You are here

Tracing Back the Potters of Pompeii

#01 – Monday, 18 November 2018

When we entered Pompeii that morning, the archaeological site was not yet open to the public. The forum was deserted, with Vesuvius looming above it. Vesuvius... the primary figure in our adventure, whose eruption in 79 CE buried Pompeii and its inhabitants, thereby making it the central document of Roman Antiquity.

I’ve been part of missions here for fourteen years now, but the emotions haven’t changed. Strolling through the streets, walking past homes and shops, still gives me a powerful feeling that is hard to describe. The colours change with the seasons, and Vesuvius is sometimes covered in snow. But not on that morning...

I scanned the faces of my mission partners to gather their impressions: Aurore Lambert,1 an anthropologist who is a regular at the site, Lionel Roux, a photographer for the Centre Camille-Jullian, André Desmarais,2 a specialist in forensic science, and Pascale Desmarais, who was one their first mission to the mythic site. What does forensic science have to do with Pompeii? It will actually contribute to a long-term scientific investigation I am conducting of the city’s pottery workshops. This campaign precisely focuses on potters: who were they? We will find out thanks to the fingerprints left on the vases they turned or moulded nearly two thousand years ago. I’ve been aware of this for months, but it is only here that I truly understand that this mission marks one of the last stages of my research on Pompeii’s pottery workshops, which began in September 2012 when I was employed at the Centre Jean-Bérard3 in Naples. This CNRS laboratory created over fifty years ago has, since the 2000s, developed a research program focusing on the ancient city’s crafts and economy. It was established by Jean-Pierre Brun, the former director of the Centre Jean-Bérard and now professor at the Collège de France.

As an archaeologist specializing in the study of ancient ceramics, I study the terra cotta objects that we unearth during excavations: I have to determine their type (bowl, cooking pot, pot...), geographic origin, and dating, as well as where and how these objects were produced. What could be more natural than turning toward the Pompeii site, which at the time was just a few kilometres from my house? This is how the program on the potters of Pompeii came into existence six years ago. Every successive year and campaign provides new pieces for the giant puzzle that we are trying to reconstruct.

