You are here

Emerging Technologies to Fight Alzheimer’s

It is one of the most striking achievements of the modern world, and one that everybody can benefit from, at least in theory: across the planet, people live longer. In the last century, global life expectancy has more than doubled, largely due to medical progress and improved sanitation. This extended lifespan means that in many countries, the elderly make up the fastest-growing category. New challenges are emerging as society comes to grips with the issues facing an ageing population, including a proliferation of age-related illnesses, such as Alzheimer’s. To improve diagnosis and aids, forward-thinking CNRS researchers from the Knowledge, Information and Web Intelligence (KIWI),1 Applied Research for (multi)Media Enrichment, Diffusion, Interaction and Analysis (ARMEDIA),2 and ACMES3 teams are developing state-of-the-art tools based on information and communication technologies.

Early diagnosis, but how?

Alzheimer’s is the most common form of dementia. Mainly affecting people aged 65 and over, it develops as clumps and tangles form in brain fibers, and connections between neurons are lost, eventually leading to the death of brain cells. Patients risk gradually losing their memory, thinking and reasoning skills until they are wholly dependent on caregivers.

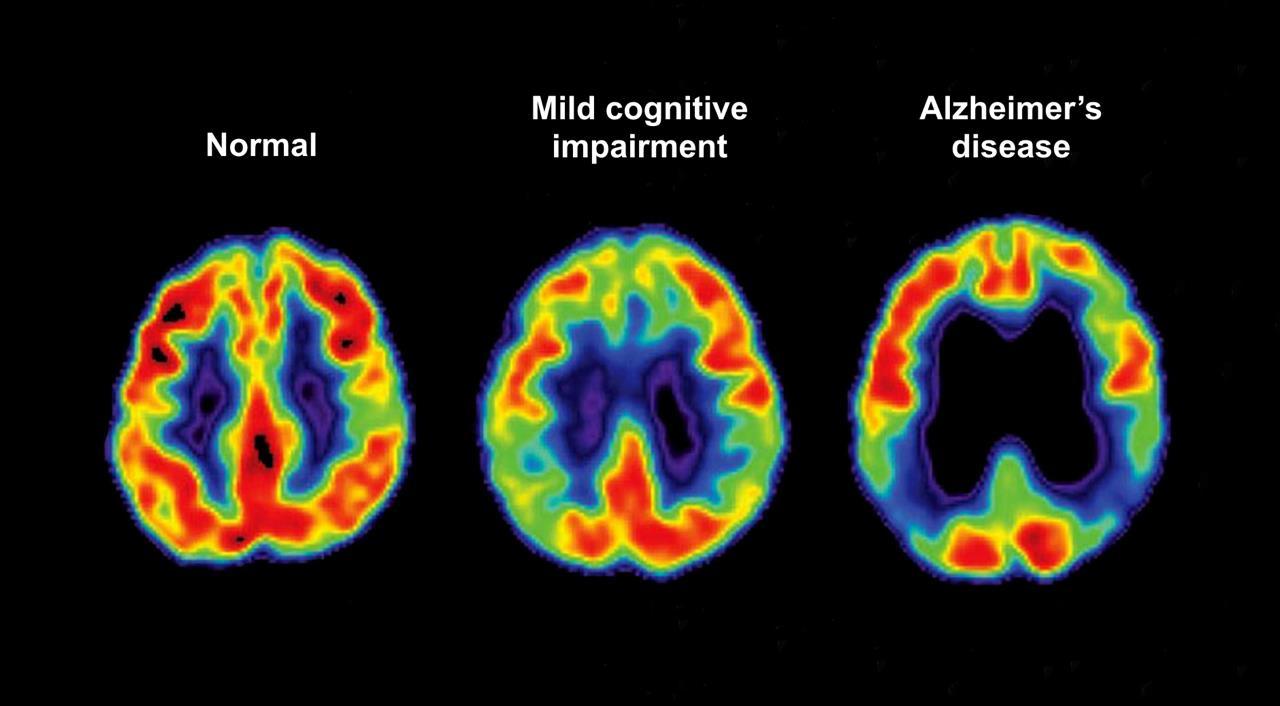

One of the first challenges raised by Alzheimer’s is diagnosis. Imaging techniques like magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can show the brain abnormalities that it causes, including atrophy. However, it is not easy to determine whether a scan is necessary in the first place, nor tell an Alzheimer’s sufferer from an elderly person with a “normal” level of forgetfulness. Difficulty in recognizing the illness means that many sufferers remain undiagnosed. In the US alone, while an estimated one out of nine 65 year-olds and over had Alzheimer’s in 2015, only half had been informed of their condition.4 Yet early diagnosis is crucial to stimulate patients and help them maintain their cognitive skills as long as possible.

