You are here

The call of the forest

(This article is taken from the dossier "La forêt, un trésor à protéger" ("The forest, a treasure to be protected"), originally published (in French) in issue 16 of the journal Carnets de science).

Could our forests disappear? The 2023 megafires were so violent, and so premature, that they threw into sharp relief the vulnerability of the world's woodlands. The province of Alberta in western Canada was engulfed in flames in early spring. 3,500 square kilometres (km2) went up in smoke in under a week, and 30,000 people had to be evacuated. Meanwhile in Russia, 6,000 km2 of boreal forests burnt down in the Urals and Siberia in May. Spain, Greece and the entire Mediterranean basin were also affected, while fires raged in the southwestern French département of Pyrénées-Orientales as early as April, setting a new record.

"You have to be very cautious when it comes to analysing wildfires," underlines Laurent Simon, emeritus professor of geography at the Université Panthéon-Sorbonne and a member of the Social Dynamics and Recomposition of Spaces laboratory (LADYSS)1. "Worldwide, the area affected by forest fires hasn't increased much over the last thirty years, with 3 to 4 million square kilometres burnt down annually according to satellite data from the Copernicus programme. On the other hand, the nature of the blazes has completely changed. There used to be lots of small ones. But we are now faced with very large ones that are absolutely devastating."

These megafires, which first appeared around fifteen years ago, are caused by global warming and the droughts hitting forested regions. But those aren't the only factors. "For example, in California and Australia, they often start at the interface between urban areas and woodland, because the closer housing gets to forests, the greater the risk of fire. In Russia, the drought of 2023 was compounded by the fact that half the forest rangers had been dismissed. The blazes had plenty of time to spread before being spotted," Simon points out.

Exactly what is a forest?

In any case, the fires have taught us one thing: forests are complex objects that defy simple description. In fact, just defining them is quite a challenge. Exactly what is a forest? Can savannah with very patchy tree cover or the so-called “urban microforest” at the end of my street really be called forests? "Today, the definition proposed by the FAO, the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, is the most widely employed internationally," Simon explains. "It stipulates that a forest is where tree cover extends over at least 10% of the surface, with a minimum area of half a hectare, and adult trees are at least 5 metres high."

This is a fairly broad characterisation resulting from an international compromise, and it was used particularly in negotiations about carbon credits and the contribution of each country to the reduction of greenhouse gases (forests are a highly effective natural carbon sink). However, not all scientists are happy with it, starting with ecologists, who argue that a forest is not solely made up of its tree cover, but also of its complex ecosystem. "A clump of trees covering half a hectare has far less biodiversity than a huge forest, and doesn't constitute a fully functional ecosystem," says Philippe Grandcolas, deputy scientific director of CNRS Ecology & Environment.