#02 – September 2012

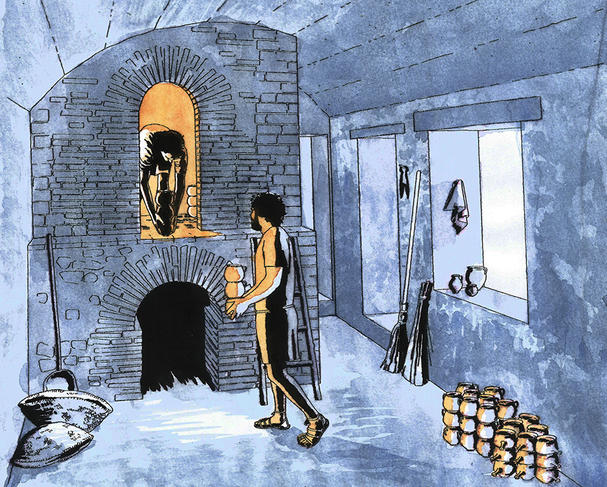

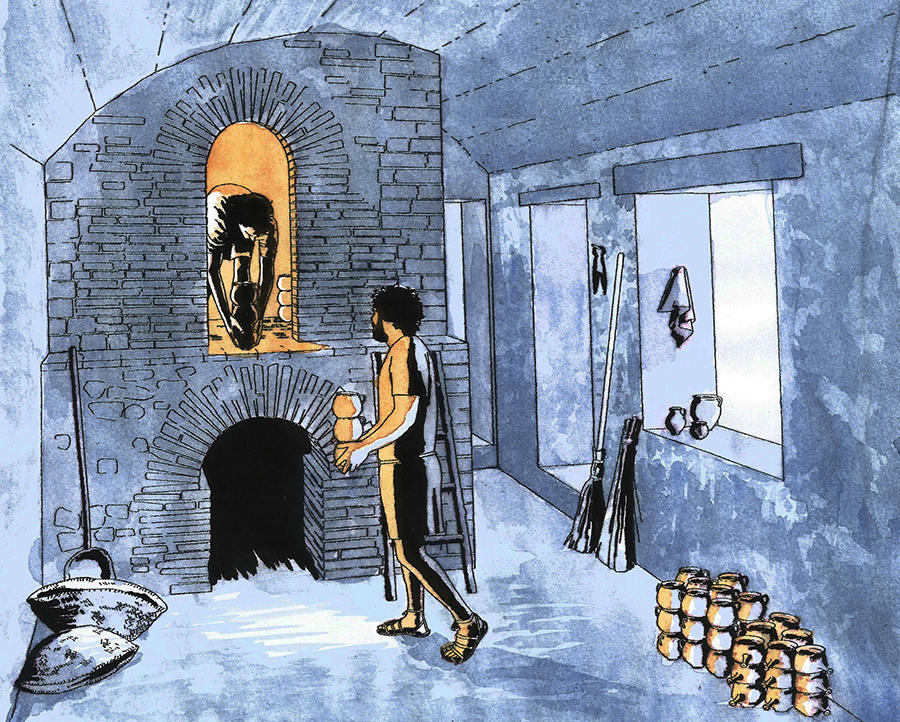

The adventure began with a small team of French and Italian students and archeologists.4 For this initial phase, I logically wanted to revisit the excavation of the first pottery workshop discovered in Pompeii in 1838, which is located outside the city in the necropolis of Herculaneum Gate,5 at the end of a long covered building. It occupies a shop consisting of two rooms on the ground floor. The descriptions of the workshop upon its discovery were cursory: a few pages in excavation journals, or a rare drawing of the kiln in which the vases had been fired. Over time this craft establishment was forgotten by archaeologists and visitors. When we arrived nearly 80 years after its discovery, only the kiln was visible. So what would we discover?

In our first week of excavation we discovered unfired clay vases, covered by the pumice stones that had burst forth with the volcano’s eruption. These vases were produced in 79 CE by potters and placed on the ground awaiting firing in the kiln. The eruption of Vesuvius froze this moment.

We were the first ones to touch these unfired vases after the artisans who produced them!

Emotion swept through the entire team upon the discovery. We were the first ones to touch these unfired vases after the artisans who produced them! They are well conserved enough for us to immediately identify them: they are goblets decorated with small incisions, and covered with a reddish-orange engobe, that the Pompeiians used for drinking.

This discovery was doubly important, for not only did we identify the workshop’s production from the very first days of the excavation, but it was also one of the rare instances of unfired vases discovered in a workshop.

#03 – September 2013

One year after a first fruitful mission (with significant media attention recounting our discovery of the unfired vases), we returned to the same place. And we wouldn’t regret it! We discovered a number of dumps full of vases turned and fired in the workshop; some had production defects or deformations caused by their firing, which is why they were thrown into these pits. Thus began a long-term effort on the part of Aline Lacombe, a ceramologist who works for the Archéologie d’Aix-en-Provence, and myself on these thousands of ceramic vase fragments: cleaning, sorting, object identification, counting and reglueing of fragments, restoration of objects, drawings, photographs! Long hours spent trying to glue together these very small and thin ceramic fragments, whose bellies are less than 0.5 millimetres thick.

But what great satisfaction when these dozens of fragments glue back together, yielding a practically complete vase. We almost felt like we were the potters who’d shaped it. This puzzle provides the entire repertory of the vases produced in the workshop, as well as the chronology of this craft establishment’s activity during the first century CE.

There are a great many goblets, small dishes, cups, small bowls, and an entire series of vases for consuming food and drink. This second mission ended just as well as the first one.

#04 – September 2014

I returned to Pompeii after a year of major changes for me personally, for after over ten years in Italy I returned to France, more specifically to the Centre Camille-Jullian in Aix-en-Provence. This had no effect on the program, which continued in perfect harmony between the two laboratories. For all that, this third campaign was also marked by change, as we enlarged the excavation and set out to verify the state of conservation of two adjoining shops. The first was damaged by an American bombing in 1943, but documents mention the existence of another pottery kiln before that. Upon our arrival the site was overrun by vegetation, so the excavation team took out their shovels and picks and began a major cleaning effort that proved profitable, for we discovered not just one but two pottery kilns! The older of the two had been levelled, but the second one, which was blown up by a bomb that had fallen nearby, was still well conserved enough in places for us to study its construction technique.