The need for simple diagnosis methods has notably inspired two separate CNRS teams. Based in Lorraine (northeastern France), the KIWI team focuses on to adapting computer-system services to user requirements or preferences. This has led it to address the issue of identifying sufferers of neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s, given that the actions of computer users (for example, clicks or pages visited) in reaction to onscreen data largely depend on their memory capacity.

Through its exploration of user actions and memory, KIWI has digitized common neuropsychological tests for assessing the relationship between the brain and behavior, until now only available in paper form. These include the Trail Making Test, which requires a user to connect dots quickly and accurately. Designing tests appropriate for the target users—elderly subjects “untrained in computers and potentially suffering from physical restrictions, whether visual or mobility-related”—was particularly challenging, notes KIWI computer scientist Sylvain Castagnos. Yet the digitization of conventional tests enabled researchers to have access to “a reliable automated system” that eliminates human error in the collection of data.

The KIWI's method also improves on the classic tests on paper by integrating other approaches. In particular, it includes an oculometer to track eye direction, thus making it possible to detect “potential links between atypical eye movements or gestures, and Alzheimer’s,” says Castagnos. Eventually, the scientists also intend to use the oculometer to “stimulate patients via brain exercises aimed at delaying the progress of the disease.”

In collaboration with the geriatric unit of the Nancy University Hospital in northeastern France, KIWI researchers are collecting data from different populations—Alzheimer’s sufferers; memory-challenged non-sufferers; and healthy individuals—to single out the factors most likely to indicate the patient’s pathology. The next stage will be to produce mathematical models that can “analyze user traces in real time and offer early diagnosis of the illness.”

