You are here

Global warming in France may be worse than thought

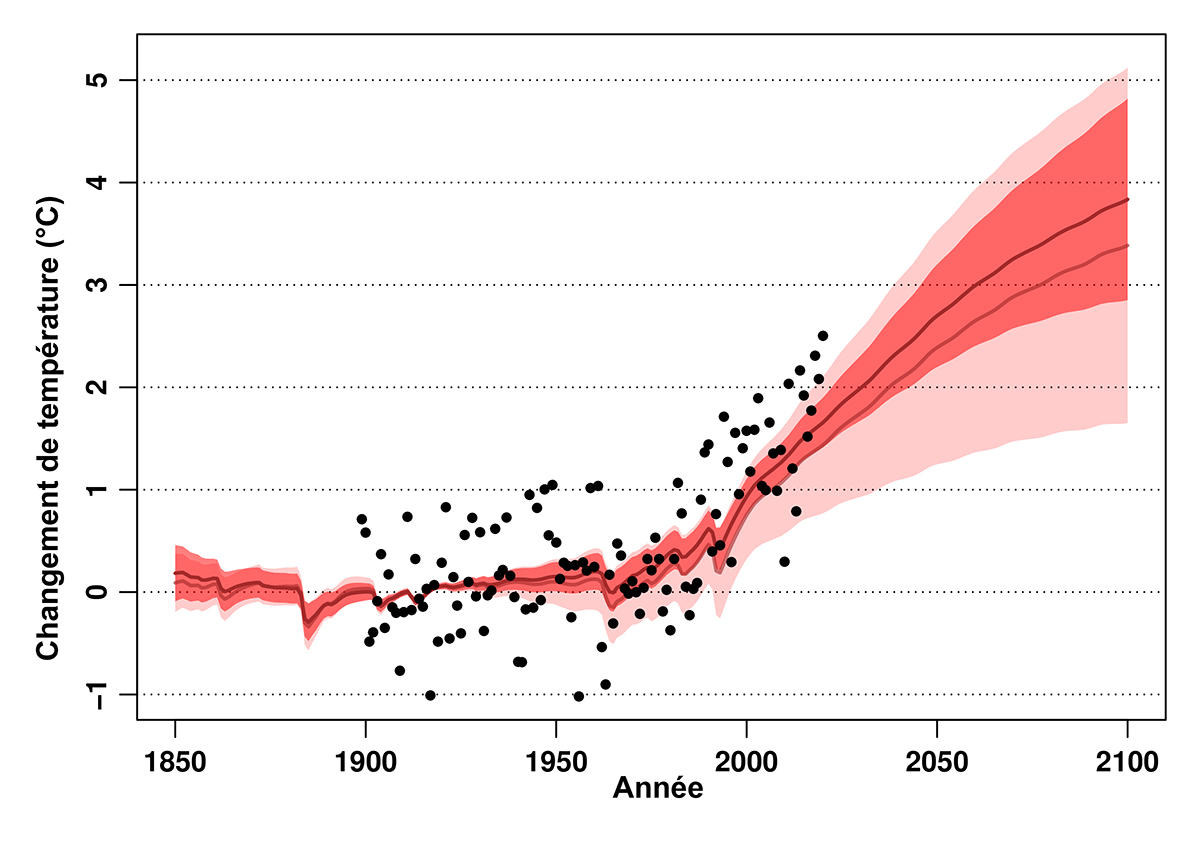

There is little room for climate optimism these days. In France, global warming during the 21st century could be 50% more severe than previously believed, according to new climate projections recently carried out by a research team from the CNRS, the French national meteorological service Météo-France, and the CERFACS centre for advanced research and training in scientific computing.1 If current trends in carbon emissions continue, the average temperature in France will be 3.8 °C higher than at the beginning of the 20th century, a figure that poses huge challenges in terms of adaptation and that could well lead to drastic changes in French agriculture and ecosystems.

