You are here

Is Menopause a Social Construct?

We learn from your book, La Fabrique de la Ménopause (“The Menopause Factory”),1 that the term “menopause is rather recent, and that it originates in France. What was the context behind its creation?

Cécile Charlap:2 A French doctor, Charles de Gardanne, coined the term in 1821, at a time of growing interest in women’s health issues. From the 18th century onwards, with the revival of the Enlightenment, the rise of natural science, categorisation and rationality, a bi-categorical concept of the body emerged, according to which males and females were seen as different and opposite entities.

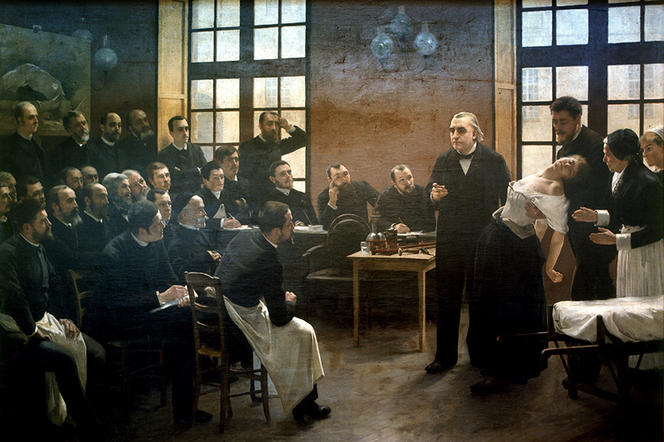

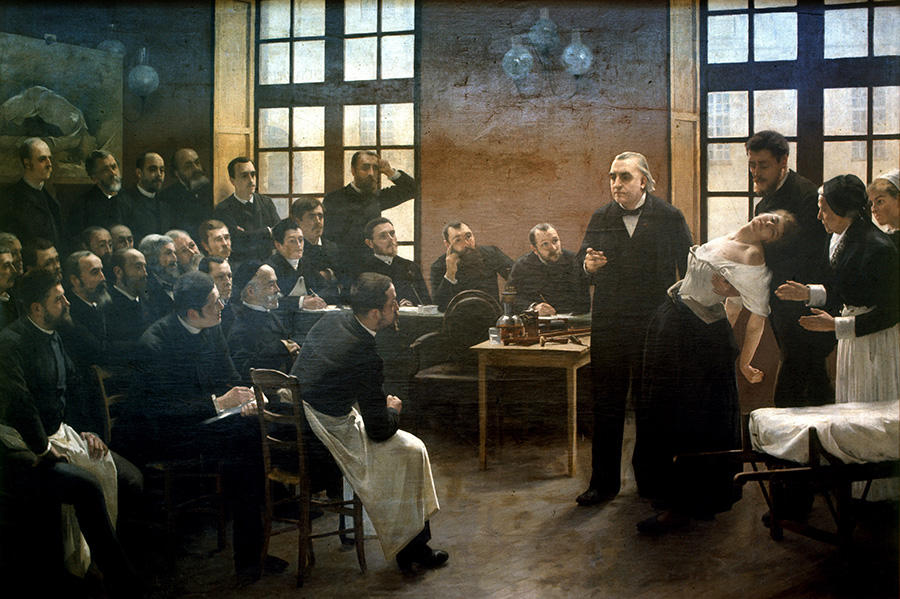

Until then, the female body was considered a lesser version of its male counterpart but within the same continuum. For example, the term “climacteric”, inherited from antiquity, was used to qualify this critical turning point in human ageing, thus not at all specific to women nor focused on the end of menstruation and fertility. This new construct of female biology continued throughout the 19th century. With the rise of psychiatry, and in the context of Charcot’s “Theatre of Hysteria”, menopause was even thought to be a cause of mental illness and kleptomaniac or sexual frenzy.

