You are here

Bringing Mandela’s Voice Back to Life

It’s a room charged with history, still echoing with the voice of Nelson Mandela. Fifty-two years ago, in the Pretoria Supreme Court, the anti-apartheid leader and seven of his companions were sentenced to life in prison. The hearings of the so-called Rivonia Trial, recorded on vinyl cylinders, had never been completely digitized due to the fragility of the medium—at least until now. The Laboratoire de Recherche Historique Rhône-Alpes (LARHRA)1 successfully performed this delicate task, and on March 17, 2016, in that same courtroom, president Laurent Vallet of the French National Audiovisual Institute (INA) presented a digital version of the recordings to the South African Minister of Arts and Culture, Nkosinathi Emmanuel Mthethwa. “It’s a way to keep history alive,” said 82-year-old Dennis Goldberg, one of the three former defendants present that day, along with Ahmed Kathrada and Andrew Mlangeni.

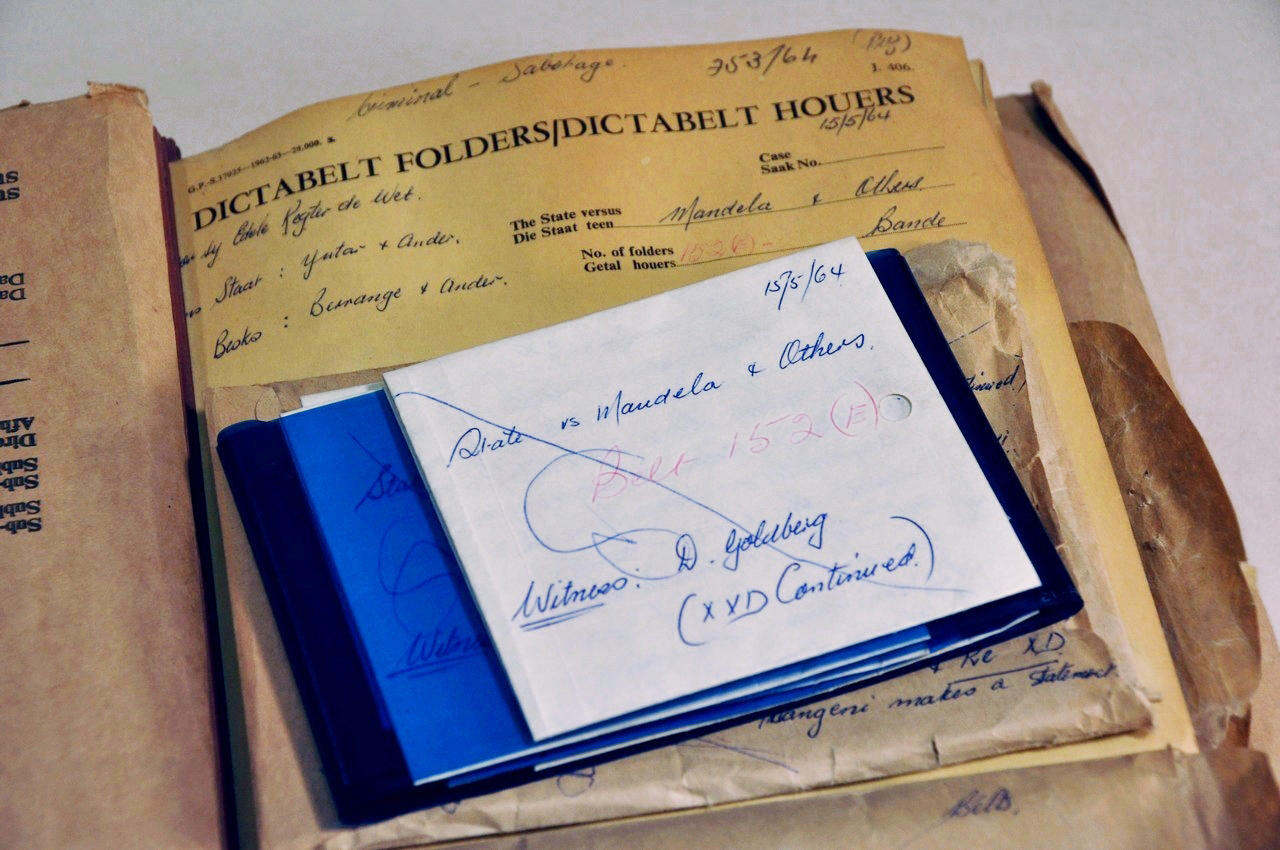

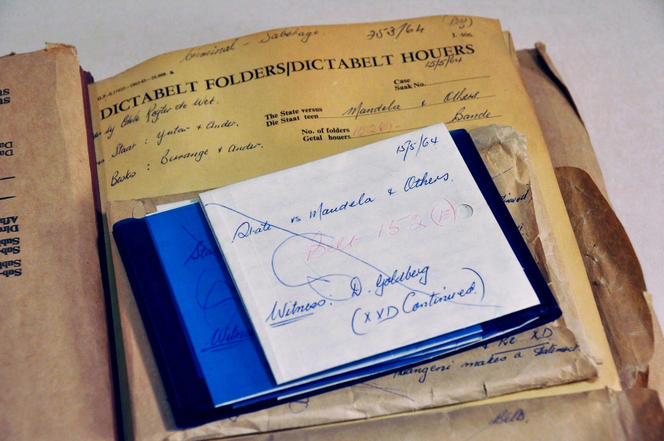

“The difficulty comes from the recording medium, called Dictabelt, used at the time,” explains Henri Chamoux, an engineer at the ENS in Lyon who was in charge of the digitization project for the LARHRA. Developed in 1947 by the Dictaphone company, it is a soft vinyl cylinder that the operator places in a recording device. It rotates in the machine and the sound is engraved on it in the form of a groove, somewhat like early Edison phonographs. Since the vinyl is flexible, the cylinder can then be flattened and placed in an envelope for easy storage.

“This technology was used until the late 1970s, for example to record John F. Kennedy's telephone conversations. The reason why it was preferred to tape recorders, which already existed, during the Rivonia Trial in 1963 could be that on a Dictabelt, the sound leaves a visible mark, making any editing or deletions impossible.”

The Archeophone to the rescue

Some of the Dictabelts used in the trial had already been digitized. In 2001 the British Library was given access to the seven cylinders containing Nelson Mandela’s deposition and they were digitized using an old retooled Dictabelt player. The machine was placed on a laboratory hotplate to smooth out the creases that had marked the vinyl after decades of lying flat in an envelope. Unfortunately, perhaps as a result of this process, two of the cylinders were severely and irrevocably scratched.

