You are here

World War I: Asians on the European Front

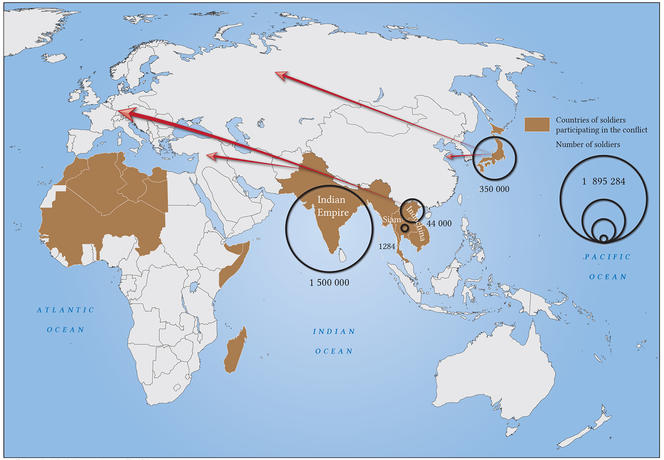

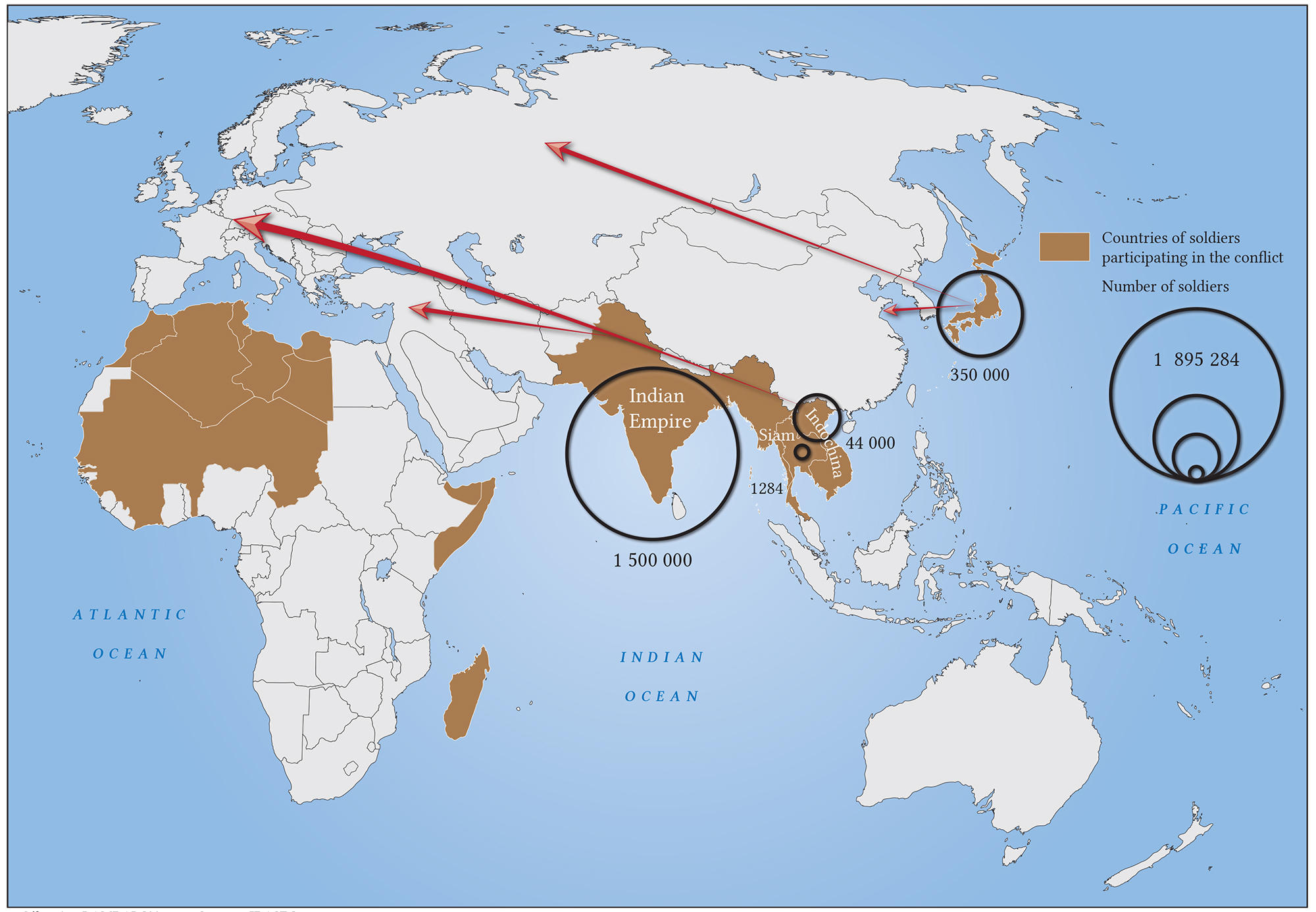

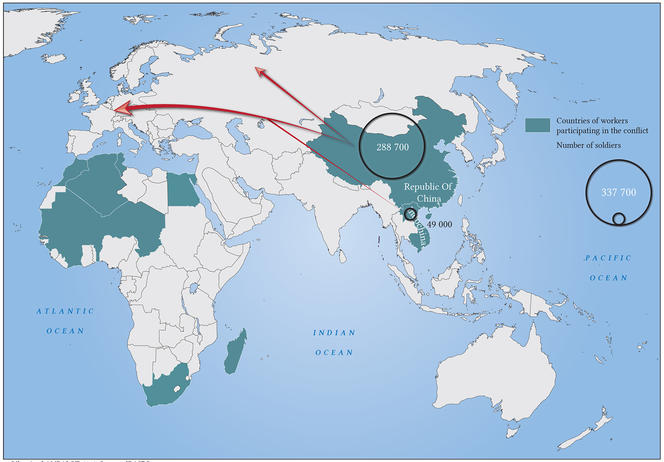

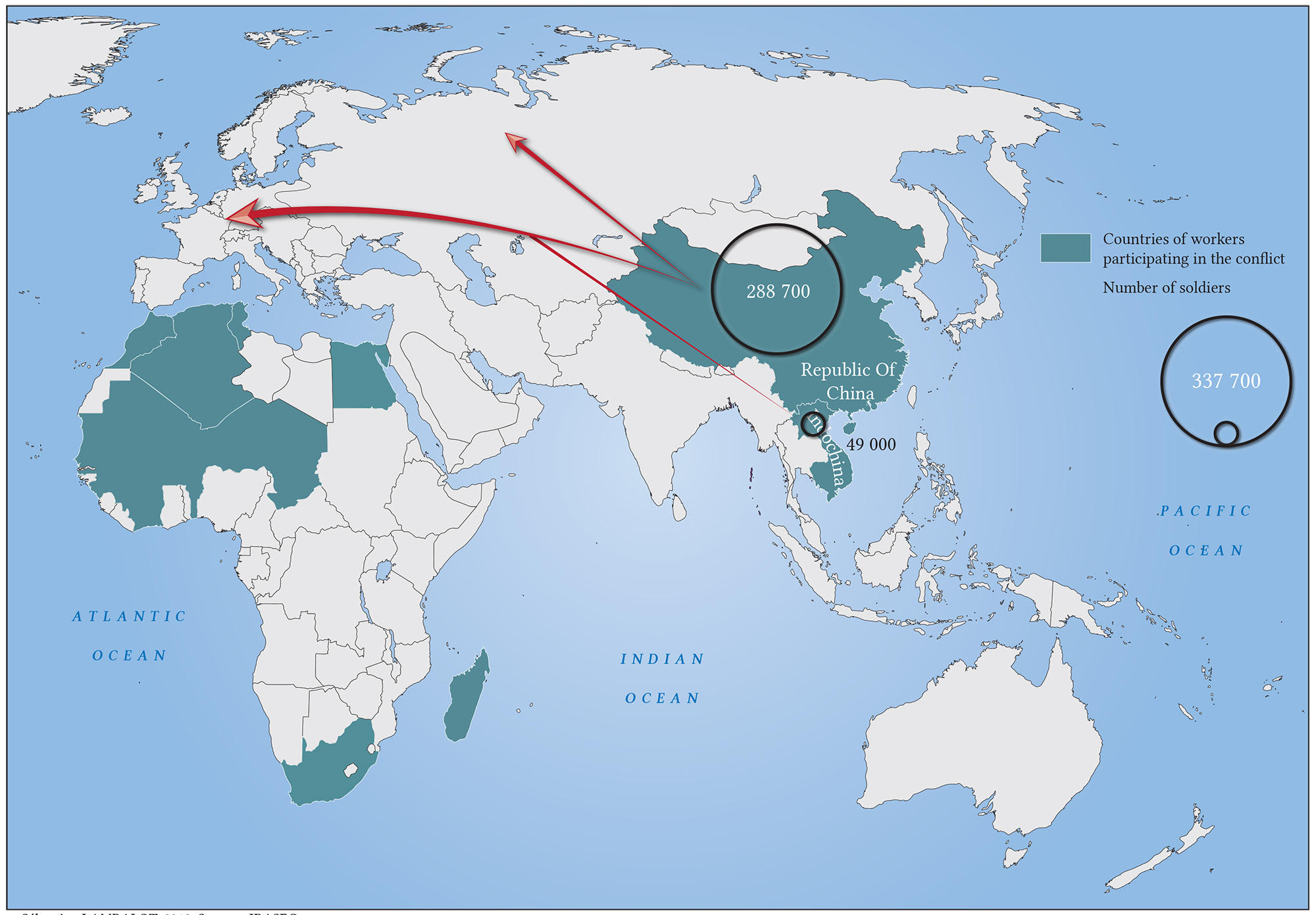

While the commemorations of the First World War offer an occasion to remember the hardships endured by the “Poilus” (French infantrymen) in the trenches, little is known about the vicissitudes suffered by nearly 2.5 million fighters and workers from Africa and Asia, 71% of whom were from Asia—mostly India, China and Vietnam. Who indeed were the 1,723,000 Asians who came to the battlefields of Europe and the Middle East between 1914 and 1919, to be plunged into the inferno of all-out war?

At a time when the governments and societies of Asia were facing an onslaught of Western imperialism and the imposition of “unequal treaties”, World War I shifted large Asian populations in the opposite direction for more than five years.

Unprecedented mobility between Asia and Europe

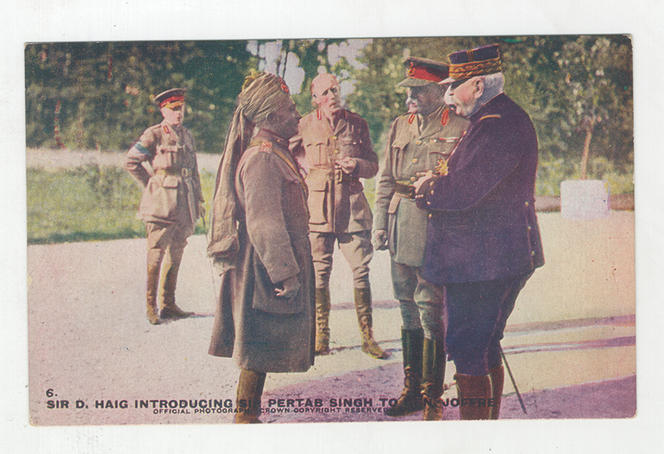

