You are here

Plants adopt new strategies to survive in cities

Is it true that wild plants, faced with the destruction of their natural habitat, are increasingly present in cities?

Pierre-Olivier Cheptou:1 It is difficult to identify general trends, since there is a wide range of different situations. In Montpellier southern France for example, you find relatively common plants that are also present everywhere in the surrounding countryside. But things are not the quite same in the northern city of Lille, which can be home to colonies of rare species. This is due to the context, and in particular to the agricultural conditions: wild species have become heavily depleted in field crops in northern France, and find in cities some kind of refuge.

Despite this, it would be a mistake to think that urban environments are the solution to conservation problems! In France, farmland makes up most of the available surface. Yet it has lost 75% of the insect biomass over the past thirty years. The reason why we think wild species are on the rise in urban areas today is probably that our perception of cities has changed. In fact, wild plants have always been there. We just weren't aware of them, since cities were mostly seen as unnatural places.

How do plants adapt to the urban environment?

P.-O. C.: Organisms are able to adapt fairly quickly to the specific conditions of cities, which are characterised by rising temperatures, the increasing scarcity of pollinators, and fragmentation, i.e. the fact that plant habitats are broken up into small patches because the ground is mostly concrete. This is true for instance of Crepis sancta, a wild plant that grows in the soil at the base of street trees. In such a situation, it seems there is little advantage for a plant to disperse its seeds, since it is extremely likely that they will end up on concrete and be lost. As it happens, this is precisely the strategy adopted in cities by these plants, which spread their seeds less widely.

