You are here

In Ethiopia, Lalibela's Mysteries

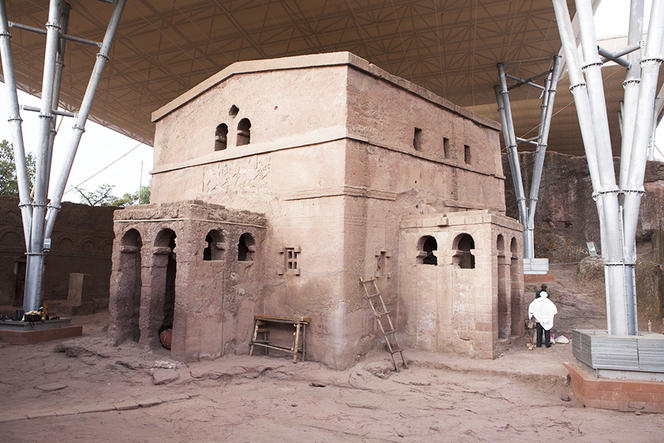

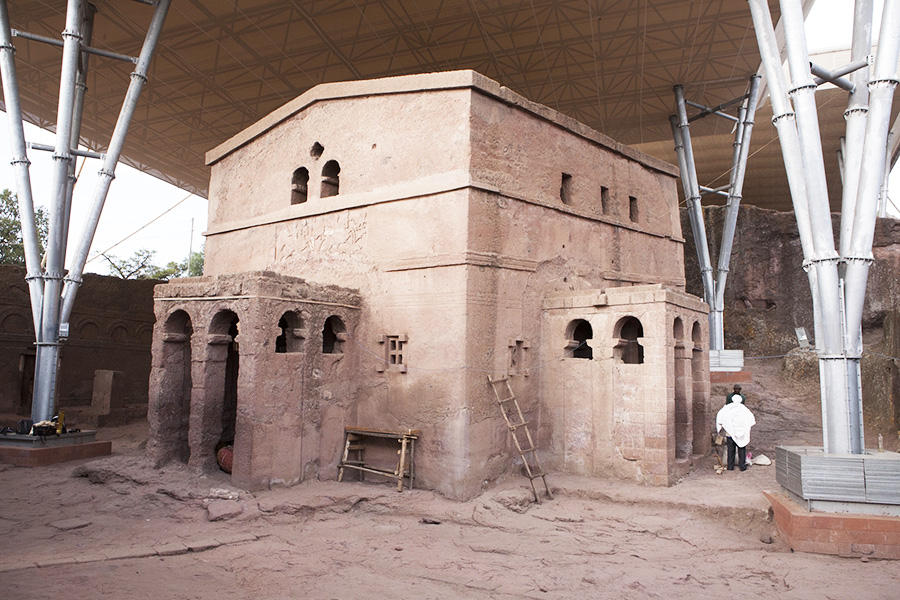

The rock-cut monolithic churches of Lalibela never fail to prompt the curiosity and admiration of tourists. This site nestled atop Ethiopia’s high plateaus, 500 kilometres north of the capital Addis Abeba, is a destination for hundreds of thousands of pilgrims, who for centuries have been thronging to these sacred sites, considered to be a holy land for Christians of the Ethiopian Church.

Aside from its spectacular architecture—which UNESCO recognised as a World Heritage Site in 1978—Lalibela is remarkable for its complexity. “There are many rock-cut churches throughout Ethiopia,” explains Claire Bosc-Tiessé, an art historian at the CNRS and scientific advisor at the INHA (Institut National de l’Histoire de l’Art). “But such a concentration of buildings in such a small space is entirely unique.” With its tangle of churches, trenches, underground galleries, and immense rooms carved into the rock, Lalibela is like no other known site, and therefore raises many questions.

The historian Marie-Laure Derat, a specialist in medieval Ethiopia, has also asked herself these same questions. The two researchers naturally combined their efforts in an attempt to find answers. “The site is so famous that we're under the false impression that we know everything about it,” explains Derat, a senior researcher with the laboratoire Orient et Méditerranée.1 “We ultimately know little about its history, origins, or role in Ethiopian society.”

In an effort to make their research project a reality, they took full advantage of their assignment at the Centre français des études éthiopiennes2—a joint unit with a French research institute abroad (UMIFRE) and the successor of the archaeological mission backed by the National museum, created by the French at the request of the Ethiopian government during the 1950s—to launch the Lalibela Mission in 2008. Lalibela? The site takes its name from an Ethiopian king who made it the centre of his kingdom in the 13th century, and gave it its emphatic religious dimension. His reign and character left a strong impression, as Lalibela was considered a saint approximately two centuries after his death, with the site beginning to receive its first pilgrimages. Yet information about how it was created and administered was sorely lacking.

The two researchers began their investigation by drawing up a precise map of the site, which allowed them to make a first observation: the relics that have survived demonstrate that there were multiple sequences of successive digging. Some churches actually have a door or stairway leading nowhere, showing that the original structure disappeared. Others show improbable outlines, suggesting that they were laid out in accordance with pre-existing edifices.

