You are here

WWI: Origins of a Conflict

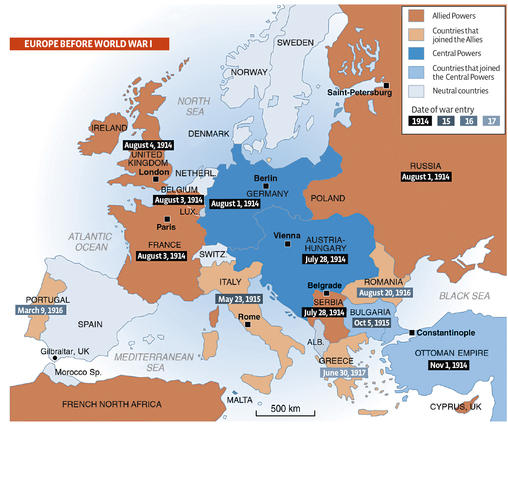

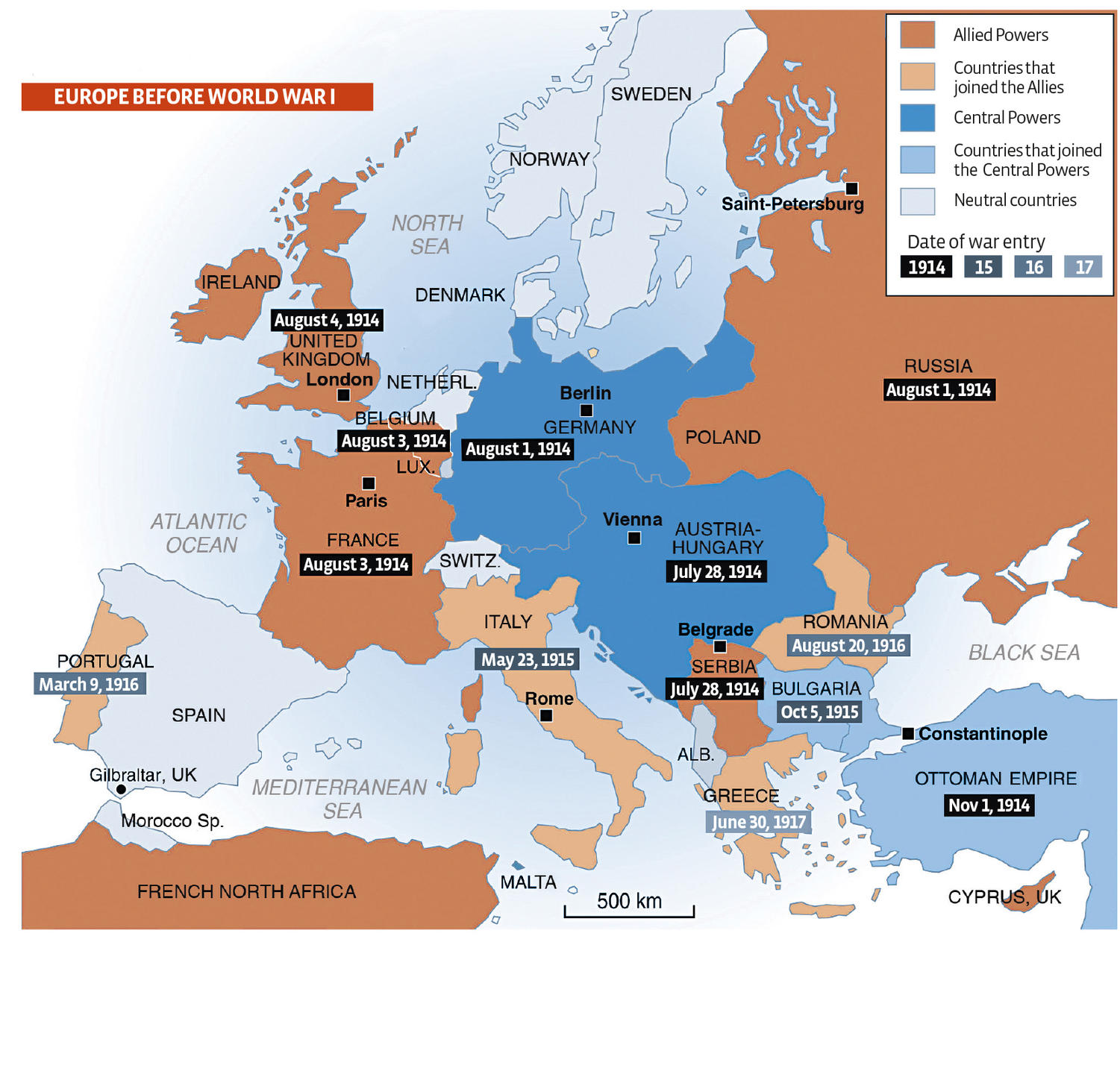

Treaty of Versailles, June 28, 1919. Article 231: “ Germany accepts the responsibility for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected ” By placing the entire responsibility for starting the Great War on a single nation, the famous treaty, signed in the Hall of Mirrors at the Palace of Versailles, puts forth a historic interpretation of the conflict. Yet many others are possible.

“The question of responsibility for the war has been the subject of an impassioned debate over the past century,” explains Nicolas Beaupré, researcher and professor at the University of Clermont-Ferrand. This issue is extremely sensitive, highly political, and fraught with consequences: indeed, the humiliation inflicted upon the Germans in 1919 provided a fertile ground for the rise of Nazism, and contributed to the outbreak of World War II.

The hunt for clues

Since the 1920s, the so-called “War Guilt Clause” has been called into question. “The parties involved have been waging a war of documentation to sway public opinion, each side publishing collections of diplomatic exchanges to downplay its responsibility while emphasizing that of the opponent,” explains Nicolas Offenstadt, a researcher at the LAMOP.1

Based on these sources, whose interpretation was never clear-cut, historians more or less agreed that all belligerents shared responsibility for the hostilities in 1914—until a German historian dropped a figurative bombshell. In 1961, Fritz Fischer published Griff nach der Weltmacht2 ("Germany’s Aims in the First World War"), an iconoclastic book met with harsh criticism from his peers. After consulting new archives, the author concluded that Germany did indeed bear most of the responsibility. “According to Fischer, Germany