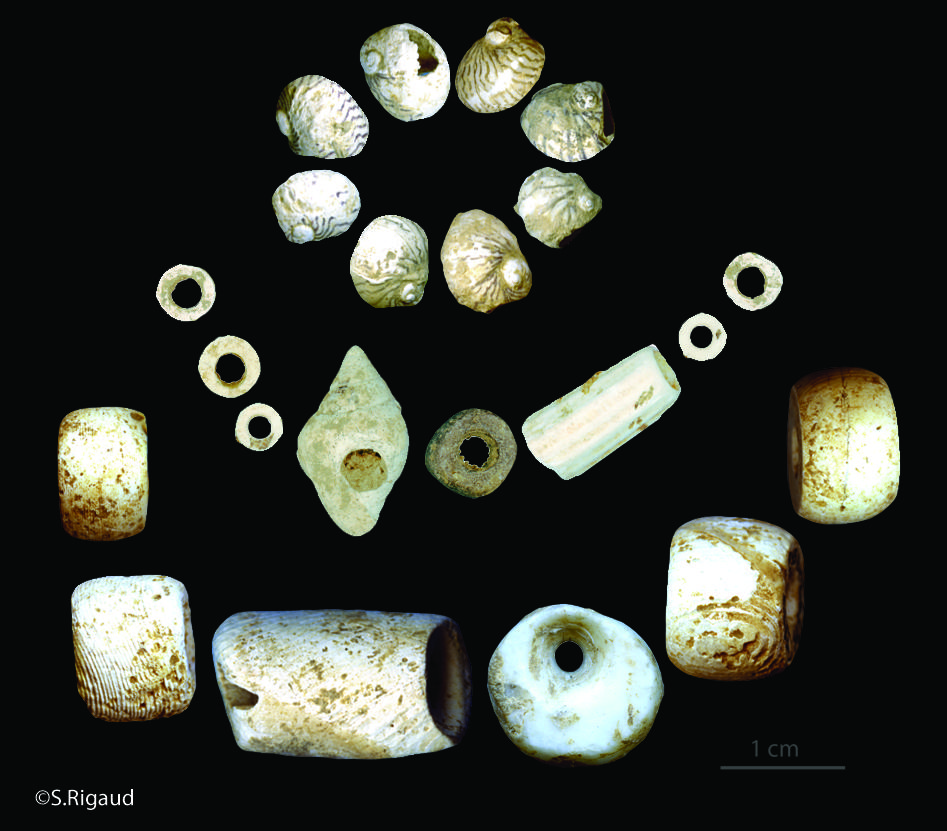

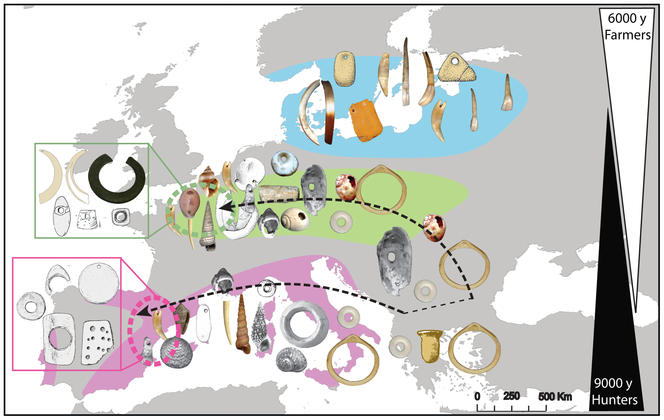

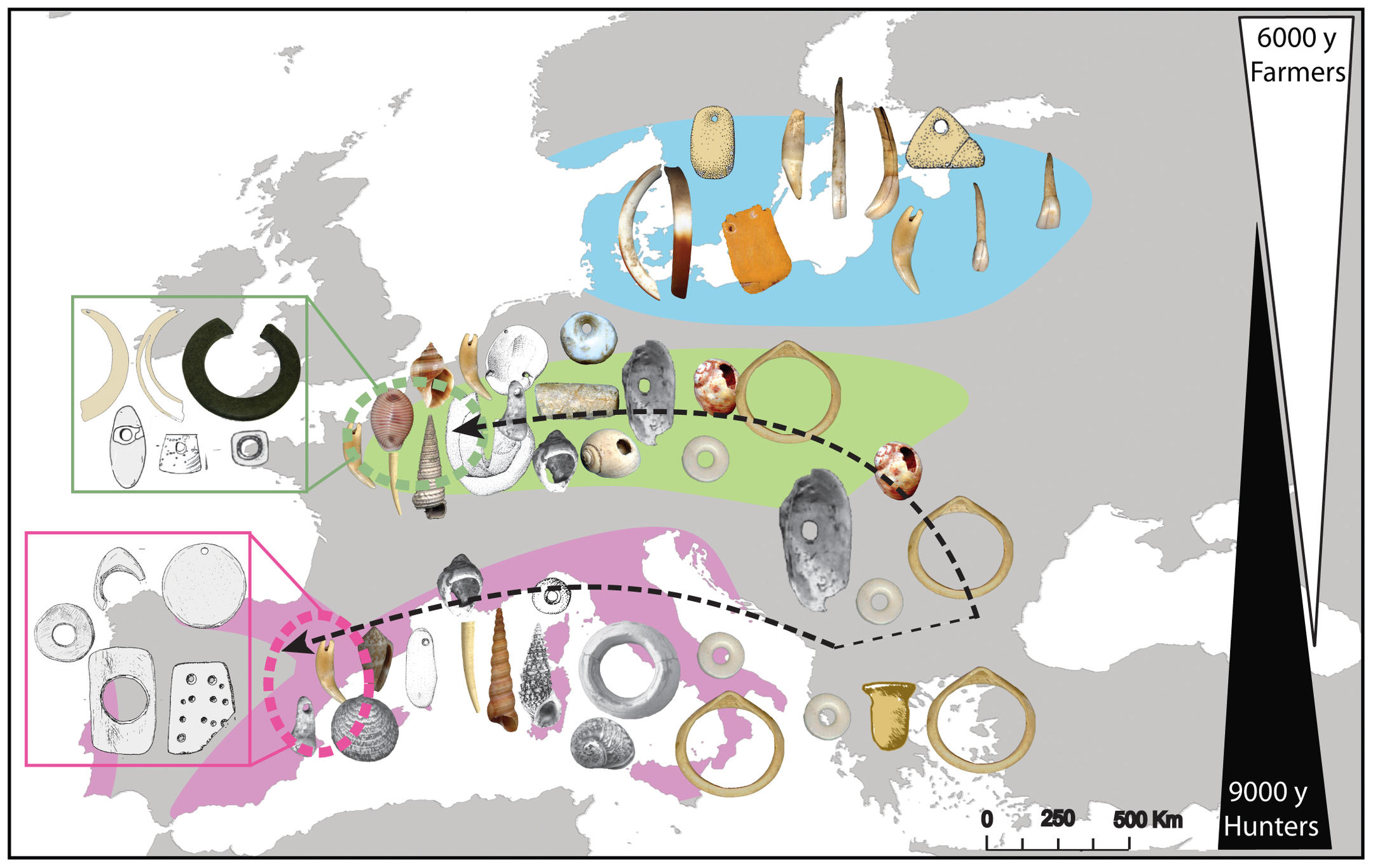

Why study ornaments? "In every society, they are used to convey a message about the cultural and social affiliation of the person wearing them. Such messages are only comprehensible to individuals who share the same values," explains Solange Rigaud, a researcher at CIRHUS. Personal ornaments therefore reflect the cultural transition associated with Neolithization. Mesolithic hunter-gatherers traditionally wore teeth from red deer, wild boar and other mammals, shells and small, perforated pebbles. But then the farmers gradually started to become dominant. Unlike the hunter-gatherers, they preferred ornaments made of tubular, flat or spherical beads that they cut and polished from minerals, bones and shells.

In this study, published in Plos One on April 8, 2015, the researchers listed 224 bead types from 437 archaeological sites of 48 different Mesolithic and Neolithic cultures throughout Europe. Analysis of these ornaments, dated at 8000 to 5000 years old, and of their geographical distribution revealed not only the progress of agriculture but also its stumbling blocks. In fact, the conquest of Europe by farmers was not a uniform, linear process. Ornaments show in particular that acceptation of this new way of life varied considerably between North and South. In the Mediterranean region and central Europe, Neolithization asserted itself relatively quickly. In northern Europe, however, the populations hardly changed their way of life, as testified by their refusal to accept any new type of personal ornament. For several centuries, the peoples of the Baltic resisted Neolithization.

Agriculture spreads in fits and starts

In the 1970s, many prehistorians thought that agriculture had spread inexorably across Europe as an advancing front. They even calculated its rate of progress: one kilometer per year, or 25 kilometers per generation. According to their model, the indigenous peoples disappeared and were replaced by populations from the Near East.

This hypothesis is today widely disputed. Researchers now believe that the introduction of farming took place in fits and starts, with sudden advances, periods of stagnation, and even retreats. Moreover, genetic data shows that the original inhabitants, far from disappearing, gradually became incorporated into these new societies, or else adopted Neolithic innovations of their own accord.