It is also a Western concept. You explain that in the Japanese tradition, for example, there is no word for menopause…

C.C.: The anthropologist Margaret Lock has shown that, before the 1990s, there was no equivalent Japanese term to describe the end of fertility and menstruation. A word, konenki, encompasses ageing in general, for both women and men: hair greying, stiffening of the joints, etc. This reflects different representations of the body: while it is perceived as eminently individual in Western society, for the Japanese, it harbours a kind of vital energy, the ki, which is related to other people, to the community and, more widely, to the cosmos. It is also about diverging perceptions of fertility and maternity. In the Western world, to be fertile means to give birth, whereas in Japan the concept extends to the child’s upbringing. The grandmothers interviewed by Lock felt that they were still fertile because they took care of their grandchildren.

The concept of menopause was founded on the notion of pathology, featuring in medical literature that set forth a rhetoric of decline. But in your view, symptom, deficiency and risk are like the “Three Fates”…

C.C.: Menopause is a word used by doctors, interpreted within a medical framework and associated with three main indicators. The first is the symptom, which forms a kind of grammar of the body that women learn in the course of their life. In the 19th century, menopause was associated with an impressive string of symptoms, from hot flushes to a propensity for alcoholism… Today the symptomatology has evolved, but still includes a host of physical and psychological indications.

The second factor is deficiency, the notion that menopause is not a hormonal transformation but a loss, defined according to a standard corresponding to women’s hormone levels during the years of fertility, as though the fertile body were the norm. Lastly, the third indicator is risk – of cancer, osteoporosis – and in general an alteration of quality of life, as though this were specific to menopause and not ageing.

The notion of menopause has also evolved along with medical progress…

C.C.: In the early 19th century, when the concept emerged, the body was thought to be ruled by “humours”. Menopause was explained by a lack of strength among older women: they became too weak to expel menstrual blood, and this blood retention was believed to cause many disorders, including cancer, inflammation, polyps, ulcers, etc. Physicians prescribed bloodletting and the application of leeches, treatments that were deeply rooted in their era. In the mid-19th century, doctors advised menopausal women not to ride bicycles or travel by train, reflecting the prevailing prejudices about the dangers of speed.

Then, at the turn of the 20th century, a hormonal conception of the body gradually took hold. Menopause was then considered a disease resulting from oestrogen deficiency, a notion closely related to the development of synthetic hormones by the pharmaceutical industry, culminating in the 1960s to 1980s. More recently, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) has been losing momentum on the Western market since two studies3 established a link between this treatment and cancer, but it has been booming in Asia since the 1990s.

This pathological approach creates a highly negative image of feminine ageing. What does that say about the representations of women and social relations between the sexes?

C.C.: My theory is that the construct of menopause is firmly anchored in gender-based social relations and the hierarchy of masculine and feminine, according to which the male body is considered essentially stable and in the realm of reason, while the female body is the domain of “nature”, suffering and instability.

Our conception of menopause, which reinforces this perception, introduces the idea of an ageing process that starts earlier and is marked by more deficiencies for women than for men. We can see this in the public arena: for example, the French Senate is full of grey-haired men revered for their experience and maturity, while the female body is perceived more in relation to fertility and highly valued looks. Thus, the emphasis on sterility and the alteration of physical appearance gives rise to representations of female ageing which mean that, for women, to age is to lose one’s social value. This is quite obvious on the dating market, where women lose their worth much more quickly than men.

This image is also influenced by certain representations of menstrual blood…

C.C.: The representations of menopause are linked to those of menstruation. In the West, menstrual blood is seen as special. In art history, for example, blood flowing from a wound features in thousands of paintings, but menstrual blood is taboo. While a woman must have that blood to be considered a woman, she must also conceal it. Furthermore, starting from adolescence, women are made aware of the necessity of medical supervision of this blood and the body.

This medical framework shapes women’s personal experience in what you call a “learning path”. What exactly is that?

C.C.: The experience of menopause is not only physiological – it is also social, because it is something you learn, most importantly in interaction with a physician. All of the women I’ve met have talked about it with a doctor, who plays the role of an educator, presenting a list of symptoms that will serve as a checklist for understanding the body.

Yet menopause is only one episode in a socialisation process that begins with puberty. Learning to monitor the body, whether for menstruation or managing contraception as part of a couple, is mostly a woman’s responsibility. It would not occur to any parent to ask their son whether he has sperm, or take him to the doctor’s to talk about it, whereas a woman’s body and genitality are investigated and made part of her medical check-ups from an early age.