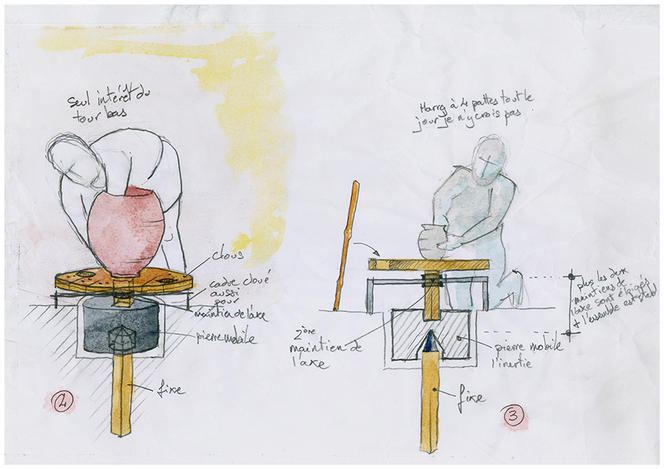

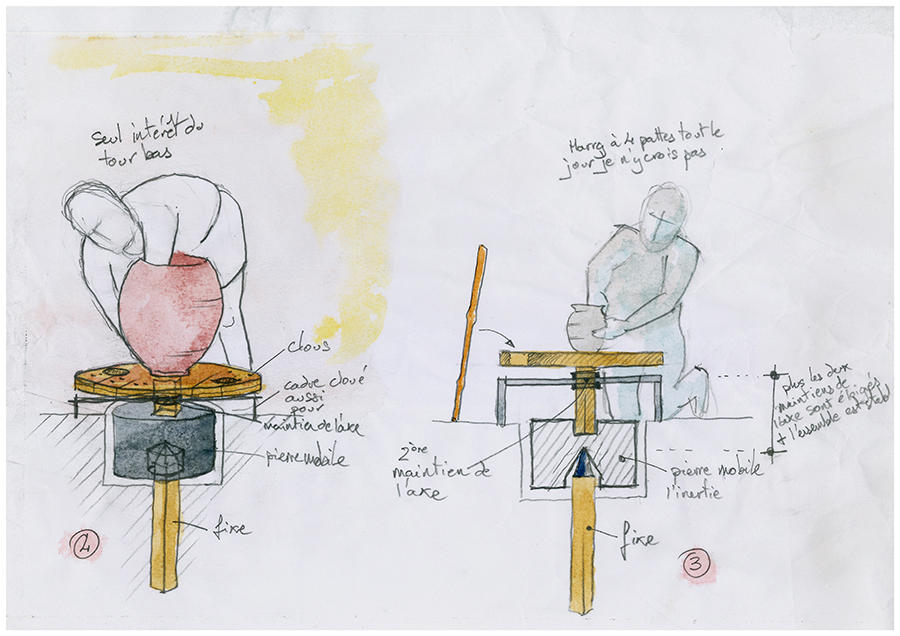

The second shop was intriguing because no apparent traces signalled any kind of craft activity. But like the other explorations, discoveries came quickly. After removing the modern rubble, we unearthed four circular cavities, three of whose walls consisted of fragments of carved amphoras; these were the remains of the potter’s wheels, whose locations we had been searching for and finally found.

This was a major discovery, as it illustrated through archaeological remains what we already knew, but only with regard to frescoes. Among the rare representations from the Roman period illustrating potter’s wheels at work, two are mural paintings discovered in Pompeii. Now we have these Pompeian wheels. While these traces are fleeting, they indicate the location of the master turners as well as the how these wheels worked. We noted the presence of a central axis made of wood on which the turning wheel was placed. The entire chain of operation has now been illustrated, from the shaping of vases, unfired goblets, and the firing of vases in kilns. We know that regardless of what happens afterwards, this campaign has left a mark on our research. Each year, the puzzle continues to take shape.

#05 – September 2015

Like the previous year, we extended our area of excavation, this time west of the preceding area. When we cleared a workshop wall, a tomb appeared! We knew we were in an area of necropolises, but the discovery of the first vase still brought great satisfaction to the team. The tomb was pre-Roman, dating back to the late fifth or early fourth century BCE.

The entire chain of operation has now been illustrated, from the shaping of vases, unfired goblets, and the firing of vases in kilns.

In a coffer made of large stone slabs, the skeleton of a woman was surrounded by vases left as offerings. This discovery (which would be followed by two other graves), explains why the building constructed four centuries later did not extend beyond certain limits, for at the time tombs still had to be indicated on the surface. When the potters set up here, wealthy dwellings and graves stood side by side along a road.

The first fragment unearthed was a vase covered with a black varnish, whose brilliance was revealed in the last rays of sunlight. Then little by little other vases appeared, eleven in total, some with figurative patterns (with figures, animals...).

This is how the field missions for this workshop ended. Setting out from the simple presence of a kiln, we were able to reconstruct a large part of the production chain for ceramics with the discovery of two other kilns, potter’s wheels, workshop dumps, in addition to the production itself.