Analysis of personal ornaments strongly supports this new scenario. It shows both that the spread of farming took place at very different rates, particularly between northern and southern Europe, and that the different cultures were in close contact. In many Neolithic sites, ornaments characteristic of farmers and of hunter-gatherers are found in the same archaeological layers, which is evidence that these populations maintained complex relations.

There are several reasons why Neolithization was so slow in Europe. "The newcomers did not land in uninhabited regions: they had to deal with the local populations. Furthermore, they had not yet mastered agriculture: they needed to understand the seasons at these latitudes and find appropriate agricultural varieties. There are indeed traces of setbacks marked by large population fluctuations in the early Neolithic," Rigaud explains. The hunter-gatherer populations, on the other hand, knew how to take full advantage of their environment. The adoption of the Neolithic way of life, which finally became dominant, was probably governed by new belief systems. Changes in personal ornaments reflected these changes symbolically.

Genetics and linguistics to the rescue

A host of questions remain unanswered. For example, it is not known whether Indo-European languages arrived at that time, whether they had already been present since the resettlement of Europe following the last deglaciation period,or if they spread later in the Bronze Age. Similarly, scientists are only just beginning to elucidate the imprint left by Neolithization on the genetic pool of modern European populations and distinguish it from the imprint of subsequent waves of settlement.

Rigaud believes that the inventory and analysis of personal ornaments carried out in this study will help to provide new answers. "Our approach is similar to that of geneticists and linguists. It enables us to find a common language and ground, and conduct interdisciplinary studies that are seldom carried out in archaeology." For instance, the researchers are hoping to compare their record of ornaments with genetic and anatomic datasets, as well as with models of language dissemination. This could make it possible to find out whether the cultural changes reflected by ornaments correspond to changes in other areas—and to what extent.