A window to the mind

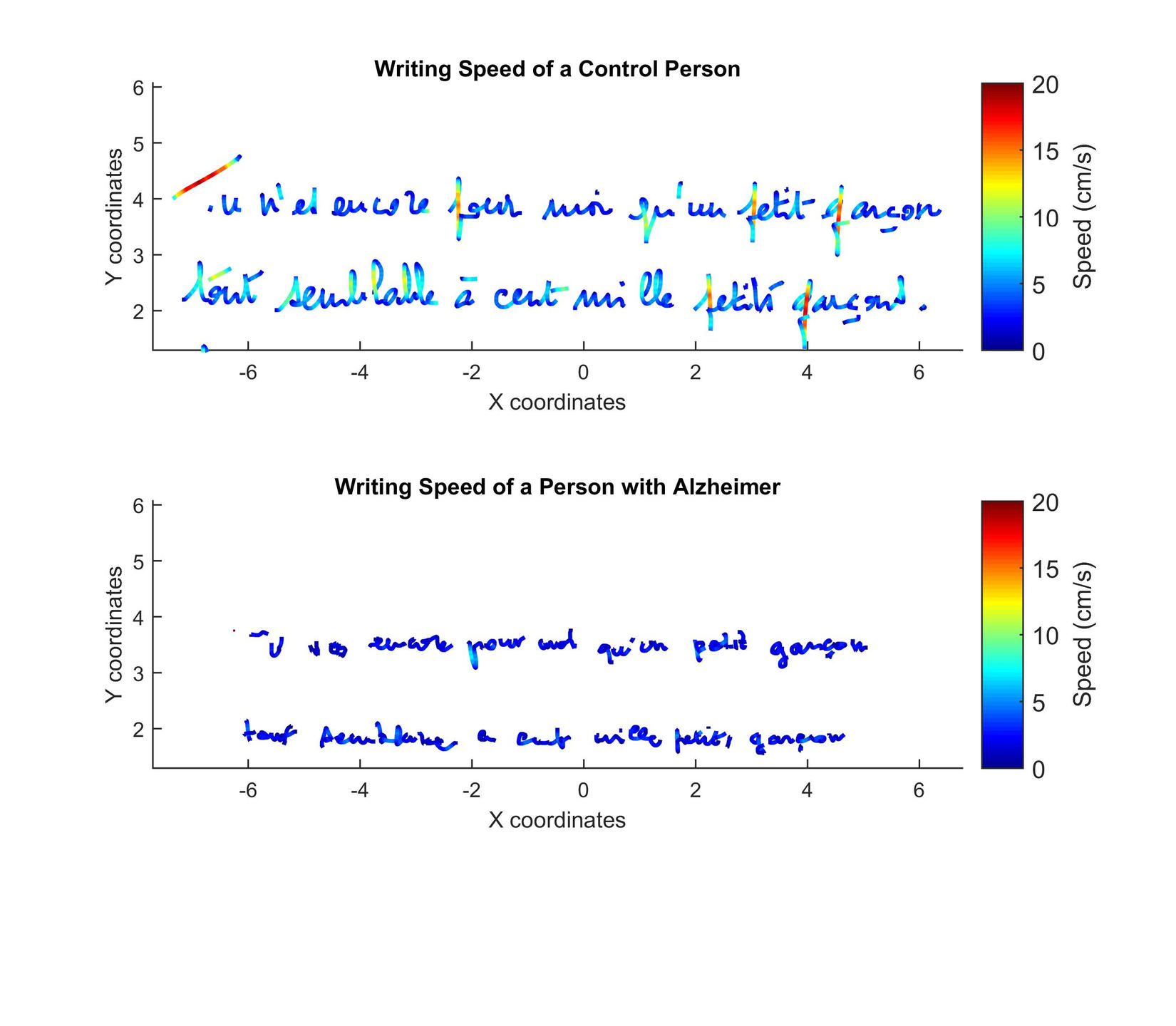

Meanwhile, in Evry (south of Paris), the ARMEDIA team is also on a quest for a dependable way to diagnose Alzheimer’s. To complement the diagnosis methods of imaging and neuropsychological tests, the team is investigating writing, a specifically human: “high-level activity that calls upon the executive functions of planning, anticipation and speed regulation," point out researchers Sonia Garcia-Salicetti and Mounîm A. El-Yacoubi. "A neurodegenerative disease will affect these faculties so there is an impact on writing.”

The ARMEDIA tool comes in the form of an electronic tablet on which a piece of paper can be placed, and written on with a pen. Based on what the team calls a “natural activity,” this technique has the key advantage of being both “easy-to-use and non-invasive.”

The tablet digitizes the trajectory of the pen on its surface, yielding a series of measurements, such as the position of the pen. Rather than recognizing the handwriting, the device analyzes “time-related signals from which kinematic information can be extracted” in order to detect any significant handwriting degradation, the scientists explain. In this way, the system can identify Alzheimer’s symptoms like undue jerkiness, slowness or stiffness. Not only are pen movements on the tablet recorded, but also those up to 1 cm from the surface—an important indication of a person’s hesitations.