Colonial propaganda promised good wages to Asians who joined the colonial forces, an offer that drew many farmers from the poor regions of Punjab, Vietnam’s Red River Delta and the French concession of Guangzhouwan, who lived in fear of famine. But certain members of the Indian elite also heeded the call, like the aristocrat Rajput Amar Singh and Sir Pertab Singh, Regent of Jodhpur and a friend of Queen Victoria. The same was true in Vietnam, where the well-educated nationalist and reformist Phan Chu Trinh (1872-1926) called on his countrymen to support France’s war effort, in the hope of benefiting, in return, from a policy of assimilation that would help forge a modern elite in his country, and political representation worthy of what one would expect of French democracy.

But what are the sources for writing a history from their point of view, for describing their first encounter with Europe and Europeans in an unfamiliar cultural environment and a difficult context, whether in the trenches or the munitions factories? Beyond the locals’ curiosity for these newly-arrived “exotic” populations, letters seized by military censors, diaries and written and visual archives offer insights into the experience of these Asians in Europe. These sources make it possible to trace the individual stories of soldiers, workers, diplomats and students, revealing their discoveries and amazements, hopes and disappointments, day by day.

Newfound mobility and opportunities

Beyond the Eurocentric vision of them as mere subordinate auxiliary forces serving the colonial powers, these workers and soldiers were also men of action, who took an exceptional opportunity to travel very long distances. In the colonies, any movement, especially to the ruling countries, was closely regulated. Under these circumstances, transcontinental mobility could change their individual—and perhaps even collective—destiny. Discovering the everyday life of the societies that colonised them, witnessing their political and social movements, and seeing the colonial powers weakened by warfare among themselves had an impact on these men once they returned to their homeland.