To arrive at this result, the most robust available to date, the researchers relied on a novel methodology. Developed by the same team, this approach was used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in the first part of its sixth report, published in 2021. The main innovation is that models are constrained based on observed climate data. In other words, the researchers took a range of climate simulations carried out with IPCC models to identify those that were consistent with temperature data collected for more than a century. This enabled them to determine the most reliable future climate projections and reduce uncertainties.

The other original aspect of this work, which was published on 4 October in the journal Earth Systems Dynamics, is that it provides projections at a national level. “The IPCC produces climate change scenarios both on a global scale and on that of large regions such as Europe or the Mediterranean basin. But not below. And yet there is an urgent need for narrower projections,” explains Aurélien Ribes, a researcher at the French National Centre for Meteorological Research (CNRM).2 Major policy decisions are mainly taken nationally. It was therefore vital to use this new methodology to obtain climate change scenarios for France. To do so, the researchers used data collected by some thirty weather stations from around the country, known to have provided consistent temperature records over long periods of time. In fact, the first reliable information available to researchers dates back to 1899.

The team used this evidence to calculate the current rate of global warming. They showed that the mean temperature in present-day France is 1.7 °C higher than it was between 1900 and 1930. This figure is well above the worldwide average increase, which the IPCC estimates to be 1.2 °C. However, for the researchers, there is nothing unusual about this. “The global temperature surge takes into account the oceans, which are warming more slowly than the continents,” Ribes explains. On land, it is 1.6 °C, so France is no exception.

Unsurprisingly, climate models show that future increases are directly proportional to greenhouse gas emissions. Whatever deniers may claim, there can be no doubt about the human origin of climate change in France, as elsewhere. One thing however did surprise the researchers: the impact of aerosols. “We never imagined that they had such an influence on the French climate,” says Julien Boé, from the Climate, Environment, Coupling, Uncertainties unit (CECI).3 “We found that, until the 1980s, the effect of aerosols masked global warming to such an extent that instruments hardly detected it.”

Aerosols are suspensions of fine particles in the atmosphere. Large quantities of them are released as a result of pollution produced by human activities, and especially by the burning of fossil fuels. This pollution has a powerful cooling effect, since the particles prevent incoming solar radiation from reaching the Earth's surface. Until the 1980s, pollution and greenhouse gas emissions increased in parallel, and their impacts on the climate cancelled each other out. But then, towards the end of the 20th century, new regulations and cleaner technologies dramatically reduced pollution. As a result, the effect of aerosols rapidly declined, while the temperature curve rocketed at a rate that surprised the scientific community.

Unbearable summers by 2100

As a next step, the researchers turned to the future and attempted to predict the climate in France at the end of the 21st century. To do this, they used climate simulations based on the various IPCC scenarios describing the state of the world in 2100. These scenarios range from the most optimistic, in which a massive international effort has made it possible to achieve carbon neutrality as early as 2050, to the most pessimistic, with huge inequalities, and continuing reliance on gas, oil and coal. Between these two unlikely extremes, experts believe an intermediate situation in which carbon emissions neither increase nor decrease drastically best matches current trends and the climate commitments made by the major emitting nations for the next few years.

On the latter basis, the researchers show that in 2100 France could be 3.8 °C warmer than in the early 20th century, a frighteningly high increase. A temperature rise of this magnitude would be felt particularly acutely in summers, which could be some 5 °C hotter on average than in the decades between 1900 and 1930. “This will have very severe consequences on ecosystems and crops. Heatwaves will become harsher and more frequent, while droughts will be more drastic and long-lasting. In these conditions, one of the key points will be to find ways of preserving and using water resources,” Boé says. With a mean temperature rise of 3.8 °C, entire ecosystems could disappear, and the agricultural landscape be radically transformed.

These projections are a real wake-up call that should be used to implement mitigation and adaptation policies. CNRM researchers now intend to move down to even smaller scales and simulate future climate conditions in the various regions of France. In addition, they're hoping that other teams around the world will adopt their methodology. “The code on which this work is based is now available to everyone. This should make it easy for other teams and meteorological services to carry out these calculations for their own country or region,” Ribes explains.