You are here

Peter the Great, a Tsar who Loved Science

Some 300 years ago, nearly to the week, the Russian tsar Peter the Great (1672-1725) left France after a visit that proved memorable—for the best and worst reasons. For two months, this unpredictable guest sabotaged the plans that had been made for his stay and rode roughshod over the etiquette of Versailles.

An atypical monarch

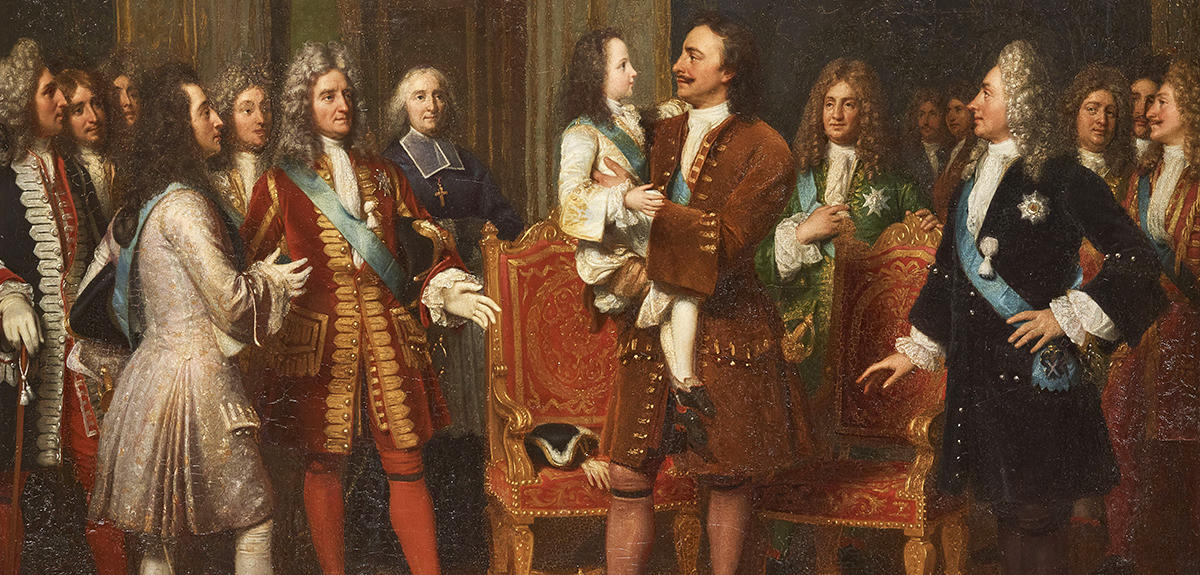

“Peter’s entire reign was like this diplomatic visit, during which he flouted protocol, for example by picking up the seven-year-old King Louis XV in his arms to kiss him, shocking the court in the process,” reports Francine-Dominique Liechtenhan, senior researcher at the Centre Roland Mousnier1 and scientific consultant to the exhibition “Peter the Great, a Tsar in France, 1717.” “Throughout his 43 years in power,” Liechtenhan adds, “Peter strove to transform his country in every way, creating a permanent army based on conscription (all muzhiks were subject to compulsory military service for 25 years), pursuing a policy of territorial expansion (by the end of his reign, Russia stretched from the Baltic to the Pacific and the Caspian Sea) and moving the capital from Moscow to Saint Petersburg, to bring it geographically, economically and intellectually closer to Western Europe.”

In keeping with that principle, this giant of a man, all of two meters (6’7”) tall, allowed every Russian to climb the social ladder on the basis of merit. At the same time, he encouraged the founding of some 200 factories and many schools (military, technical, medical, etc.), reduced the influence of the Orthodox Church and even changed the physical appearance of his subjects by banning beards and caftans (the traditional long—and very warm—coats) for men and requiring women to dress in the Western style. “Even though he governed by constant improvisation, and left Russia weakened by endless wars and a lack of effective national administration, Peter propelled the world’s largest country into the modern age, placing it among the leading continental powers,” Liechtenhan recounts.