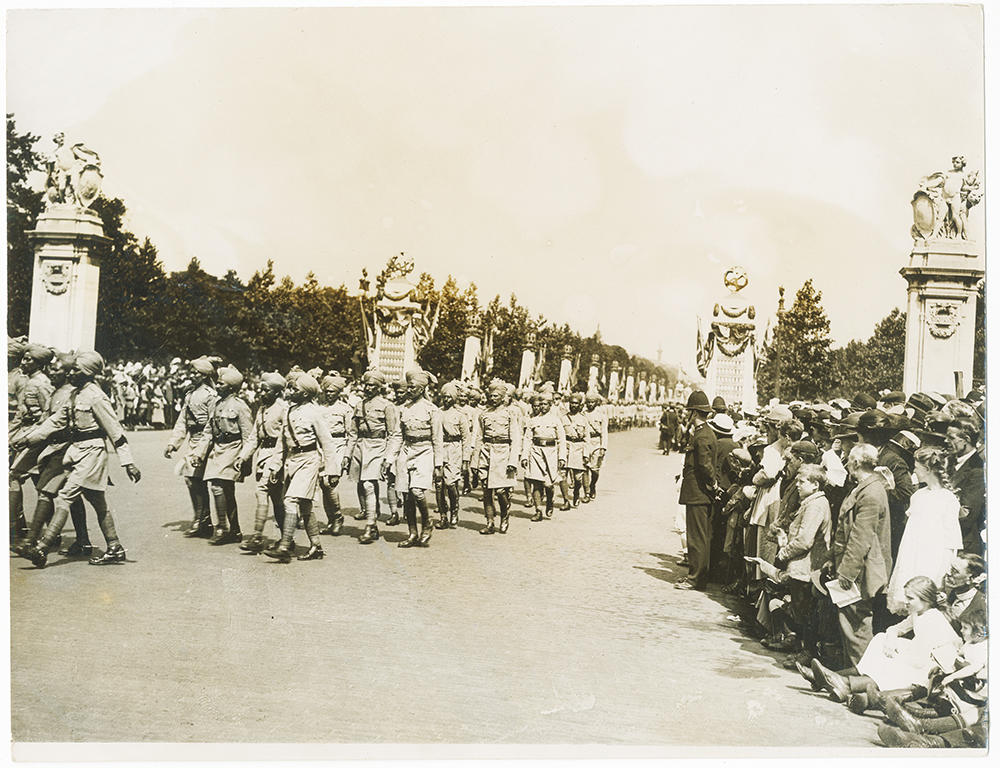

After an arduous journey, often under abject sanitary conditions and without adequate clothing for the European climate, the Asian troops landing in European ports discovered a totally new cultural and social reality, including people of all socioeconomic backgrounds, many of whom much different from the colonial masters they had known. The arrival of Indian troops in Marseille (southeastern France) in 1914 sparked the curiosity of the locals, who were impressed by the appearance of the Sikhs, who in turn were amazed by everything they saw of the French cities and their inhabitants. They also aroused suspicion among French workers, who already saw Vietnamese and Chinese labourers, requisitioned because of their military status, as competitors or strikebreakers.

Sepoys on the Western Front

The India Gate, a war memorial on Rajpath Boulevard in central New Delhi, stands as a reminder of the sacrifice made by the 74,000 soldiers who died in the war, out of a total of 1.3 to 1.5 million Indian fighters and workers: “To the dead of the Indian Armies who fell and are honoured in France and Flanders, Mesopotamia and Persia, East Africa, Gallipoli and elsewhere in the Near and the Far-East…” It was Indian troops who halted the German advance in Ypres (Belgium) in the autumn of 1914. Hundreds of sepoys (Indian soldiers) fell in Neuve Chapelle (northern France), and more than a thousand, including many Muslims, in Gallipoli in the Dardanelles between February 1915 and January 1916, fighting against Germany’s Ottoman ally.

Although relatively few of the Asian soldiers were literate, many left behind personal accounts. According to the Bengali writer Amitav Ghosh, Sisir Sarbadhikari’s book Abhi Le Baghdad (On to Baghdad) (1958) is one of the most remarkable wartime memoirs of the 20th century. Based on his own diary, which he hid in his boots, the book describes the tribulations of the British Indian forces in Mesopotamia, Syria, Turkey and the Levant. Another book, At ‘Home and the World’ in Iraq 1915-17 Kalyan Pradeep, by the Bengali author Mokkhoda Debi, published in 1928, recounts the life of her grandson Kalyan Mukherji. After studying medicine in Calcutta and in Liverpool, he enlisted as a doctor in the Medical Service of the British Indian Army and joined the Expeditionary Corps in Mesopotamia in March 1915. He died two years later at the age of 34, interned as a prisoner of war in a Turkish camp in Ras El Ain. The book reproduces the letters that he sent to his family, many describing the disastrous Mesopotamian campaign (1915-16).