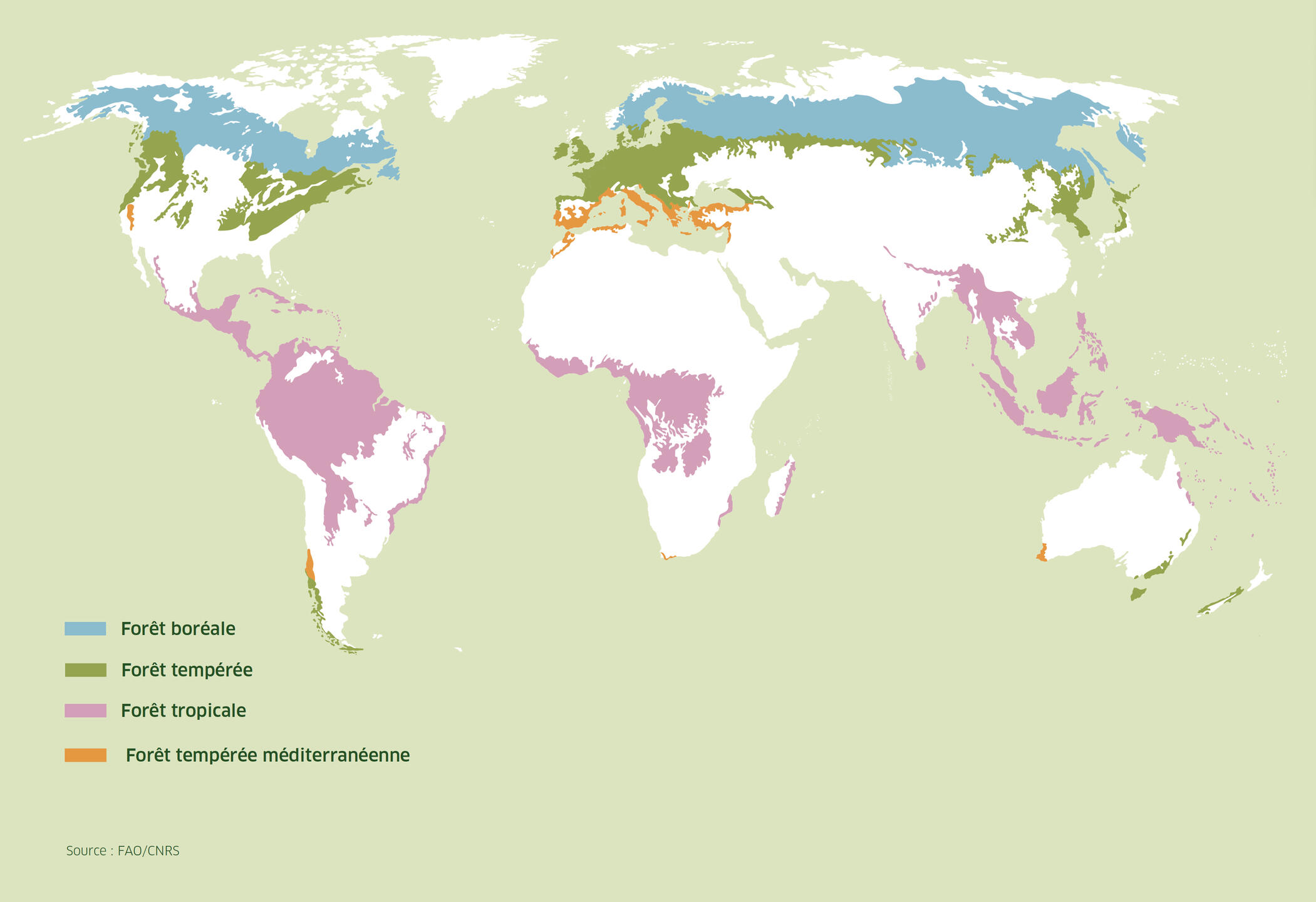

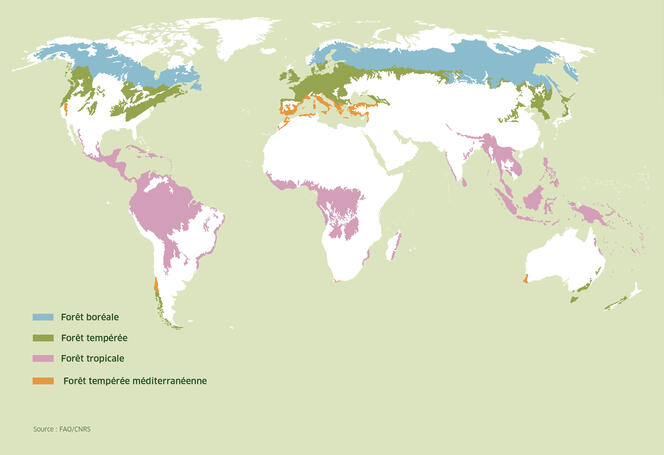

Such quibbling aside, forests as defined by the FAO currently cover 30% of the Earth's land surface, some 44 million square kilometres. They can be divided into four main types. In the far north, boreal forests, vast expanses of conifers found from Russia to Canada and Scandinavia, represent slightly over a third of the world's forest area. Tropical forests with their hundreds of deciduous and evergreen species, located on either side of the equator, account for just under a third of the total, but make up by far the largest forest biomass and are the most complex ecologically. Then come the temperate woodlands, principally in Europe and the US, which contain a mixture of deciduous trees and conifers. And finally there are the Mediterranean-type forests with their sclerophyllous (hard-leaved) vegetation, found not only around the Mediterranean, but also in southern California, South Africa's Cape region, and around Valparaíso in Chile.

These four types of forest differ not only in their general appearance, but also in the way they function. "Boreal and temperate forests are both controlled by the cold: in winter (which is much longer for the former), the trees rest and stop photosynthesising. The opposite is true in Mediterranean forests, which are dependent on heat and, above all, on water stress: at the height of summer droughts, trees stop breathing so as not to lose their water, and very noticeably reduce their vegetative activity," Simon explains. Tropical rainforests, on the other hand, are active all year round, with no marked seasonal rhythm, and are always green.

Pointing the finger at mass logging

Whereas natural woodland forms complex ecosystems, many forests are frequently subject to extreme simplification, and are often reduced to mere "fields of trees", rows of individuals of the same species and age. This is due to certain types of forestry practice that prioritise straightforward management, using fast-growing conifers (which burn more easily) that are all planted, and therefore all harvested, at the same time. This method, known as clearcutting, consists in felling all the trees over a very large area, leaving the ground completely bare.

However, "with global warming, these standardised forests form impoverished ecosystems that lack resilience", says Guillaume Decocq, a botanist at the EDYSAN laboratory2. "They have little resistance to droughts, storms and fires, and are also more vulnerable to attacks by pathogens and pests." Simplified to the extreme, constantly impacted by megafires and storms, fragmented by deforestation and by the roads, motorways, and railways that cross them, our forests are in trouble. Yet they are essential because of the host of services they provide.

The second-largest natural carbon sink after the oceans, forests contribute to the global climate balance, and are home to 80% of Earth's biodiversity. They produce timber for construction, heating and cooking for millions of humans, and could soon be a source of biofuels for the aircraft of the future. And with half the world's population now living in cities, they have become highly popular recreational areas.

Conflicting expectations

"People today have considerable and frequently conflicting expectations with regard to forests," Simon points out. "We want them to host a rich and flourishing biodiversity, where nature is protected, and yet at the same time we expect them to provide us with more and more biobased materials for the energy transition. And we also want to be able to go hiking or mountain biking there." Unsurprisingly, conflicts of use are on the rise. "In France, where two thirds of forests are privately owned, disputes between forest owners, loggers and the general public are ever more frequent, especially over clearcutting, which people find increasingly unacceptable," Decocq adds.

So, who really owns the forests? This is a key question according to the botanist, who points to the latest developments in French legislation on the subject. "From now on, anyone who enters a private woodland, even an unfenced one, is liable to a fine. In early 2024, in the Vosges (northeastern France), the new owner of a forest crossed by several hiking trails announced that he was banning all access to it."

Do forests form part of the global heritage of humanity, and indeed of all living things? How can all our different needs be balanced? "New forestry practices that are more compatible with the forest ecosystem are beginning to emerge," says Simon, who remains convinced that forests can co-exist with humans. "Forests have been impacted by humans for thousands of years," the geographer points out. “In the Middle Ages, Europe's woodland was anything but a wilderness. Even today's Amazon rainforest, often mistakenly thought to be a pristine wilderness, is the result of thousands of years of human activity." ♦