You are here

“Mein Kampf remains invaluable for understanding Nazism”

The reprinting of documents from the past is essential for studying history. How did you approach the transcription of a book so charged with symbolism?

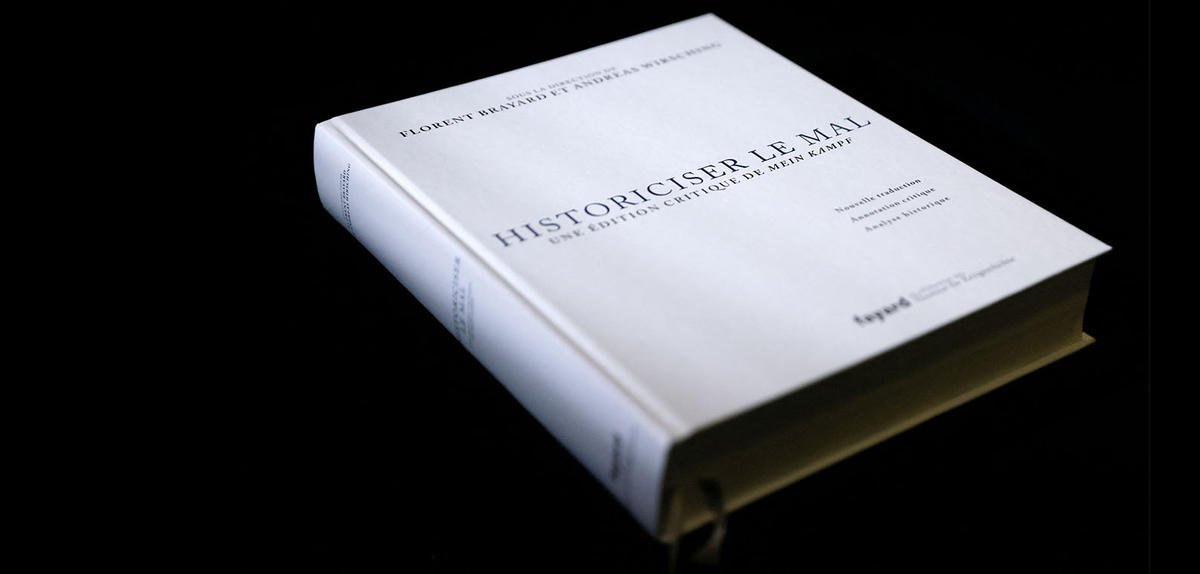

Florent Brayard:1 We approached it in the same way as any other historical source, but making an extra effort, given the stakes involved, to be painstakingly thorough. First of all, we needed our French translation of Mein Kampf to be as accurate as possible. Then we adapted the exceptional critical annotations compiled by the Leibniz Institute for Contemporary History (IfZ).2 Lastly, we went one step further than our German colleagues, offering not only a long general introduction, but also a specific preamble to each of the volume’s 27 chapters. As a result, Historiciser le Mal is actually three books in one, each of equal importance: a new translation of Hitler’s text, a body of critical commentary comprising 2,800 notes, and the introductory texts.

When Fayard, the publisher, announced this project in 2015, many people spoke out against drawing attention to Mein Kampf. Are such objections valid in the age of the Internet?

F.B.: I don’t think so, in the sense that Hitler’s book was already widely available. The 1934 edition was sold for decades and, more importantly, anyone could download a digital version at the click of a mouse. In other words, Mein Kampf was already massively present, but in deeply unsatisfactory forms. We wanted to offer, for the first time, a critical and scientific edition – a common practice for all major historical sources. No one can dispute the role that Mein Kampf played in the violent history of the 20th century. I am happy that our book was ultimately very well received when it was released last June, including by most of our critics. Reason, and I would dare add science, triumphed in the end.

Mein Kampf is a book of no particular genre, combining biographical, programmatic and ideological elements. How did Adolf Hitler write it?

F.B.: Other than the mostly narrative chapters at the beginning of the first volume, in which the author recounts his childhood and his participation in the Great War, Mein Kampf is very badly written, repetitive and a chore to read. In it Hitler develops a populist message that consists in offering simplistic and misleading solutions to complex problems. His goal was to convince the reader of the veracity of a number of precepts: that there is a ‘racial’ hierarchy, with the ‘Aryan race’ at the top; that the Jewish ‘race’ was responsible for both the world’s troubles and Germany’s defeat in 1918; that Germany needed to conquer a ‘living space’ at the expense of the Slavic populations; that parliamentary democracy should be abandoned, etc. This is the Nazi ‘worldview’ that we know only too well, since it tragically guided Hitler’s policies after 1933. But all of these components were already clearly defined in 1925-26.

How did the translator and the scientific team work together?

F.B.: We were fortunate enough to work with Olivier Mannoni, and to share with him a high standard of professionalism that required us to devise new working methods. The important thing was to ensure that the final text was as accurate as possible, without improving on the original German in any way. To that end, we revised his first draft together, line by line, striving to make it less literary and as close as possible to the source, with all of its many flaws.