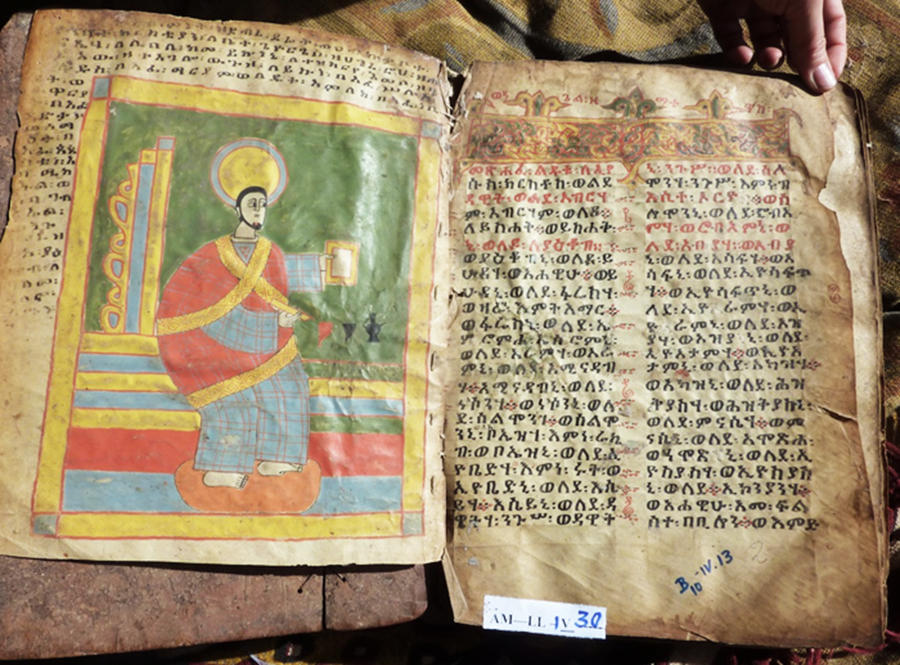

Since the rock does not allow for dating the buildings, research has concentrated on all other available traces, including an important body of manuscripts, paintings, and various objects found in churches. “There are no sources for the period before the 13th century,” Derat points out, “although they are very revealing from that period onwards.” A key role in this history is played by a small portable wooden altar, which bears a dedication, in the classical Ethiopian language of Ge’ez, from Lalibela himself, stating that the object is a gift to the church.

The manuscripts, written in the same language, confirm that it was at the initiative of this same king that the religious complex was founded. “The archives we possess never discuss construction work,” Bosc-Tiessé notes, “but they are very clear with regard to property, relating that King Lalibela gave land to the clergy so that they could benefit from it.” This form of organisation was all in all fairly similar to certain monastic orders established in Europe during the same period. “At the same time, these documents demonstrate the king’s omnipotence in the political system,” Derat adds. “He is the one who possesses land and disposes of it at his discretion, and who also regulates the life of the Church, its institutions, and clergy.”

As the picture became clearer with the completion of this research, a new discovery came along and expanded knowledge of the site. During excavations, the archaeologists and their teams identified a tremendous amount of rubble that the workers had piled up as they dug into the rock, a genuine goldmine for archaeologists. “This rubble includes traces that predate the 13th century, suggesting that the Lalibela site was inhabited before the founding of the religious complex. We found animal remains, as well as traces of hearths and ceramics, both signs of domestic occupation.”

Excavation of the rubble also revealed that it was sitting atop traces of older buildings, which were most probably meant to disappear in favour of churches. The leaders of the Lalibela Mission see this as additional proof of the existence of a powerful society around the 10th or 11th century, one that was capable of constructing imposing buildings comparable to fortresses, for instance. All of these new signs are so many pathways towards understanding an Ethiopian society and culture about which we know virtually nothing, and that coexisted with the kingdom founded in the 4th century CE, always more or less attached to Christianity.

“We now know enough to construct a scenario,” Derat concludes. “A powerful elite occupied the site around the 10th century, building substantial infrastructure. In the many tombs that are still accessible, the orientation of bodies reveals that there were Christians at the time, but also many non-Christian subjects. During the 13th century Lalibela moved to the site, and engaged in an energetic assumption of power by transforming some buildings into churches and carving out new ones. Incidentally, this coincides with a period in which the kingdom expanded towards the south.”

Over the course of excavations, knowledge regarding more recent time periods also emerged. That is the paradox of such rock-hewn edifices, for unlike a traditional archaeological site, the oldest traces were erased as stone carvers reworked monuments. In addition, over the centuries the occupants of the premises always dug deeper in order to strengthen the foundations of the churches, which are threatened by the rock’s friability when in contact with water. “We can already conclude that the site continued to evolve until very recently, which is to say up to its inscription on UNESCO's World Heritage list,” underscores Bosc-Tiessé.

This represents a millennium in the history of a country that has had intense relations with the Eastern and later the Western worlds since antiquity. The research possibilities are immense for these two historians, beginning with the complete excavation of the rubble remaining from the hollowing out of the churches, which they would like to pursue. However, two difficulties complicate their task. The first is the location of this rubble, which is in the middle of the site, precisely where pilgrims converge. This means that they will have to work the old-fashioned way, with a pail and a pickaxe, as the use of machinery would be too intrusive at these sacred sites. “People are interested in our excavations, and have generally been kind, but things can change very fast.”

The other factor relates to politics. Since October, the Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has shown great interest in the site, whose conservation he actively supports. The two researchers believe that there is a need to make research central to the measures, in order to recommend appropriate restoration and development operations that do not endanger these final vestiges of the past.