You are here

Why Baudelaire Continues to Fascinate

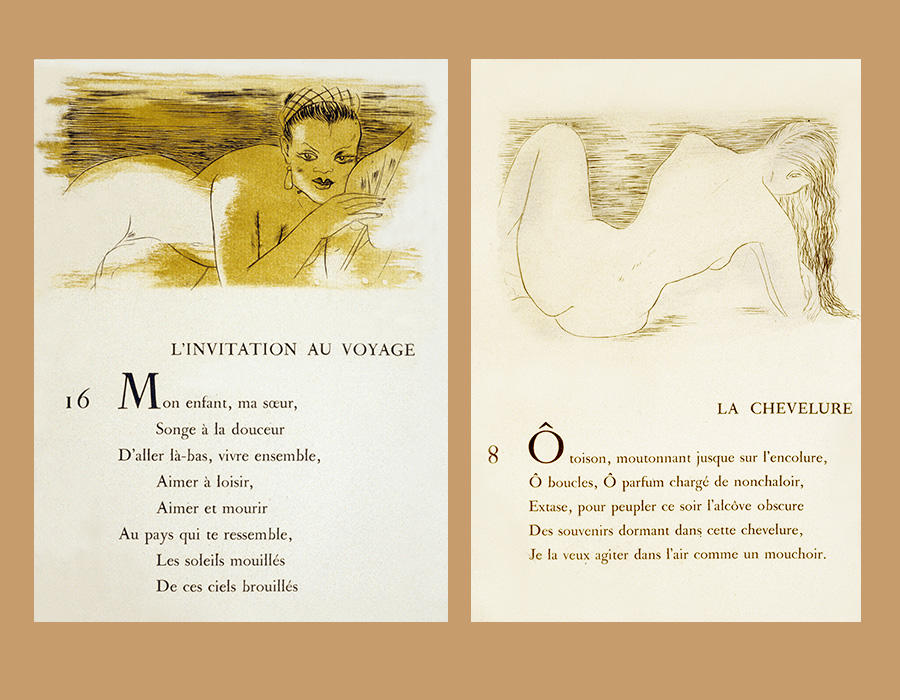

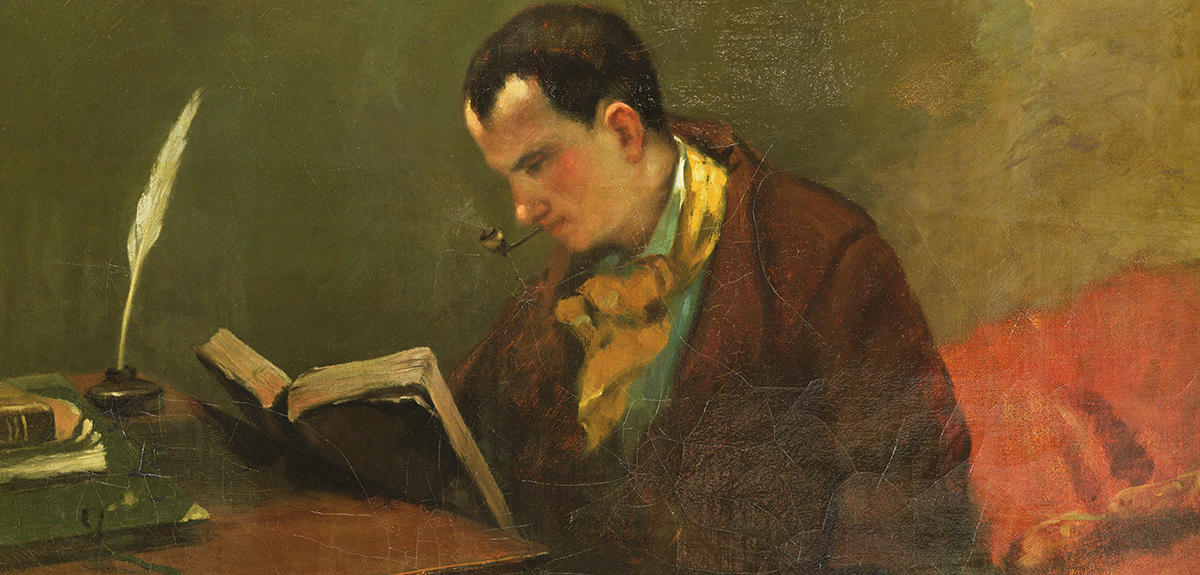

He's a household name, but how can Charles Baudelaire be summed up in a few words?

André Guyaux:1 He can’t be summed up in a few words, but it is worth noting that he was the leading figure of the second phase of Romanticism. He was born in 1821, 20 years after Victor Hugo, and all of his work was dedicated to finding his path in what remained to be explored in Romanticism. Starting with his earliest writings, which were not poetry but art criticism, he sought to define Romanticism: “Intimacy, spirituality, color, aspiration towards the infinite.” He saw in it “the most current expression of beauty,” and made no distinction between Romanticism and modern art.

