You are here

The Boom and Bust of Spanish Bricks

Your earliest research focused on the pharmaceuticals industry. What led you to investigate the Spanish financial and real estate crisis?

Quentin Ravelli:1 In both cases, the idea is to follow the “social biography” of a commodity, whether it is pharmaceutical drugs, construction bricks or risk-bearing loans. The way in which these products are developed, produced and then distributed provides a complete overview of the political economy.

For example, in my doctoral thesis I investigated why certain drugs like antibiotics had a paradoxical tendency to strengthen the bacteria that they are meant to combat. In concrete terms, the more these drugs are used, the less effective they become, and the more likely we are to fall ill… I wondered whether other products followed a similar path and came across high-risk mortgages, that are supposed to “democratize” finance and help small property owners. The more money you lend to people who cannot pay it back, the more likely you are to impoverish them, trapping them in a situation of over-indebtedness, until society as a whole can’t withstand it any longer. This spiral was especially devastating in Spain, where an entire “brick economy” was nurtured by loans that were impossible to pay back.

How did the specific case of brick production, the central topic of your documentary,2 end up impoverishing the very people it was supposed to help?

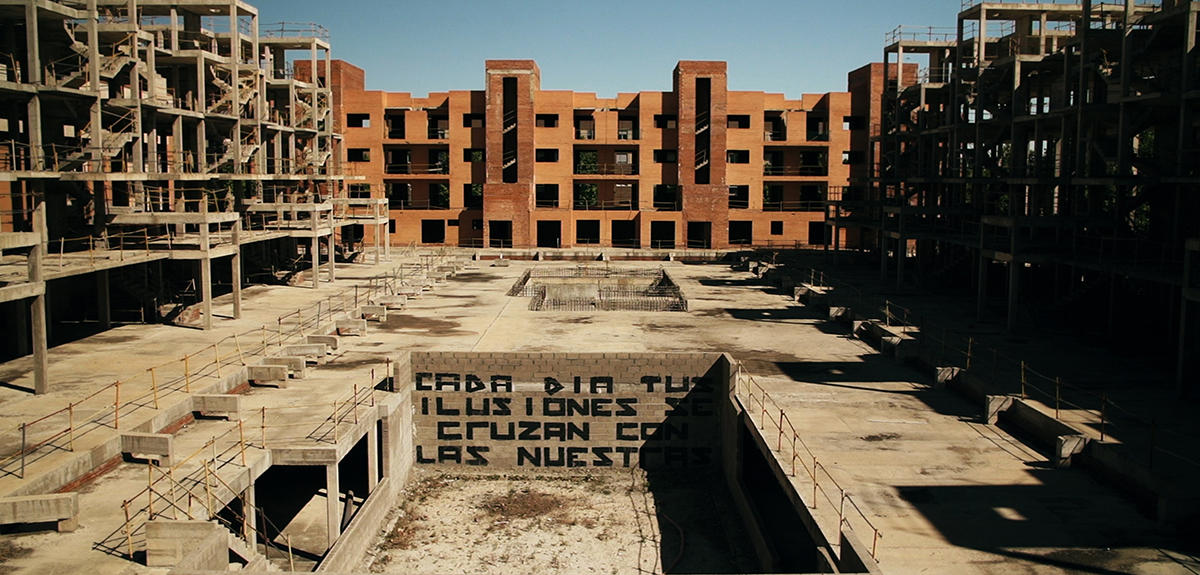

Q.R.: In the 1990s, high-risk mortgages were issued that allowed millions of people—who otherwise would not have become homeowners—to buy an apartment. In Spain this stimulated the construction sector, especially brick manufacturing, which is a national specialty. According to estimates, between 15 and 25% of the country’s GDP was based on this growth model in the 2000s: many Spaniards worked directly or indirectly in construction, and the money they earned building new housing allowed them to borrow money to buy an apartment… It was a closed loop. When the economic crisis hit in 2007 and 2008, the brick factories began to shut down one by one. Many workers lost their jobs and, along with them, their ability to pay their mortgages. Most then tried to sell their property, but in the meantime real estate prices had collapsed. Many found themselves threatened with eviction, due to a Spanish law that allows banks to evict people who aren’t paying their mortgage. In other words, with this situation we can clearly see how a system supposedly conceived to increase access to property (although that was mostly a fallacy) paradoxically led to a wave of evictions.

