You are here

Is Science in Crisis?

Conspiracy theories and fake news, a phenomenon that was reinvented in recent years, are spreading today through social media. Are we in the midst of a knowledge crisis?

Mathias Girel:1 No, science itself is more solid than ever in its demonstrations, predictions and applications. The crisis lies in the fact that knowledge and expertise are devalued. In particular, there is a certain distrust of "regulatory" science. I believe that ongoing developments prevent most people, except for a narrow circle of researchers in a discipline, from distinguishing as easily as they once did between robust science and other approaches that simply resemble it.

What is it today more so than before that prompts doubt among the non-specialists that we all are, even while reading an honest press or consulting expert reports?

M. G.: Firstly, there is a phenomenon of one-upmanship, in which scientific advances are oversold by some media, including the most reliable. When the public sees a sensational announcement fizzle out over time, it makes it more difficult to know what to believe afterwards. Another reason is connected to conflicts of interest in scientific expertise, with recent studies showing occasionally blatant financing bias. One such study revealed that expert assessments financed by the agri-food industry are four to eight times more often favourable to the sponsor than those with independent sources of financing (link is external)! Another reason is ghost writing, which was recently brought to light with respect to glysophate or the pharmaceutical industry: researchers accept to sign their names to publications written by other entities, laboratories, or firms, thereby cheapening the symbolic value of their institution. So-called "philanthropic" foundations—sometimes referred to as philanthrocapitalismFermerSponsorship by powerful players that apply the principles of capitalism. Bill Gates (former CEO of Microsoft), Mark Zuckerberg (CEO of Facebook), Gordon Moore (co-founder of Intel), and Eric Schmidt (former CEO of Google) have invested hundreds of millions of dollars in foundations they created, which finance research on oceans, genetic diseases, the environment, astronomy, etc. They have subsequently become new actors in scientific production within the research landscape. to emphasize their profit-making mode of operation—also come into play. Although they are well-advised, because they seek to eradicate a particular disease, such as polio, their action deeply disrupts the smooth running of research.

How does this philanthrocapitalism financed by the private sector disrupt the research landscape today?

M. G.: The research agenda is set by the senior management of philanthropic organisations. In other words, a handful of people can decide to disengage from a field of study overnight if its visibility or prospective short-term results are not optimal—unlike French public research actors (CNRS, Inserm, Inra, etc.) who operate with a broader management, national committees, and longer deadlines. For that matter, you have a greater chance of securing funding from these patrons if you work on subjects that match their criteria , such as the ocean floor, astrophysics, AIDS, or cancer. Certain authors, and this remains to be verified, believe that there is even financing bias depending on the illness. In the United States for instance, where capitalist philanthropy is very present in the form of foundations, they claim that it is easier to finance research on melanoma, of concern to the white population, than on sickle cell anemiaFermerGenetic disorder linked to an abnormality of hemoglobin, producing sickle-shaped red blood cells that cannot travel through capillaries, the narrowest blood vessels., which mostly affects blacks.

Haven't these factors that cloud scientific discourse (media hype, conflicts of interest in expert opinion, and philanthrocapitalism) always existed?

M. G.: Yes, to a certain extent, although their impact is greater today. For example, the social media intensify the phenomenon of hype in the press, which sometimes, sadly, needs it to survive. Conflicts of interest in expert evaluation, although already described by the physicist Richard Feynman back in the 1970s, are now widely revealed to the general public. Private financing of research through philanthrocapitalism, on the other hand, is much higher than it was during the 19th and 20th centuries. This explains why we are today in a sort of grey area, in which it is difficult to attribute motives to certain actors in research and its dissemination. More precisely, we are prompted to ask ourselves the question of intention, whereas we should only be interested in the truth or falsity of publications, expert opinion, or evidence.

