You are here

A century on, does BCG have a future?

It was a true health revolution that made its two initiators (almost) as famous as Pasteur himself. In July 1921, the first vaccine against tuberculosis was administered to a new-born infant at Hôpital de la Charité in Paris. BCG, or “Bacille Calmette-Guérin”, was born, named after a physician and a veterinarian working together at Institut Pasteur in Lille (northern France). Since then, four billion doses have been injected worldwide and prevented the deaths of millions of young children.

“Tuberculosis was one of the leading causes of infantile mortality,” recounts Olivier Neyrolles, microbiologist at the Institute of Pharmacology and Structural Biology (IPBS).1 “Unlike adults, who mostly develop pulmonary types of the disease, tuberculosis takes a disseminated form in children, and in particular meningitis which involves a very high death rate. The vaccine developed by Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin enabled a 95% reduction in fatalities.” More astonishing is the fact that physicians in those early years quickly realised that while the vaccine was undoubtedly effective against tuberculosis, it also protected children from other infectious diseases.

Millions of children saved

The efficacy of BCG in humans is particularly remarkable because it had initially been developed to protect…. farmed livestock. “The vaccine was developed against bovine tuberculosis, the strain of which differs slightly from that of human tuberculosis,” explains Camille Locht, microbiologist at the Lille-based Centre of Infection and Immunity (CIIL).2 “It worked so well in cattle, and the pressure was so great, that it was tested in children of tuberculous families with the success we now know.”

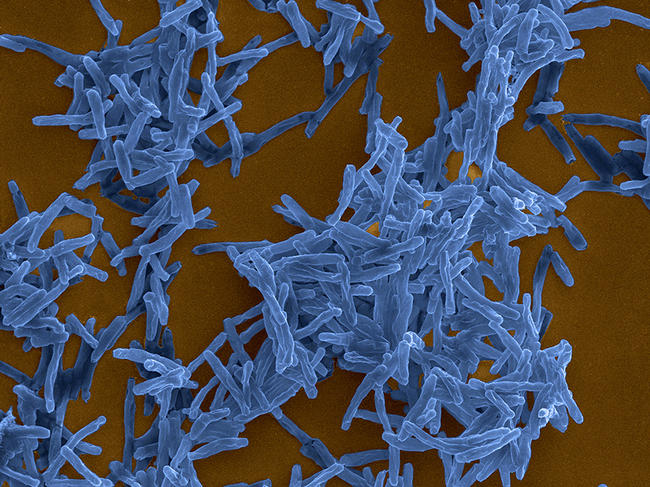

The technique employed is entirely derived from Pasteur’s methods using a live attenuated bacillus. Over 13 years, the bovine tuberculosis agent was replicated in vitro 230 times until it was deprived of all its virulence and presented no danger. “That is generally how pathogens evolve when they are no longer subject to any selection pressure,” the researcher says. “Since then, the complete genome of the attenuated bacillus has been sequenced, showing that it had lost entire parts of its DNA that were of particular importance to virulence.”

Although it has now been in circulation for a century – it is the oldest vaccine still in use – BCG has not yet succeeded in eradicating tuberculosis. Ten million people develop the disease each year, and nearly 1.5 million die from it (including 400,000 who are co-infected by HIV), which still makes it the most fatal infection in the world, with the exception of Covid-19. Highly effective in children, the Calmette and Guérin inoculation has in fact been shown to offer less protection against the pulmonary form of tuberculosis in adults, which although less lethal is much more contagious because it is spread by aerosols.

Tuberculosis – a formidable enemy

“Tuberculosis is a disease of poverty, and is particularly common in Africa and Asia, hence the relative lack of interest in developed countries. But as soon as deprivation reappears somewhere, TB is not far behind,” says Neyrolles, who points to crowded living conditions, a poor diet and insufficient access to healthcare as the principal factors for its emergence. In France, where between 5000 and 6000 cases are notified each year, the most severely affected areas are underprivileged suburbs in the Paris region.