#06 – September 2016 / September 2017

The importance of our discoveries from the preceding year was quickly noticed. Not only was it a tomb preserved in spite of the area’s bombardment during the Second World War, but it also proved to be one of the oldest ones discovered to date at the site. Thanks to the patience and dexterity of Agnès Oboussier, the team’s restorer, the vase fragments quickly assumed their initial form, and were presented to the public during an exhibition at Pompeii. Needless to say we attacked this new campaign with motivation, especially as it marked the beginning of a new site and study. In Pompeii only two pottery workshops were functioning at the time of the eruption in 79 CE: that of the Herculaneum Gate, which we had studied in the preceding years, and the one located near the Nocera Gate. We moved toward this second workshop in the southern part of the ancient city. This establishment was discovered in the late 1950s; it was used to make oil lamps, which were produced in plaster moulds, as well as small vases, which were made on wheels.

In the second workshop, which was discovered in the late 1950s, oil lamps were made using plaster moulds.

Its history is different but complementary to that of the first workshop. It was set up in a large house after the earthquake of 62-63 CE, which severely damaged the city of Pompeii. The house was reorganized at the time, probably for economic reasons, and a pottery workshop was set up there, including various structures such as a bowl for processing clay and two kilns.

Our excavation helped clarify the workshop’s chronology, for luck was on our side once again! We found a potter’s wheel that hadn’t been identified by the earlier excavators, the fifth one found in Pompeii.

This discovery was satisfying for a number of reasons: we found the same type of wheel as in the previous workshop, but this time we also found the bearing stone and the axle serving as a hub to rotate the wheel. We know enough to attempt a functional reconstruction of this wheel, which is what we are working on with two colleagues who have been part of this program since the beginning, Guilhem Chapelin, an architect at the Centre Jean-Bérard, and Bastien Lemaire, who holds a doctorate in archaeology from the Université de Montpellier-3.

#07 - November 2018

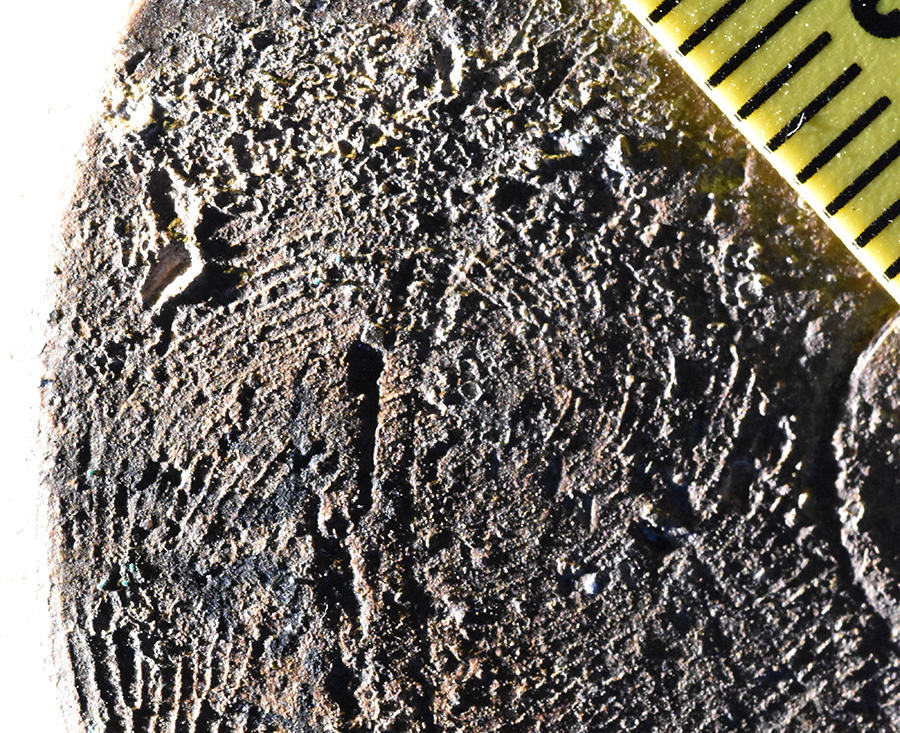

Six years after the discovery of unfired vases, we are now tracing back to the hands that made these objects. This time we’ve come back to Pompeii not to excavate, but to actually identify the potters! This research has taken on another dimension. A year ago I ran into Aurore Lambert, an anthropologist who has been interested in potters for some time, or more specifically in the fingerprints they left on vases. She is developing a research program on fingerprints, and offered to make Pompeii’s workshops into a study case. I accepted without hesitation.