Why did you choose the medium of the documentary film to tell this story?

Q.R: Film provides visual proof that cannot be conveyed in writing. In sociology, our work consists mainly of reading and writing articles, conducting interviews and analyzing statistics, which of course are essential. But with the documentary, which we use more often in anthropology than sociology, observations of social behavior can be shared, critiqued and compared with others, which enriches the demonstration. For this film, my first documentary, I spent several years following associations like Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca, which is fighting for debt relief for the victims of toxic loans. I tried my best to document, without overlaying any commentary or analysis, the way its members strive to transform their feeling of guilt and indebtedness into collective, politically organized outrage. Telling their struggle in an article or a book is not the same as seeing them on the screen, banding together to prevent an eviction by the police, invading a bank to demand the cancellation of a debt, or quite simply supporting each other in a meeting. In fact, I’m still thinking about the best way to link the scenes on film to the scientific articles, which are based, for example, on a questionnaire answered by 600 over-indebted people in 12 Spanish cities.

The film also includes many scenes in a brick factory…

Q.R.: I wanted to emphasize the fact that there is no clear line that separates an “abstract” financial system and the supposedly more concrete industrial economy. Toxic loans obviously played a major role in triggering the global economic crisis. But in Spain, the crisis also involved a classic case of overproduction: the country produced more bricks than it could realistically sell. It’s all interlinked.

These sequences show how bricks, the raw material for building entire new cities, have played a key role in the Spanish economy for decades, and why the factories now find themselves forced to stop production or even destroy their stock. Here again, the thing that had brought them wealth—not incidentally a fundamental product in human history and in civilization—was transformed into a burden that had to be disposed of, to try to limit the damage as much as possible. In addition, bricks are interesting as a cinematographic object because they show us the tangible raw material that our economy is made of, reminding us that even high finance is rooted in a much more concrete reality than we often imagine.

Are you going to continue conducting research on the issue of debt, perhaps even in another film?

Q.R.: I have just published a companion book to the documentary, Red Bricks, which gives a sociological narration of the stages of the economic crisis as it evolved during filming. Many of the dialogues and interviews in the book are based on raw footage that I didn’t use in the documentary, an approach that may interest other researchers in the social sciences. But generally speaking, I would like to delve more deeply into the role of emotions in social movements. One unique aspect in Spain is that so much of the population fell prey to toxic loans, which at the same time made them all the more united in fighting the banks and demanding the cancellation of their debts. The population’s strong unity and capacity to reverse the feeling of guilt seems to have been a spearhead for movements like the Indignados and Podemos, which subsequently succeeded in becoming part of the electoral process. This is nearly unheard-of for social movements. I have other ideas for films, but in particular I’d like to help sociology take advantage of the visual culture that has been booming in recent years, and which opens extraordinary new possibilities for scientific research.

- 1. Researcher at the Centre Maurice-Halbwachs (CNRS / EHESS / ENS Paris). Quentin Ravelli has also published a book on the subject: Les briques rouges. Dettes, logement et luttes sociales en Espagne, éditions Amsterdam, août 2017.

- 2. This film was produced by Survivance (Carine Chichkowsky) with the participation of Cécile Bodénès (principal photography), Catherine Mabilat (editing), Alvaro Silva (sound), Thierry Mazurel abd Yann Pittard (music). It was coproduced with CNRS Images with support from the CNC, the Île-de-France region and the Casa de Velázquez (French academy in Madrid).

Explore more

Author

Fabien Trécourt graduated from the Lille School of Journalism. He currently works in France for both specialized and mainstream media, including Sciences humaines, Le Monde des religions, Ça m’intéresse, Histoire or Management.