decided to risk war to further expand its territorial and economic power in Europe,” explains Offenstadt. “The historian then draws a parallel between Wilhelm II’s ‘Weltpolitik’ (a foreign policy championed by the Kaiser and aimed at developing a colonial empire proportional to Germany’s economic power and Hitler’s Pan-Germanism (which aims to unite all of Europe’s German speakers in one ‘Greater Germany’).”

The theory of shared responsibilities

In France, interest in the origins of the Great War gradually faded “as the research focus shifted from diplomatic history to the social and cultural evolutions of the period,” says Beaupré. But in the UK and the US, it remained a significant issue, as testified by the 25,000 books and articles published by the end of the 20th century. Today, interest continues unabated: in 2012 and 2013, three major essays were published on the mechanisms that led to World War I3 — all shifting the blame to the Entente countries: Russia and Serbia, but also France.

Published in March 2013, The Sleepwalkers, by Australian historian Christopher Clark, is possibly the most widely hailed of the three. “Clark is a polyglot who can read German, Russian, and also the Balkan languages. This enabled him to consult a number of previously-unexamined sources,” Beaupré points out. Clark’s exhaustive study rehabilitates the theory of shared responsibility: “The outbreak of war in 1914 is not an Agatha Christie drama at the end of which we will discover the culprit standing over a corpse in the conservatory with a smoking pistol,” he writes. “There is no smoking gun in this story; or, rather, there is one in the hands of every major character. Viewed in this light, the outbreak of war was a tragedy, not a crime.” In other words, there is not just one, but many responsible parties, the first of which is Serbia, Clark believes.