We spent ten days sitting in this storeroom, inspecting each ceramic fragment to detect a fingerprint.

For a number of years, I have wondered about these traces of fingers, which are so moving, bearing witness to the life of the potters. But I didn’t know what to do with them. And here was Aurore proposing to examine these traces in order to identify the people who worked in these workshops, for instance how many there were, their gender, their age. An actual sociological study of Pompeii’s potters. So we met a few months later in the storerooms of Pompeii’s archaeological grounds.

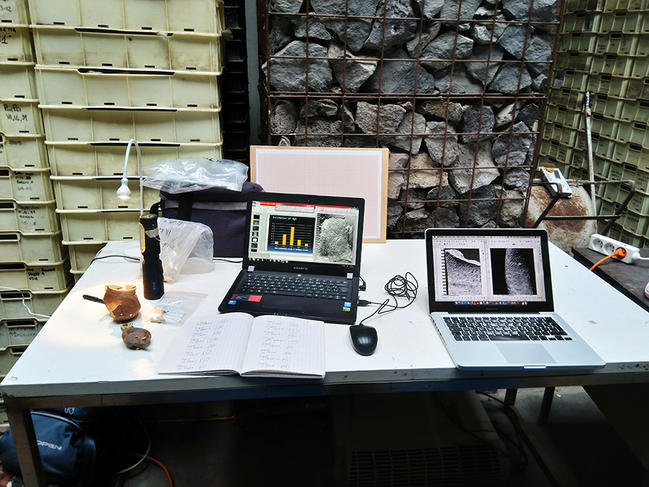

They contain dozens of crates that hold the materials found during the six excavation campaigns: approximately 30,000 ceramic fragments that we had to assess under the guidance of Aurore and the dactyloscopy expert André, who studies identification using fingerprints. We spent ten days sitting in this storeroom, inspecting each ceramic fragment to detect a fingerprint and bring it before the seasoned eye of our partners. Some of them were selected for evaluation, others were placed back in the bag because they were not sufficiently preserved or were too smooth.

The following week we were joined by Celestino Grifa, a geologist at the Università degli Studi del Sannio di Benevento, who collaborates with the Distar (Department of Earth, Environmental and Resources Sciences) of the University of Naples Federico II. We have been working together for a decade in Campania. Like Aurore, Celestino has been examining potters, but his research is more interested in the origin of the raw materials used by the artisans. Where did the clay come from? What type of degreasers were used? We are focusing on his analyses of samples from Pompeii, which helped precisely identify the quarries of extraction. We now know where the clay came from, as the small fossils it contains precisely identified a deposit near Salerno, south of Pompeii.

This final mission also completed the history of Pompeii’s potters. The excavation of the two workshops was now complete; all of the vase fragments had been counted and identified. We now know how the potter’s wheels and kilns functioned. The final image that will be revealed in the coming weeks is the “identity” of our artisans. This identity is entirely relative, for they will remain anonymous, but we will be able to determine the biological gender and age of our master potters. We can thereby have an idea of the social organization of these establishments, which will enrich the history of this craft in Pompeii.

- 1. Eveha – Associate researcher Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS, EFS, ADES, Marseille.

- 2. Associate researcher Aix-Marseille Université, CNRS, EFS, ADES, Marseille.

- 3. CNRS/École française de Rome.

- 4. This research programme is conducted in connection with excavation concessions granted by the Ministero per i beni e le attività culturali, with the agreement of the Parco Archeologico di Pompei, as well as support and backing from the Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères (“Southern Italy” archaeological mission), the Centre Jean-Bérard, the Centre Camille-Jullian, l’École française de Rome, private patrons (CMD2, Art et Luxe, Artfusion, and Arpamed), and Eveha.

- 5. This workshop was excavated as part of a larger programme entitled “Porta Ercolano: organisation, gestion et transformations d’une zone suburbaine. Le secteur de la porte d’Herculanum à Pompéi, entre espace funéraire et commercial,” co-directed by Laetitia Cavassa, Nicolas Laubry, Nicolas Monteix, and Sandra Zanella. It was part of the 2012-2016 five-year program of l’École française de Rome.

Explore more

Author

A ceramologist at the Centre Camille-Jullian, among other responsibilities Laetitia Cavassa manages a research programme on ceramic production at Pompeii through the excavation of potter’s workshops. She also co-organizes workshops.