In education, will this new edition allow secondary school teachers to renew and expand the study of Mein Kampf?

F.B.: I certainly hope so! It was primarily with them in mind that we undertook the project. With the critical notes and introductions, they will have all the information they need to formulate a consistent presentation. In fact, Fayard has made one-tenth of the print run – 1,000 copies – available free of charge upon request to libraries and learning resources centres. This also palliates the price problem: a 900-page large-format book is necessarily rather expensive. Eventually we will also offer an online version, no doubt in partnership with the IfZ. And speaking of teachers, the French Holocaust Memorial wants to host training sessions on the use of Mein Kampf in secondary schools, which is an excellent idea.

Although Hitler did not initially think of Mein Kampf as a political programme, it later became an instrument of political propaganda. In what way does it remain a vital document for understanding Nazism and the genesis of the Holocaust?

F.B.: In 1925 Hitler was at a low point in his life. His putsch had failed miserably, he had been convicted and imprisoned and his party was disbanded. However, the very fact that he embarked on such an ambitious literary project shows that he still hoped to have the means one day to implement his racist, authoritarian and warmongering ‘worldview’. Mein Kampf is in a sense the description of a Utopia – the Nazi Utopia that Hitler wanted to bring about. Hence its strong programmatic character. After all, the book advocated, among other things, the elimination of parliamentary democracy, the eradication of political parties, the dissolution of the labour unions, remilitarisation, the invasion of Poland and then of the USSR, the persecution of Jews and the adoption of a eugenicist policy. Concerning the Holocaust the connection is less direct, because Mein Kampf does not specifically call for the murder of Europe’s Jews. Nonetheless, the author puts forth what I would call ‘categories of thought’ that would allow him, when the time came, to develop this genocidal policy, in particular by describing Jews as the enemy within that must be neutralised should they become a threat.

Historiciser le Mal can be seen as a tool for deconstructing Nazi ideology. How does this critical edition help the reader to untangle the religious, mythological, political and philosophical references in Hitler’s text?

F.B.: One of the best things about the German critical edition is that it shows how Hitler’s line of thinking was nothing new. On the contrary, it reworks ideas that had already been in circulation for decades, or even centuries: neo-Darwinism, völkisch thought, racial theories, pan-Germanism, anti-Semitism in its religious and then racist manifestations… Thus our edition also allows readers to place Hitler’s thinking in its context, showing how much it owes to its times. In the mid-1920s, and in some cases for decades before then, certain political groups perceived the world in purely racial terms. Hitler clearly followed in their footsteps.

Some claim that focusing on the importance of Mein Kampf runs the risk of promoting Hitler-centrism, drawing attention away from the everyday agents of Nazism. Is this a genuine danger?

F.B.: No one claims that Hitler single-handedly invaded Poland and then the USSR, at bayonet point, or that he built the famous autobahns with his bare hands! Obviously, the Nazi phenomenon resulted from deeply rooted dynamics involving many contributors. Even so, there is no reason to deny or minimise Hitler’s role in this catastrophe. Without him, Nazism could not have arisen in that form, nor would the appalling radicalism of the Third Reich have been conceivable. That is why it’s so important to have available, at last, a critical edition of Mein Kampf. After all, no other dictator before or since has ever taken the trouble to describe what he wanted to do in such detail. His book is therefore an irreplaceable source for understanding Nazism.

Could reading this book arouse new anti-Semitic sentiments, or is Mein Kampf only ‘preaching to the choir’?

F.B.: I don’t think that Mein Kampf, in and of itself, could turn a non-politicised reader toward racism or anti-Semitism. It was written 100 years ago in a convoluted style and has lost any persuasive power – especially in our critical edition, which provides the reader with every safeguard. That said, there is no doubt a small group of readers, neo-Nazis or extreme rightists, who derive some satisfaction from reading the book. But why would they buy our volume, which is costly and consistently denigrates their idol, when they can easily get the older editions in a bookstore or on the Internet? Our work is not intended for them, but rather for all those – teachers, researchers, students, history buffs – who sincerely want to know more about Hitler and Nazism and thus gain a better understanding of how they laid waste to all of Europe, marring the image that we had harboured of our own humanity. We are operating on the premise that it is possible to historicise evil. Now it’s up to our readers to form their own opinion.

Historiciser le Mal, une Édition Critique de Mein Kampf, Florent Brayard and Andreas Wirsching (eds.), translation by Olivier Mannoni, Fayard, June 2021, €100.

- 1. Florent Brayard is a historian and a CNRS senior researcher at the CRH (Centre de Recherches Historiques – CNRS / EHESS) specialising in the Nazi policy of persecution and extermination of Jews.

- 2. The German edition, supervised by Christian Hartmann and three other historians under the auspices of the IfZ in Munich, was published in January 2016.