You are here

Rethinking the Origin of Dogs

Tracing the history of dog domestication is key for fundamental research, and a topic that requires multiple perspectives, as illustrated by a new international study1 uniting zooarchaeologists and paleogeneticists. Headed by a team at Oxford University (UK), this research inolved three French laboratories.2

“Exploring this subject sheds light on human evolution, as the history of the canine race is part of our own,” explains Anne Tresset,3 a Paris-based zooarchaeologistFermerZooarchaeology seeks to retrace the history of the natural and cultural relations between humans and animals. and co-author of the study. Dogs are indeed the first animals to have been domesticated by man—“they have lived in human societies since the end of the Upper Paleolithic, in other words for at least 15,000 years,” she points out. “In comparison, the domestication of cattle, sheep, goats and pigs began several thousand years later, during the Neolithic period, some 10,500 years ago.” In addition, the dog enjoys a special status: “It’s man’s best friend, and probably always has been,” the researcher adds. “For example, we have found dog bones next to human remains in tombs of the Middle Eastern Natufian culture, which dates back to the Epipaleolithic, more than 11,000 years ago.”

More than one domestication

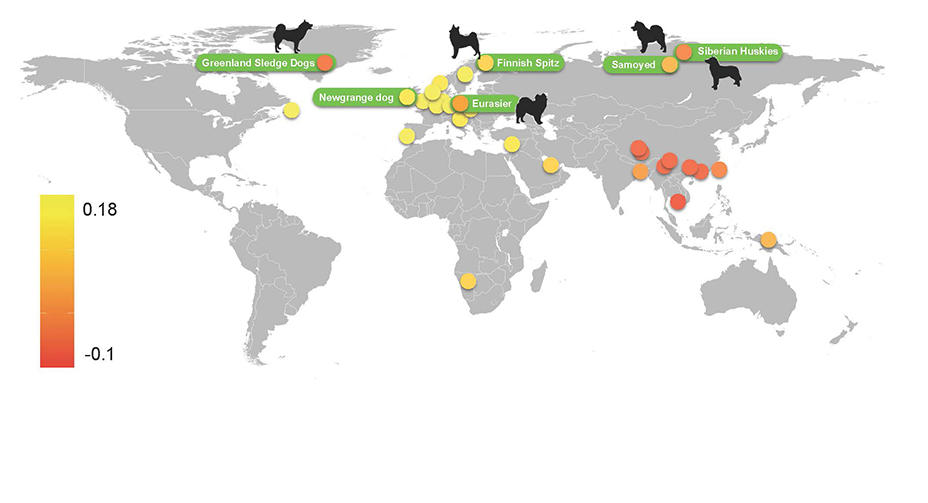

More precisely, the new study suggests that the dog is the result of not one but two independent domestications of wolves: one in Europe and the other in East Asia, at least 15,000 and 12,500 years ago, respectively. Then, between the 5th and 4th millennia BC, Asian dogs migrated to Europe, no doubt together with human populations, and interbred with European species. After that, their descendants gradually replaced the original breeds.

In fact, archaeozoologists have suspected for several decades that dogs have a dual origin, based on the study of ancient canine remains dated to the late Upper Paleolithic or Epipaleolithic. However, most geneticists remained convinced that there had only been a single domestication, and that it took place in Asia. With good reason: an analysis of the DNA of modern dogs shows that most of them belong to a set of specific genetic lineages of Asian origin, called haplogroup A. Yet, according to Tresset, “this approach reaches its limits when certain events—here, the arrival of Asian dogs in Europe—obliterate the gene pool predating the population being analyzed. This makes it impossible to ‘see’ what existed before, namely that there were domesticated dogs belonging to haplogroup C in Western Europe before the arrival of Asian dogs.”

Bones from the very first dogs!

“The strength of our new study is that it enabled us, for the first time, to analyze the DNA of many archaeological remains spanning a long period in the history of the dog, with the oldest ones dating back 14,000 years—i.e. the beginning of this mammal’s evolutionary history," points out the Lyon-based paleogeneticistFermerPaleogenetics (or paleogenomics) focuses on the genetic analysis of living beings from the past. Catherine Hänni.4 "In addition, our samples came from many different geographical areas in Europe (France, Switzerland, Germany, Romania…) and Asia (Iran, Turkmenistan, eastern Russia).”

In concrete terms, the researchers reconstructed canine evolutionary history by studying 59 archaeological remains of dogs that lived between 14,000 and 3,000 years ago. The process involved sampling the ancient DNA of these bones before sequencing their mitochondrial DNA (found in specific cellular organelles called mitochondria). The complete genome of a 4,800-year-old dog was also sequenced.

“These results would never have been possible without close cooperation between zooarchaeology, paleogenetics and genomic analysis,” Hänni enthuses.

A winning three-pronged collaboration

In practical terms, the archaeozoologists gave the other researchers access to the archaeological remains of dogs they had studied in previous projects. “Our team alone provided more than three-fourths of the samples that were analyzed,” Tresset reports. The paleogeneticists, including Hänni’s team in Lyon, subsequently extracted and sequenced the DNA from the bones. The Oxford team then took over and created a digital model based on the ancient genetic sequences and those of 2,500 previously-studied modern dogs, making it possible to reconstruct the canine evolutionary treeFermerSchematic showing the links of kinship between different groups of living beings..

To the researchers’ surprise, the model revealed a difference between the dogs originating from Asia and those from Europe, dating back to less than 14,000 years ago—i.e. after the appearance of dogs in Europe! This led the scientists to conclude that there were originally two distinct dog populations, one in Asia and one in Europe. The study yielded another important finding: the mitochondrial DNA analyses of modern and ancient dogs showed that, while most of the ancient European specimens belonged to haplogroup C (60%) or D (20%), the majority of modern-day ones are of haplogroups A (64%) and B (22%), both of Asian origin, pointing to a migration from Asia to Europe.

Other issues need solving

In the future, Tresset, Hänni and their teams hope to elucidate little known episodes in the European and Middle Eastern history of the dog. “For example, we would like to understand why small breeds are predominant in Western Europe and larger ones in Eastern Europe," the researcher says. "More generally, we’d like to study the factors underlying the evolution of their size, color and even body shape in the course of their history (selection by humans, etc.).” Best friends though they may be, our canine companions still harbor many secrets.

- 1. A. Frantz et al.,“Genomic and archaeological evidence suggest a dual origin of domestic dogs,” Science, 2016. 10.1126/science.aaf3161

- 2. PALGENE, Plate-forme Nationale de Paléogénétique (CNRS / ENS de Lyon), Institut de Génomique Fonctionnelle de Lyon (CNRS / ENS de Lyon / Université Lyon), Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine (CNRS / Université Joseph Fourier / Université de Savoie) ; “Archéozoologie, Archéobotanique, Sociétés, Pratiques, Environnements” (CNRS / MNHN); Institut de Génétique et Développement de Rennes (CNRS / Université de Rennes 1).

- 3. Archéozoologie, Archéobotanique, Sociétés, Pratiques, Environnements (CNRS / MNHN /)

- 4. PALGENE, Plate-forme Nationale de Paléogénétique (CNRS / ENS de Lyon), Institut de Génomique Fonctionnelle de Lyon (CNRS / ENS de Lyon / Université Lyon), Laboratoire d’Ecologie Alpine (CNRS / Université Joseph Fourier / Université de Savoie).

Explore more

Author

A freelance science journalist for ten years, Kheira Bettayeb specializes in the fields of medicine, biology, neuroscience, zoology, astronomy, physics and technology. She writes primarily for prominent national (France) magazines.