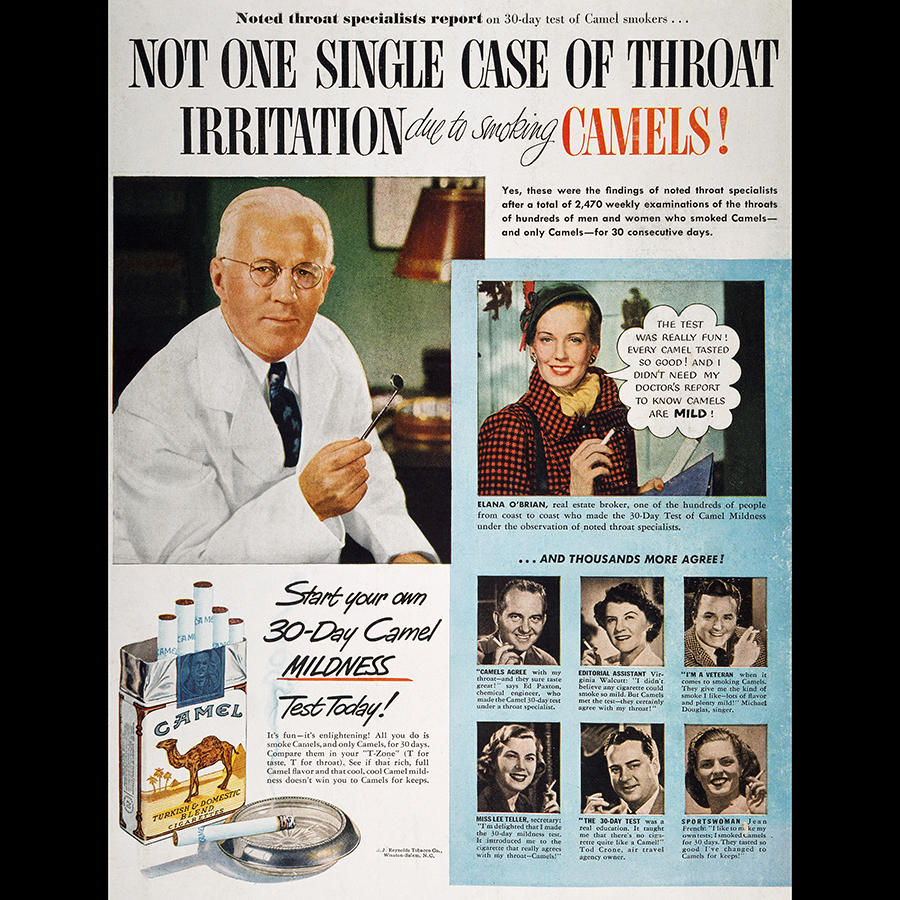

Regarding hidden intentions, we can cite the example of cigarette manufacturers, who in the 1950s and ensuing decades successfully cast doubts on the dangers of tobacco by financing studies that can in no way be called into question on scientific grounds.

M. G.: Precisely. They simply financed research on causes other than cigarette smoke in an effort to explain lung cancer: viruses, the impact of dust, genetic determinants, etc. In Golden Holocaust, published in 2012, the historian of science Robert Proctor showed that it is very difficult to challenge these studies or to dismiss them using the traditional arguments on the dividing line between science and non-science, as they meet all of the traditional criteria: they come from scientists, they are based on scientific formalism and method, they are published in peer-reviewed journals, and meet the Popperian argument on refutabilityFermerAccording to the philosopher of science Karl Popper (1902-1994), a theory is scientific if the propositions that make it up lead to the deduction of at least one empirical statement that would refute it if verified. For example, "if a deviation of light from distant stars was not observed near the Sun, the theory of general relativity would be untenable.", etc.

Only the intention underlying this research can convey its "pathological" character, as it was financed with the sole aim of dismissing, suppressing, or minimising the most important cause of lung cancer, which is tobacco smoking. This kind of elucidation takes time, and shows that the scientific criteriaFermerSeries of criteria that distinguish scientific from non-scientific activity. These include refutability, peer review, publication in peer-reviewed journals, and the replication of results. currently available to distinguish between pathological and "normal" science are less effective than before.

The replication of results, which is one of these scientific criteria, has precisely experienced a crisis in recent years.

M. G.: There is indeed a crisis in the reproducibility of results, particularly in biology, social psychobiology, and medicine. Is this due to the pressure researchers face to publish quickly ? Or is it instead a symptom of the deteriorating quality of research being conducted today? Or perhaps it's a sign that the replicability of an experiment is not as decisive a criterion as previously believed for evaluating the scientificity of research? The phenomenon raises many questions. In any event, it is important to be wary of certain interpretations whose only goal is to belittle sciences as a whole, as seen recently with the smearing of environmental protection agencies. Finally, it is important to remember that replicability is not the be-all and end-all, as data gathering campaigns in real conditions outside the laboratory are not always replicable, nor are studies conducted over decades using cohorts, for instance of patients. It would therefore be risky to dismiss them on these grounds.

How can the scientific criteria that distinguish science from pseudoscience be improved?

M. G.: Whether it involves publications, scientific reports or expert opinion, we can no longer limit ourselves to examining a single publication or isolated report. Of course this can help identify obvious cases of false science, but I believe it would be useful to recreate the context in which research is being carried out. This makes it possible to find out for example whether it is part of a programme extending over ten or twenty years, whether it involves exploring other causes, takes into consideration the multifactorial aspects of a phenomenon, or the state of knowledge in preceding decades. Only the humanities and social sciences, and the historical approach in particular, can fill this gap in the natural sciences, and thereby help defend the knowledge and scientificity of a particular field. Naturally, these analyses over the long term will not be the sole prerogative of researchers, as investigative journalists have quite often produced exemplary inquiries.