The ARMEDIA team, in conjunction with the geriatric unit at the Paris-based Broca hospital, is collecting writing data from Alzheimer’s sufferers, non-sufferers, and people with mild cognitive impairment. In addition, the researchers have been studying the impact of age on writing in order to differentiate normal ageing from a pathological condition. Mathematical and statistical analysis techniques enable them to convert this data into models for a future diagnosis tool.

Caring for the future

Once a person has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, there is no getting around the fact that this disease is, for now, irreversible. Helping patients cope with it in their daily lives is therefore another pressing need—which CNRS scientists have also taken into account.

A dedicated project is also being developed by ARMEDIA’s Mounîm A. El-Yacoubi, in collaboration with Mossaab Hariz. Fitted with a camera to “watch” users, Juliette is a Nao humanoid robot, whose activity-monitoring function extends beyond Alzheimer’s sufferers to, for example, children with developmental difficulties. At present, the robot can identify 11 actions, including opening a door or walking, which it has “learned” by matching algorithmic parameters with a gesture viewed through its camera—and repeatedly performed by different persons to allow for variations. Deviations from the set parameters can thus be identified as abnormal, and alerts issued if necessary. As El-Yacoubi explains, the robot may be trained to detect whether a person forgets to take their medication at a given time—a known risk in the case of an Alzheimer’s sufferer. “The robot can also find out if the patient falls, enquire on their state and notify relatives in case of danger.” In relation to other activity-recognition systems, Juliette innovates in that it is fully integrated, requires no external computer or sensors. After developing a first prototype, the team is now seeking to boost the robot’s capacity “to solidly recognize a wide number of gestures and objects in quasi-real time, as well as adapt to its environment and user.”

Follow your every step

Assisting Alzheimer’s patients is also the goal of another SAMOVAR team, ACMES, whose systems provide aid in home and outdoor routines. Computer scientist Daqing Zhang indicates that when sufferers are outside in unfamiliar—or even familiar—environments, “disorientation and wandering are frequent symptoms of memory and cognitive impairment.” The team has therefore designed a technique to track patients and “reduce the burden on caregivers for whom full-time monitoring is laborious.” Their real-time device relies on GPS data to create models tracing a user’s regular itineraries, marked by frequent destinations, in graph form. An algorithm developed by the team can identify deviations from usual routes and send out alerts to help the user get back on track.

Indoors, ACMES has devised smart reminder methods to tackle forgetfulness in two ways. Firstly, “context-aware” sensors fitted in the home can recognize users' activity, assess situations, and react intelligently. If, for example, a patient has forgotten to turn off a stove after receiving a phone call, a reminder is issued in the form of a “voice message, visual cues or video clips on devices such as mobile phones or speakers, to ensure that the person understands what to do next.” A second method helps users with task scheduling: should sufferers miss a task—locking the front door for instance—the system will “reschedule it according to the urgency and execution time” of all other chores. Pending commercialization, the ACMES systems have been prototyped and testers trialed in homes in several EU countries.

Daqing Zhang sums up his aim as “offering low-cost and non-intrusive solutions.” An objective shared by his fellow CNRS scientists as, in different ways, they sharpen a range of 21st century tools to face Alzheimer’s growing prominence. While a cure is yet to be found, the development of new diagnosis and support methods will hopefully help society be better prepared for this ever-increasing reality.

- 1. Laboratoire lorrain de recherche en informatique et ses applications (LORIA - CNRS / Université de Lorraine).

- 2. Services répartis, Architectures, MOdélisation, Validation, Administration des Réseaux (SAMOVAR - CNRS / Institut Mines-Télécom / Télécom Sud Paris).

- 3. Algorithmes, Composants, Modèles Et Services pour l’informatique répartie.

- 4. Alzheimer’s Association, “Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and figures,” Alzheimer’s & Dementia (2015). 11(3): 332-384.

Explore more

Author

As well as contributing to the CNRSNews, Fui Lee Luk is a freelance translator for various publishing houses and websites. She has a PhD in French literature (Paris III / University of Sydney).