In the 19th century, the medical literature recommended that menopausal women abstain from sex. Today, women are advised not to become pregnant after the age of 40. In addition to physiological menopause, you talk about “social menopause”. What do you mean by that?

C.C.: I tried to show that the moment when women stop having children does not coincide with physiological menopause. Originating in the medical and media narrative, another form of sterility – social this time – occurs long before then. Conception after the age of 38 to 40 is seen as exceptional. In the medical literature, specific chapters are dedicated to these so-called “dangerous” or “high-risk” pregnancies, which are therefore discouraged. The media calls them “late” and suggests they must be justified, thus establishing a standard of declining fertility starting at the age of 40. In comparison, paternity after that age is not considered unusual and when a male celebrity has a child after the age of 60 or 70, their age is not an issue.

Based on the interviews that you have conducted, would you say that the menopause norm is imposed more on women from urban and/or affluent backgrounds?

C.C.: The corporeal manifestations do not only affect a woman’s body, but also her interactions with others. Women from urban backgrounds who occupy executive positions or whose jobs involve contact with the public will experience hot flushes as a stigma, because they suddenly reveal what is ordinarily hidden – redness, perspiration, odours, etc. – in places (in town, on public transport, in the office…) where such things are not expected, thus impairing a woman’s self-image. In order to “maintain face”, to use Erving Goffman’s expression, these interviewees prove more likely to resort to hormone therapy in order to relegitimise the body whenever balance of power is at stake.

In your book, you often refer to the theatre, the “staging” of menopause, which is the subject of extensive media coverage (health websites, magazines, TV shows, etc.) and commands a large audience. Could you summarise this “play” for us?

C.C.: The media narratives on menopause are all quite similar: they feature a woman, the main character of a play called “Menopause”, with a first act focusing on the perimenopausal “chaos”. Hormones are presented as active entities affecting women, destabilising their bodies and psyches.

Act two is a kind of echo chamber for the medical narrative on the symptoms, which are as exaggerated as wide-ranging, from vaginal dryness to itchy skin and hard-to-style hair, in addition to depression and loss of libido. This apocalyptic situation is resolved in the third act by an admonition to regain the upper hand and control over one’s body, through medication, nutritional practices, exercise or sex. This course of action for menopausal women recalls that currently advocated for the elderly, who are exhorted to be dynamic, physically and socially active, etc.

You have observed that, outside of the medical domain, the only acceptable way to talk about menopause is either in jest or as an insult…

C.C.: When I looked at narratives on menopause over several years, I noticed that the only truly acceptable way to talk about it was medical, with health professionals. Other than that, in everyday life or in the media, there are only two other modes of expression. First of all, humour, which is used to evoke unpleasant, hurtful situations or to convey a message couched in laughter, as Jean Duvignaud observed. The other mode, which was emphasised by the interviewees, is the insult, heard or felt – “Just like a menopausal woman!” This says something about the representations and the undercurrent of violence that can be associated with the very term menopause.

What do you think of the recent emergence of the concept of andropause?

C.C.: It’s a notion that is very interesting to observe but slow to take hold. Generally speaking, the male body, genitality and contraception have been the subject of much less research. The female anatomy is always more scrutinised, exposed and closely monitored. I think that the emergence of andropause in the medical and institutional literature needs to be investigated – along with, more broadly, the way masculine fertility is perceived.

Reading

Cécile Charlap, La Fabrique de la Menopause, CNRS Éditions, February 2019, 272 pages.

- 1. In French, CNRS Éditions, 2019.

- 2. Cécile Charlap is a senior lecturer at the Université de Toulouse Jean-Jaurès and a researcher at the Interdisciplinary Laboratory Solidarities, Societies, and Territories (LISST) laboratory (CNRS / Université Toulouse Jean-Jaurès / EHESS / École Nationale de Formation Agronomique).

- 3. The US study “Women’s Health Initiative” (WHI), published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, 2002, 288(3):321-33, and the UK Million Women Study (MWS) published in 2003 in The Lancet 362(9382):419-27.