He also explored the realm of evil, which did not earn him a warm welcome…

A.G.: People quickly recognized his importance, but his works were controversial and his poems were widely condemned. The trial that followed the publication of Les Fleurs du Mal (“The Flowers of Evil”) in 1857 was not due to the sudden displeasure of a few magistrates. It was the result of an orchestrated press campaign denouncing a “sick” book. Even though Baudelaire achieved rapid fame, all those who refused to acknowledge his genius considered him to be dangerous. And there were quite a few: Baudelaire sided neither with the right-thinking bourgeoisie nor with the progressives.

A misanthrope, dandy, drug addict, proponent of drunkenness… He was seen as a scandalous figure in his own time. How is he viewed today?

A.G.: What caused the outrage and brought on the trial was his libertine writings, in particular his poems about lesbianism. The provocative aspects of his personality and his artificial paradises were less of concern. However, his scandalous nature is even more significant now: Baudelaire was the consummate dissident. He remains the ineffable figure of the poète maudit—the cursed poet, whose way of thinking is difficult to grasp. In fact, trying to gain a deeper understanding of what he wrote is what draws all those who continue to conduct research on his work. He cultivated contradiction, he had a taste for paradox, for all things sinuous, while we tend to go for straight lines. Yet we all are fascinated by his depth.

Was that the motivation behind the conference La Pensée de Baudelaire (“The Thinking of Baudelaire”), held in Paris in mid-September2 for the 150th anniversary of his death?

A.G.: Yes, we wondered whether one could discern a philosopher behind the poet, and find a consistent line of thought in his works. Of course, this is subject to debate. For some, the poet is a man of suffering, of dreams, of contemplation—not a thinker. Others see him as an intellectual figure. Baudelaire himself never wrote any philosophical texts as such, but he was the author of several theoretical essays, including one on comedy. He valued the 17th- and 18th-century moralists, and was fond of aphorism himself. In any case, what emerges is a body of thought that stems from 18th-century ideologies and from Joseph de Maistre, but is nonetheless unconventional, essentially dissident.

Joseph de Maistre embodies the counter-revolutionary current of the 1790s…

A.G.: Yes, Baudelaire called him a “clairvoyant” and said that he, along with Edgar Allan Poe, had “taught him how to reason.” But beyond or alongside the fascination that Joseph de Maistre held for him, Baudelaire directed most of his criticism toward progress. He is the ultimate anti-progressive, forever pointing out the damage caused by the progressive illusion, or what he called the “religion” of progress. In the span of a few decades the world had indeed seen the advent of railways and gas lighting, and Baudelaire saw Paris being gutted to build the Grands Boulevards. All this upset and disturbed him. For the first Universal Exposition of Paris in 1855, Napoléon III wanted to have machines everywhere. But Baudelaire could not tolerate that the progressive ideology be applied to artistic creation. For him, beauty is timeless—and so is the artist.

He was a man of his time, and yet Baudelaire continues to inspire many research projects. What kind of influence does he have today?

A.G.: Walter Benjamin, the 20th-century German philosopher and art historian, said that nothing in Baudelaire’s work has “aged.” This is so true that his vision of the world is still enlightening. Generations of writers have claimed to be his followers: Verlaine and Mallarmé to start with, Valéry, Claudel and the surrealists, all the way to Yves Bonnefoy. Closer to us, Michel Houellebecq is an avid reader of Baudelaire. Our conference was attended by researchers of all generations as well as academics from Italy, Germany, the UK, the US, etc… Baudelaire is studied in China, Japan, Brazil: the quintessential Parisian poet has a global audience. In fact, Paris and its cultural services may be the only ones not to have measured his influence.

Can one say that his influence extends beyond the sphere of literature?

A.G.: Baudelaire was obsessed with the idea of modernity. In fact, he gave the word its full meaning. He died too early to see the advent of Impressionism, but in reaction to the watercolors of Constantin Guys he commented, “Modernity is the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent, which make up one half of art, the other half being the eternal and the immutable.” The concept is not easy to explain. For him, modernity was the positive counterpoint to progress: while art is eternal, it is also nurtured by everything new—like photography, whose birth Baudelaire witnessed. Modernity is all of those fugitive elements that art can capture.

But isn’t it also complex, and thus difficult to apprehend?

A.G.: Baudelaire addresses readers from all horizons, sometimes quite remote from the world of literature. A fourteen-year-old can read The Albatross and resonate with his “wings, those of a giant” that “hinder him from walking.” The same is true of his poems on crowds or on the transformation of large cities, one of the phenomena of his time, which he experienced directly. He gives anyone interested in sociology food for thought. Despite their ambivalence, his texts put forth a striking social picture. I am thinking, for example, of Les Petites Vieilles ("The Little Old Ladies"): Baudelaire veers between charity and cruelty, forever in the realm of the undecidable.

Still, aren’t we left with the image of a man who tends to see the dark side of things, which is not really in keeping with the times?

A.G.: In The Voyage (in the second edition of Les Fleurs du Mal), travelers roam the world in search of a change. But at each stop they discover only “the tedious spectacle of immortal sin.” Baudelaire loathed optimism, and that is also what kept him going. He stands as a sentinel against the ever-threatening temptation of naivety. In passing, it is worth pointing out that he could also be the focal point of theological debates. He believed in original sin. He was convinced that evil had an origin and that mankind was indelibly scarred, which inspired him the title Les Fleurs du Mal. And he wanted the frontispiece of his book to feature the Fall of Adam and Eve.