An assassination

On June 28, 1914, while on a visit to Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia-Herzegovina recently annexed by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the throne, is assassinated by the young terrorist Gavrilo Princip. Far from trivializing it as a relatively minor incident that served as a pretext for Austria-Hungary and Germany to declare war, Clark sees the assassination as the culmination of decades of aggression by a country obsessed with the unification of “Greater Serbia” and heavily infiltrated by terrorists. In the run-up to World War I, Serbia had doubled its territory following the two Balkan Wars (1912-1913) and its president, Nikola Pašić, had no control over the most influential extremist group, the “Black Hand,” whose Pan-Serb views he adhered to.

Chain Reaction

At the head of both the Serbian secret service and the Black Hand, Lieutenant Colonel Dragutin Dimitrijević, also known as “Apis,” instigated the attack of June 28 because the Serbs saw the annexation of Bosnia-Herzegovina as an affront: the country’s population included orthodox Serbs and therefore belonged to the future Greater Serbia. Franz Ferdinand’s announced intention to grant Bosnia relative autonomy further fuelled the Serbs’ anger: Bosnians would never embrace the cause of Greater Serbia if they were to become self-governing members of a prosperous empire.

In Clark’s view, everything suggests that Pašić was aware of the assassination plot but only gave Austria a cryptic warning—enough to protect his own position while ensuring that his message would not be taken seriously. The historian believes Pašić may have been driven by his belief “that the final historical phase of Serbian expansion would in all probability not be achieved without war. Only a major European conflict in which the great powers were engaged would suffice to dislodge the formidable obstacles that stood in the way of Serbian ‘reunification.’”

Of course, Belgrade was not the only warmonger. Russia, weakened since its defeat by Japan in 1908 and concerned about the rising power of its German neighbor, had good reason to enter another conflict, in a bid to “reshuffle the deck.” Indeed, Russia seemed to rush into war: it was the first country to call for a general mobilization, just 10 days after the Archduke’s assassination. By encouraging Serbia to stand up to Austria-Hungary—which had given the Serbs an ultimatum following the attack—Russia was guilty of “escalating a local quarrel and accelerating the war,” writes Sean McMeekin in July 1914: Countdown to War.

Meanwhile, how did France—then an ally and creditor of both Russia and Serbia—react? When the crisis broke out, French President Raymond Poincaré was in Saint Petersburg, on a state visit to Russia. “Recent studies show that he did not try to dampen the Czar’s appetite for war,” Beaupré notes. “According to historian Stefan Schmidt, he even encouraged Russia to enter the fray, falsifying diplomatic documents in order to portray Germany as the aggressor. But this interpretation must be tempered: more than pushing Russia into war, France was mainly trying to remain on good terms with its allies.”

Nonetheless, Germany certainly has a fair share of responsibility. Bolstered by his country’s skyrocketing economic development, Wilhelm II dreamed of expansion. A dream until then thwarted by Britain and France, long-time rivals that were now at peace following the Entente Cordiale of 1904 and were planning to resolve on their own the conflicts arising from the breakup of the Ottoman Empire. Yet a war could change everything.

Was such a horrendous conflict really fought to control a few scraps of land? “There is a crucial element to bear in mind,” emphasizes Offenstadt. “The protagonists expected it to be over quickly. Very few imagined that it could reach that scale, causing such unprecedented violence.”

In short, none of the countries involved really wanted war. They were, in Clark’s words, “sleepwalkers, watchful but unseeing, haunted by dreams, yet blind to the reality of the horror they were about to bring into the world.”

More on the same topic:

Legacy of World War I

Laboratories at War

- 1. Laboratoire de médievistique occidentale de Paris (CNRS / Université de Paris-I).

- 2. Fritz Fischer, Germany’s Aims in the First World War (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1967).

- 3. Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914 (London: Penguin, 2013); Sean McMeekin, July 1914: Countdown to War (New York: Basic Books, 2013); Margaret McMillan, The War that Ended Peace: The Road to 1914 (New York: Random House, 2013).

Explore more

Author

To read / To see

The sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914.

Christopher Clark

(London: Penguin, 2013)

The War that Ended Peace: The Road to 1914.

Margaret McMillan

(New York: Random House, 2013)

July 1914: Countdown to War.

Sean McMeekin

(New York: Basic Books, 2013)