A passion for science

An atypical ruler in every way, the tsar who proclaimed himself Emperor of All the Russias in 1721 also had a keen interest in science and technology. At the age of 15, fascinated with compasses and astrolabes (instruments used to track the movement of the Sun and stars above the horizon), he was taught their use by Franz Timmerman, a Dutch seaman versed in astronomy. Timmerman also instilled in the young prince a love of mathematics, geometry, military architecture and ballistics. Another Dutchman, the shipbuilder Karsten Brandt, instructed him in the art of navigation. “As a teenager, Peter was given the equipment to learn blacksmithing, carpentry and stonemasonry,” Liechtenhan says. “In all, he mastered some 15 manual professions, which was unthinkable for a French or English monarch.”

His travels in Europe, incognito when necessary under the name Peter Mikhailov, allowed the tsar—and tremendous admirer of Alexander the Great—to assuage his thirst for the sciences, meet with the learned thinkers of the day and stay abreast of the latest technological advances.

His first westward journey (and the first foreign trip by any Russian sovereign), from March 1697 to September 1698, enabled him to broaden his knowledge of artillery in Prussia, work for four and a half months as an ordinary shipyard hand, learn the basics of surgery in Holland, tour the foundries of Germany, attend a session of the Royal Society, train a telescope on Venus at the Greenwich Observatory, or even make coffins with an English carpenter…

A whirlwind of activity

On his second visit, which lasted just over 20 months (January 1716 to October 1717), Peter stayed in France for many weeks, including 43 days in Paris. According to Liechtenhan, “this journey, whose primary purpose was to gain recognition for the Russian conquests around the Baltic Sea, was a diplomatic disaster. On the other hand, the tsar used the occasion to give free rein to his libido sciendi (desire for knowledge). In this sense, his stay on French soil was a whirlwind of activity.”

Fleeing the elaborate, punctilious ceremony of the court, the 45-year-old tsar visited the Paris Observatory no fewer than three times, examined the scale models of the fortifications built by Vauban at the Louvre, strolled the Jardin des Plantes botanical gardens, and admired the curios in the collection of Louis-Léon Pajot, Count of Onsenbray, who was the country’s Postmaster General and the designer of an anemometer. Rising at dawn, and flanked by interpreters as he spoke Dutch and a bit of German but very little French, Peter also took care to visit such institutions as the Sorbonne, the Royal Printing Office and the Gobelins tapestry works, asking questions to the workers and dyers, and expressing his awe at the sight of the gears, cogs and rods of the Marly Machine, the hydraulic installation built to supply water for the fountains of Versailles.

Hoping to fill his travel trunks with scientific instruments, he did the rounds of workshops like that of Jean Pigeon d’Osangis in Place Dauphine, where he bought a mechanical celestial sphere calibrated as per the Copernican system.

In order to bring French know-how and craftsmanship back to Russia, he recruited more than 60 carpenters, upholsterers, carvers, decorators, etc. (not always the most highly skilled, as the French government did not want to lose its finest specialists), who joined his entourage for the journey back to the newly founded Saint Petersburg.

First sovereign at the Academie des sciences

Knowing that the best way to learn from scientists was through direct personal contact, the tsar arranged meetings—in their homes or in his apartments—with the chemist Geoffroy, the botanist Lémery, the geometrician Varignon, the physician Duvernoy, the physicist Reaumur, among others. One of the highlights of Peter’s time in Paris was his participation in a session of the Académie Royale des Sciences, whose members offered him demonstrations of various machines and chemical processes. To show his own manual abilities, he impressed the audience by shaping a piece of ivory on a lathe. “On December 27, 1717, he was named an extraordinary member of the Academy, “making him the only monarch, along with Albert I of Monaco, to have been granted such an honor," Liechtenhan reports. Most importantly, the distinction convinced him to create a comparable institution in Russia. Among the first scientists, all from other countries, to sit as members of the Imperial Academy of Sciences were the French geographer Delisle, the Swiss physicist Bernoulli and the Swiss mathematician Euler. Peter the Great’s intellectual curiosity made him a genuine exception among the crowned heads of his day.”

- 1. CNRS / Paris-Sorbonne Université / Huma Num / EPHE.

Explore more

Author

Philippe Testard-Vaillant is a journalist. He lives and works in south-eastern France. He has also authored and co-authored several books, including Le Guide du Paris savant (Paris: Belin) and Mon corps, la première merveille du monde (Paris: JC Lattès).