TB is a formidable enemy – ten bacteria are sufficient to infect an individual – whose progression often goes unnoticed: a quarter of the world’s population may carry the pathogen without displaying any symptoms. “In 90% of cases, the immune system controls the infection and causes a small nodule in the lung, unbeknownst to those affected,” Neyrolles adds. “Five percent of patients develop the disease immediately, while in the remaining 5% tuberculosis may break out several years after contamination, generally at a time when the immune system has been weakened for a variety of reasons (fatigue, ageing, malnutrition, etc.).” The case of a man who became ill thirty years after being contaminated by his tuberculous father is well known in the medical sphere.

Both lengthy (a minimum of six months), and toxic, treatments sometimes struggle to deal with bacteria that have developed resistance to numerous antibiotics. “Only a vaccine that is really effective in adults will be able to overcome the epidemic,” insists Neyrolles. The scientific community has been working on this for some fifteen years, and several strategies are under study.

Towards a new vaccine against tuberculosis

“Some colleagues are redeveloping the Calmette and Guérin inoculation, using modern tools,” explains Locht. “They are producing a live attenuated bacillus from a human strain of tuberculosis that they have genetically modified by deleting specific genes thought to be involved in virulence.” Another strategy is to develop a cocktail of several antigens (the proteins in the pathogen that trigger the immune response) and combine them with an adjuvant. The use of viral vectors including chimpanzee adenovirus (as in the Oxford/Astra Zeneca vaccine against Covid-19) is also being considered; the messenger RNA technology, on the other hand, is not adapted to the tuberculosis bacillus.

Among the sixteen vaccine candidates under development, two are in phase 3 of their clinical trials and must now prove that they offer better protection than BCG, whose average efficacy in adults is estimated at 50%. “We all have Covid-19 in mind, insofar as it only took a few months to develop inoculations that are more than 90% effective,” Locht points out. “The famous Spike protein – situated on the surface of SARS-CoV-2 – was discovered and proved sufficient to trigger a powerful antibody response. Unfortunately, tuberculosis is a different story altogether in terms of complexity!”

First of all, this is because the pathogen contains not just six proteins like SARS-CoV-2, but nearly 4000, which are located both on the surface and inside the bacterium. Determining which to target in order to elicit a sufficient immune response remains a challenge for researchers. “To date, the scientific community has identified around a dozen proteins as being involved in triggering natural defences,” says Locht. “We are now looking at how they can be combined and presented to activate the immune system.”

The immunity conundrum

The second hurdle is that specialists are still struggling to understand the precise nature of the immunological reaction, and particularly the protective immune response, to the tuberculosis bacillus. Scientists are certain of just one thing: unlike what happens in the case of Covid-19, for example, where the production of antibodies (by B lymphocytes circulating in the blood) is sufficient to control the attack, the immunity activated against tuberculosis is essentially cellular and involves T lymphocytes, some of which reside at the heart of tissues. “As it happens, the T-cell response is very complex,” Locht notes. “There are several types of T lymphocytes, all operating in different ways. For example, we know that some are regulatory and can either reduce an infection or, on the contrary, enhance it. We have to make sure that we focus on the right target.”

The heterogeneity of the immune response in a single individual is also baffling to scientists. “In the same lung you may find that some areas are severely infected while others are totally unaffected,” explains Neyrolles. “This means that the defence mechanisms activated are not the same everywhere, which obviously complicates our task!”

A second life for BCG

Although undeniable progress has been achieved, developing an effective vaccine may still take years, and does not necessarily mean that BCG will disappear. Indeed, scientists have found surprising therapeutic applications for the Calmette and Guérin jab in the recent past.

“The BCG inoculation is currently the best drug we have to treat superficial bladder cancer,” Locht stresses. “In this case, it is injected directly into the tumour. It has also produced some interesting results in certain melanomas and in the treatment of type 1 diabetes.” The question is also whether it could be used to treat the infection caused by Sars-CoV-2, and some fifteen studies are underway to test its efficacy.

The therapeutic activity of the vaccine remains a mystery, although the experts have an idea. “It appears that BCG reinforces innate immunity,” Locht suggests. “In other words, the non-specific and rapid protection mechanism that constitutes our first line of defence. This is a very new and extremely exciting research area!”

Upcoming events - 6th Global Forum on TB Vaccines, Toulouse, postponed from April 2021 to February 2022 (precise dates not available) - Symposium on BCG and its therapeutic uses, Institut Pasteur de Lille, 17-19 November 2021