The memoirs of Sainghinga are another example. A veteran of the Labour Corps from the Lushai Hills of northeastern India (now Mizo Hills, part of the state of Mizoram), he was one of the first to master Roman character writing in Mizo, a Tibeto-Burmese language spoken by fewer than 700,000 people today. Recruited as an interpreter, he recounts his war experience in Indopui (The Great War), published shortly before World War II.

Chinese workers: the exploitation of the coolies

Chinese workers formed the second largest group of Asians who arrived in Europe en masse to alleviate the Allies’ labour shortage, and because the Chinese authorities were hoping to protect their country against Japanese imperialist ambitions by aligning themselves with the Allied Forces. The French and British both drew upon their concessions in China and brought 140,000 recruits to France, divided into two groups: the Chinese Labour Corps, under British authority, was assigned to logistical projects in northern France, while some 37,000 Chinese arrived in Marseille in mid-August 1916, to serve as military workers under the auspices of the Colonial Labour Organisation Service (SOTC). Most were unskilled peasants from the province of Shandong, many of them illiterate. They were mainly used for maintaining factory equipment and repairing communication routes.

Forced to cope with wartime shortages and employers who had no qualms about ignoring agreements on equal pay, they were packed into special camps, housed in tents and crude barracks even in the middle of winter, with inadequate clothing and shoes. They lived in isolation among themselves, any contact with the locals being theoretically forbidden. Working conditions were harsh and the late payment of salaries was a frequent complaint, leading to strikes and riots in Boulogne (near Paris), for example. They also faced hostility from local workers, who saw them as unfair competition. In some northern French regions, including the Somme, the Marne and the Oise, they were suspected of assault, murder and thefts. After the armistice, many Chinese were deployed to the battlefields to recover the corpses, clear artillery shells and refill the trenches. About 2,000 stayed in France. Of those who returned to China, some became labour movement leaders in the 1920s, at a time when young students like Deng Xiaoping and Zhou Enlai were coming to France as student workers. Even less well-known are the 160,000 Chinese recruited by Russia between 1915 and 1917, who mined coal in the Urals, built railways in the polar regions, or worked as lumberjacks in Siberia or dockers in the ports of the Baltic Sea.

The Vietnamese: from Verdun to the assembly line

Of the 93,000 Indochinese soldiers and workers who came to Europe, most were from the poorest parts of the Tongkin and Annam regions, which had been badly hit by famine and cholera, and—to a lesser degree—from Cambodia (1,150). Some 44,000 Vietnamese soldiers served in combat battalions on the front in Verdun, in the Vosges (both in northeastern France) and on the Eastern Front in the Balkans. In logistics battalions they were used as drivers transporting troops to the front, stretcher-bearers or road crews. They were also in charge of “sanitising” the battlefields, mostly at the end of the war, working in mid-winter without warm clothing to allow French soldiers to return home sooner.

In addition, 49,000 Vietnamese were hired as workers under military authority between 1916 and 1919. Despite many women having taken over, there was still a labour shortage in the munitions factories, and these Vietnamese farmers were assigned to production sites in southern and southwestern France, like the Arsenal of Tarbes and the Bergerac gunpowder works. They were housed in makeshift camps overseen by gendarmes, forced to work at a furious pace on the assembly lines, at night, handling hazardous materials like explosives and gas… While the French government chose not to industrialise Indochina in order to avoid competing with companies in France, World War I contributed to the emergence of a Vietnamese proletariat of skilled workers. While serving in French factories, they discovered labour unions, city life and, last but not least, the experience of socialising with French women, which would have been unthinkable in Indochina.

The more egalitarian social relations they found in France contrasted sharply with the racial hierarchy imposed in the colonies. The postal censorship that was soon implemented placed the colonial contingents under the closest scrutiny. Letters and photos sent to their families provide a glimpse of their everyday life. Their return home after the war was not easy, as the sacrifices they had made were repaid with nothing but promises. Some of the Vietnamese who came to France during World War I—like Nguyen Ai Quôc, the future Hô Chi Minh—converted to communism, the only party that supported the right to self-determination. Some became active in political journalism while others joined the Vietnamese nationalist parties, demanding self-rule.