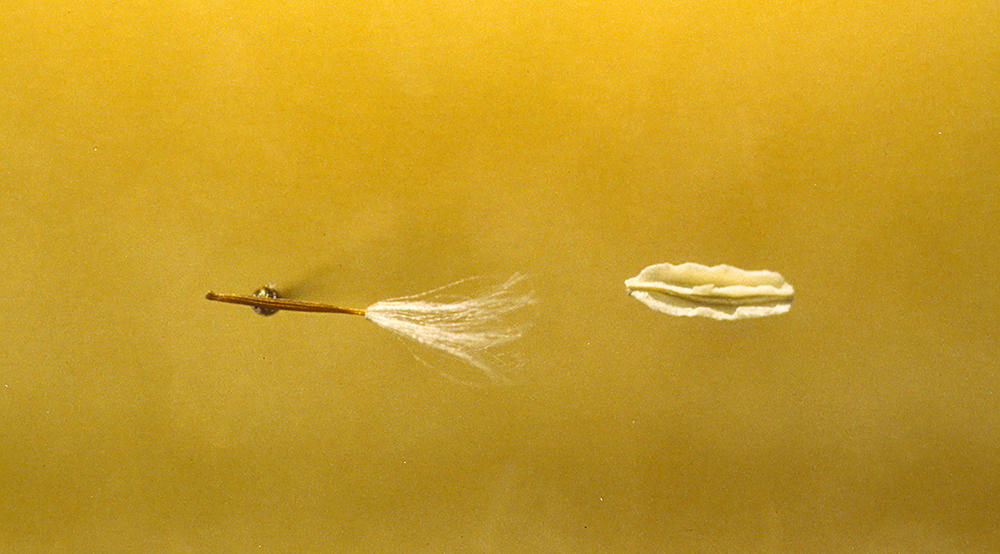

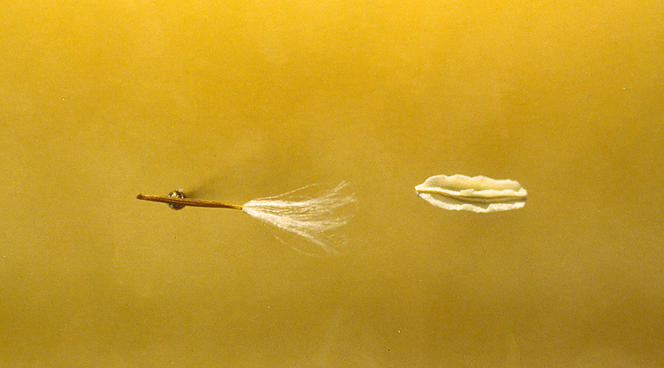

We came to this conclusion by comparing specimens of Crepis sancta from beneath street trees with populations from the countryside of Montpellier, a few tens of kilometres from the city centre. This species produces two types of seed: small ones that are easily blown away by the wind, and large ones that fall closer to the plant and are not dispersed. In the city, the proportion of large seeds has increased to 15% of the total, as compared to 10% in rural areas. The change we observed took place over fifteen generations, in other words in the space of fifteen years, since this is an annual plant. This is an example of what is known as rapid evolution, a phenomenon only discovered in the last thirty years. In his version of evolution by natural selection, Darwin didn't believe that such rapid adaptation was possible.

Is the evolution of species always good news?

P.-O. C.: Not necessarily. For example, you might think in the first place that it's a good thing for plants to disperse their seeds less, and therefore have more offspring. But if there is a mass extinction in a city (or elsewhere in a fragmented habitat), such as a severe drought that wipes them out, there will be no seeds left for recolonisation, precisely because the plants will have lost the ability to disperse them! This means that short-term evolution is not necessarily beneficial in the longer term, on larger spatial scales.

I also study the effect of pollinator decline on plant pollination systems. We hypothesise that, in order to survive, plants adapt by doing without pollinators and making use of self-fertilisation (since they are generally hermaphrodites). There is evidence of a breakdown in the interaction between plants and pollinators due to an increase in the plants' self-fertilisation rate. This is a very worrying trend, because if the right sanitary conditions for pollinators are met in agricultural environments, the plants may not provide them with enough nourishment. It means that the relationships within the ecosystem are changing. Moreover, while a higher rate of self-fertilisation can save plants in the short term, it is not necessarily good for their survival over time. On evolutionary scales, species that adopt self-fertilisation systems have never had a very bright future. Such a strategy could therefore be their undoing.

You explain that studying the adaptation of plants in urban environments is highly instructive from a more global point of view.

P.-O. C.: Indeed. I don't believe that we should view cities as specific ecosystems but rather as an ecological model for the study of more general issues. We can use the characteristics of urban environments to understand certain processes and changes that are more far-reaching. For instance, it is warmer in city centres, and in this sense, cities act as a model of global warming. In Montpellier, temperatures are three degrees warmer in the centre than outside, which roughly corresponds to the forecasts for 2050 in the region. I therefore use this temperature gradient to have a better idea of how plants are adapting to climate change.

Cities can also help shed light on other ecosystems affected by habitat fragmentation, and this reflects many natural situations. For example, there are similarities between Crepis sancta in their urban grass patches, and observations of island flora by botanists in the 1960s. Admittedly an island is much larger, but the situation is the same regarding seed dispersal: if they spread too far, they fall into the water. So plants are likely to disperse less.

How can cities become more wildlife-friendly?

P.-O. C.: By staying put! If we want to see natural processes in cities, we must allow the mechanisms of colonisation, reproduction and so forth to take place. In fact, over the last few years, there have been changes in the way plant species are managed in urban centres. In the past neatly laid out flower beds were in fashion, whereas plants are now given far more freedom. So-called ‘weeds’, i.e. spontaneously-growing vegetation, are left to grow pretty much everywhere, and pose no problem to local residents. In Montpellier, for instance, the tendency is to encourage natural processes, with initiatives that aim to be less interventionist. An example of this is late mowing, which not only enables plants to reproduce and thus promotes pollinators, but also allows them to be eaten by herbivores such as insects or other species. This boosts biodiversity in cities with encouraging results, but we must bear in mind that other types of environment are just as important for biodiversity conservation.

- 1. Pierre-Olivier Cheptou is a CNRS research professor at the French Research Centre in Ecology and Evolutionary Ecology (CEFE – CNRS / EPHE / IRD / Université de Montpellier).