Cigarette manufacturers have deviated public attention, the sugar lobby accused fats of causing cardiovascular diseases. What other examples of the intentional production of "pathological" science can be cited?

M. G.: I would add climate change deniers, who use mathematical tools, especially statistical correlations, and take a line that cannot always be easily dismissed using standard arguments regarding the truthfulness of the evidence, even though the overwhelming majority of published science contradicts it. Among them is the US physicist Fred Singer, who has devoted himself to finding flaws in the research conducted by the IPCC2 or other communities of climatologists. It seems to me that a researcher, think tank, laboratory, or institution that produces nothing but negative proof or the rebuttal of scientific evidence over a period of five to ten years, without ever identifying a new cause or leading to novel predictions, clearly shows a denial bias. The historical approach that I am proposing will not replace the traditional criteria used by the scientific community, but provides an additional analytical tool over the long term. To illustrate the issue of intentionality, the philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe cites a telling example: a man activates a pump that fills a house's water tank; but the water is poisoned, and the house is occupied by Nazi leaders whose eradication would prevent some of the horrors of war. Tightening the focus on the man's sole muscular movement makes it impossible to understand his action.

The focus must therefore be widened in order to understand hidden intentions.

M. G.: Yes, but not too much! This is precisely the tendency of conspiracy theorists, whose vision is so broad that they lose ordinary perception of actions. Absolutely everything relating to their subject of interest them is seen through the lens of a hidden intention. The ordinary meaning of actions no longer exists for them.

How then can this conspiracy theory bias be avoided?

M. G.: I don't have a magic formula. But conspiracy theories can often be dismantled by referring to the very definition of conspiracy, which is the "explicitly coordinated action of a small group acting toward morally or legally reprehensible ends unbeknownst to most."3

Each term contributes to showing that large-scale conspiracies are highly improbable, for three reasons. First, the condition "unbeknownst to most" means that the action must remain secret (at least until it succeeds), which is all the more difficult when the "group" in question is large. It therefore appears unlikely that "freemasons," "Jews," "the media," etc., the usual figures brandished by conspiracy theorists, be capable of keeping such secrets. Secondly, the group in question must pursue "coordinated action", its members must share a common intention, and carry it through. The comparison is trivial, but think of how difficult it is to organise a family gathering! Imagine what it would be like with 1,000 or 10,000 actors. More seriously, this relates to the distribution of intention within the group.

The philosopher of science Karl Popper, who was a harsh critic of conspiracy theories, believed that social phenomena are no more than the aggregate of individual motives, and cannot be explained by collective intention. We must nevertheless admit that there are indeed many intentional actions on the part of NGOs, governments, etc., and that common purposes can be found in some fields. This second criterion thus represents an improbable but not impossible condition.

What is the third reason why large-scale conspiracies are unlikely?

M. G.: The scrutiny of outside parties, who want to know your motivations. In the context of a large-scale conspiracy, the actions carried out necessarily have public effects and do not withstand critical examination. Robert Proctor, who unveiled the hidden intentions of cigarette manufacturers, based his efforts on 80 million pages of archives (made available by tobacco companies from the 1990s), and traced powerful actors who financed certain sectors of research. In the face of such heavyweights, irrefutable demonstration was essential: Proctor was summoned to court dozens of times as an expert witness, and his evidence was never refuted. Of course, it should be noted that in order for there to be a conspiracy, it must be proved that the revealed intentions have caused the events observed, which is not always the case. For example, if I really want a particular singer to win the Eurovision song contest, and it actually happens, my intention is by no means the cause of it.

Does this calling science into question risk harming its already damaged image in the eyes of the general public?

M. G.: I don't think so. As I explained, there is no question of considering these issues from the angle of a conspiracy theory, which would result in harsh skepticism—and distrust of anyone or any authority. It's more about being grateful to these organisations for conducting research or protecting our health and the environment, among other things, while making sure to identify their weaknesses, which change with time and context. The production of ignorance, whether it be pathological science, conspiracy theories, or fake news, prompts us to reflect on the role of knowledge in our societies and the value we ascribe to it, and how the institutions we establish are aware of their blind spots and the types of attacks they may suffer. I am of course convinced that knowledge is absolutely key to an informed citizenry that can rationally and reasonably discuss and question any subject, including political measures.

Explore more

Author

Science journalist, author of chilren's literature, and collections director for over 15 years, Charline Zeitoun is currently Sections editor at CNRS Lejournal/News. Her subjects of choice revolve around societal issues, especially when they interesect with other scientific disciplines. She was an editor at Science & Vie Junior and Ciel & Espace, then...