The Siamese engagement is still commemorated…

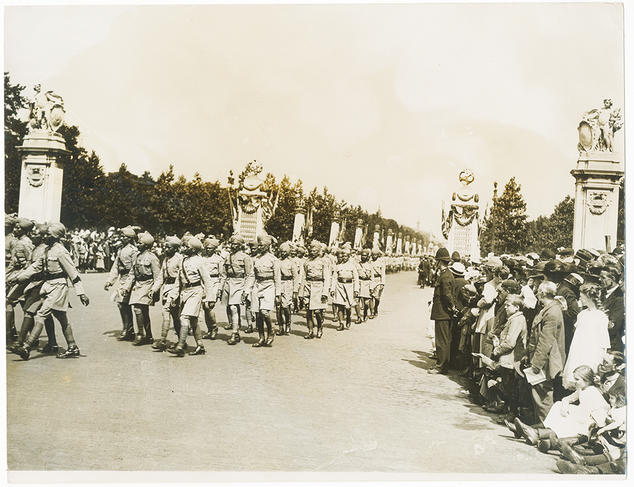

On September 22, 1917, Siam entered the war on the Allied side upon the initiative of King Vajiravudh (Rama VI, 1880-1925), who was educated in Britain for nine years. After the United States joined the conflict earlier that year, the king saw an opportunity to revise the unequal treaties signed with the Western powers in the 19th century, and show the world that the Siamese were “free and civilised”. A 1,284-strong force of volunteers, aviators, drivers and doctors enlisted, but did not reach Marseille until late July 1918. Although they were sent to flight and driving school, only one small Siamese automobile corps was deployed to the front, in September 1918, not far from Verdun. After the armistice, the Siamese contingent was put in charge of occupying the city of Neustadt in the Palatinate, and later participated in victory parades in Paris, Brussels and London. The last Siamese soldiers returned home in late 1919, and a celebration in their honour was held in Bangkok. A war memorial in the form of a pagoda still stands in Sanam Luang in the city-centre of Bangkok, not far from the old royal palace. It is the scene of a yearly Armistice Day commemoration, attended by the descendants of those volunteers, as well as representatives of the king and the Allied countries.

What impact did the war experience have on the lives of the Siamese volunteers after their return? It is difficult to generalise, but some of them joined forces to demand a change from absolute monarchy to a parliamentary system. Tua Lapanugrom and Jaroon Singhaseni, two of the seven founders of the Khana Ratsadon party, created in Paris in the 1920s, who succeeded in overthrowing the absolute power of the king in 1932, were former World War I volunteers. Several veterans played an active role in forging Siam’s new government and electoral policy between the two wars and during World War II. Chot Khumpan, a former volunteer and the founder of the Democrat Party, the oldest political party in Thailand still in operation, is one of them.

The 1920s and 1930s are widely considered the golden age of the colonies in Asia, overlooking the impact this circulation of people—and therefore of ideas—between Asia, Europe and Africa had on the colonial systems. After these soldiers and workers returned home, how did their involvement in the war affect their individual destinies, as well as the political, economic, social and cultural future of their people? Some developed personal strategies for benefiting from their experience in Europe, while others founded political parties. The war and the principles of self-determination staunchly defended by both Lenin (The Right of Nations to Self-Determination, 1914) and the US president Wilson (Fourteen Points, 1918) had far-reaching consequences on the political evolution of Asian countries during the interwar period. The circulation of these men contributed to that of ideas and techniques, introducing new socio-professional roles in Asia: skilled workers, pilots, drivers, mechanics, draftsmen, lawyers, journalists, physicians and political activists, all demanding the right to be “Masters of Their Own Destiny.”

The analysis, views and opinions expressed in this section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policies of the CNRS.

_______________________________

The Research Institute on Contemporary Southeast Asia (IRASEC), a CNRS UMIFRE (joint unit with a French research institute abroad) based in Bangkok (Thailand), in cooperation with the Centre for European Studies (CES) of Chulalongkorn University,also in Thailand, is hosting a conference on November 9-10, 2018 on the topic: “Masters of Their Own Destiny: Asians in the First World War and its Aftermath.” Some 20 researchers from Asia and Europe are expected to attend the event, which will be accompanied by a photography exhibition.