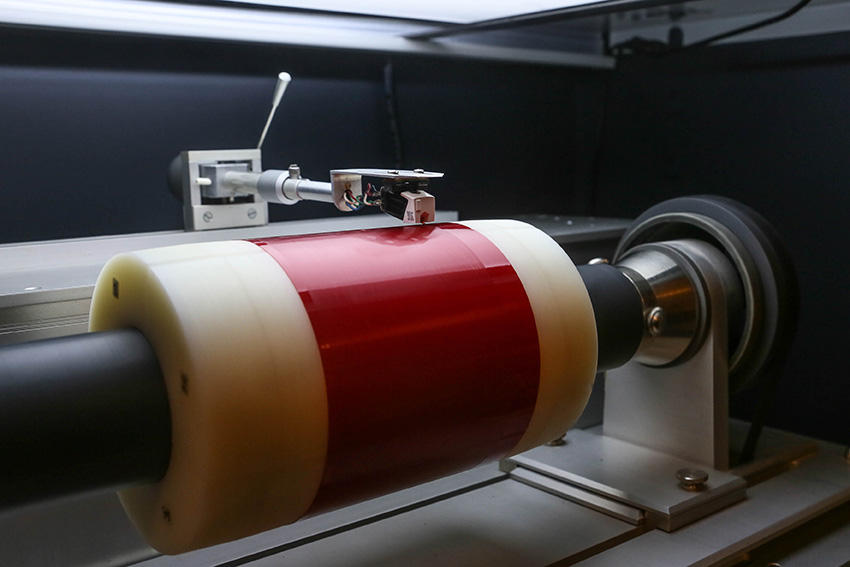

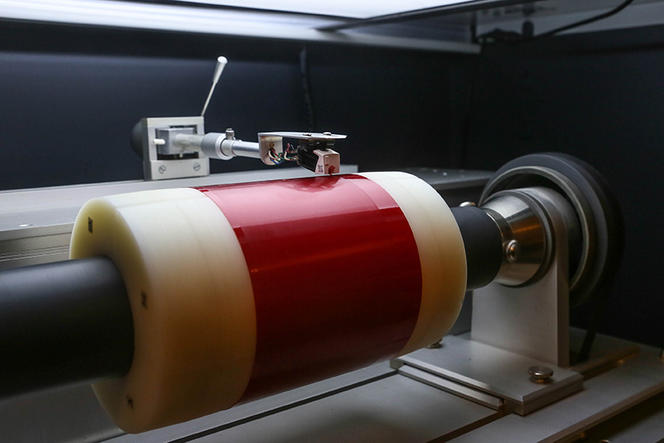

In order to play back all the cylinders without damaging them, another system was needed. The one developed by Chamoux, who completed a PhD on the subject and digitized thousands of recordings from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, seemed to be the perfect choice. “My invention comprises two main parts: a universal cylinder player, which I have named 'Archeophone,' and a special mandrel for Dictabelts,” the engineer explains. “I invented the Archeophone in 1999 to pursue my passion for old records and cylinders. The problem with those is that there are many different models, with different diameters and rotation speeds. Several phonographs are necessary to play them but they also damage them. This gave me the idea of a universal player adaptable to all cylinders.

“About 20 Archeophones have been acquired by institutions like the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the American Library of Congress, to digitize their cylinder collections. As for the mandrel, it is is a cylinder with an adjustable diameter. All it takes is sliding the Dictabelt over it and then enlarging the diameter, which holds the vinyl in place as it rotates and smoothes out any creases. There’s no need for heating, and thus no risk of damage.”

A UNESCO Memory of the World archive

The South African government transferred the Rivonia Trial recordings to the INA in October 2014, and they were digitized by a LARHRA laboratory at the ENS in Montrouge, near Paris. The 591 Dictabelts arrived in eight large albums, whose pages yellowed with age included a sheet for each cylinder giving the names of the speakers and the timing of the content. “It was a moving experience,” Chamoux recalls. “The trial, which ran from October 1963 to June 1964, is a landmark in the history of the black South Africans' fight for freedom. I was the first to listen to all 230 hours of the recordings, which were inscribed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in December 2006.”

Nelson Mandela, the most famous of the defendants, first opted for non-violent resistance against apartheid through the African National Congress (ANC), before converting to armed struggle in 1961. Arrested in 1962, he was initially sentenced to five years in prison for leaving the country illegally. The other defendants were arrested in July 1963 at a farm in the Rivonia region—hence the name of the trial. All were accused of sabotage, destruction of property and violation of the ban on communism, and risked the death penalty.

“A platform for freedom”

“During the 15 months of the digitization project, I lived with their voices: the voices of the defendants and their lawyers, the deep, invariably calm voice of the judge Quartus de Wet, that of the prosecutor, Percy Yutar, who ended every question with a very theatrical upward inflection,2 and those of the minor witnesses, many of whom seemed terrified…," Chamoux recounts. "I was touched by the defendants’ mutual support and by Mandela’s famous final statement (which can be heard here): ‘I have dedicated my life to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal for which I hope to live and to see realized. But my lord, if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.’ These exceptional men turned the trial into a platform for freedom.”

In order to give this chapter of history the best possible audio quality, Chamoux worked for approximately two hours on each Dictabelt, even though a single cylinder holds less than 30 minutes of sound. “Occasionally, the stylus would repeatedly jump at the same spot in the groove, making it impossible to hear the next word. More often still, the speaker’s voice would disappear in places, due not to jumping but to the condition of the groove. I therefore had to turn the cylinder around and digitize it backwards. The stylus would stop jumping, and the words became audible—but backwards! I used audio processing software to invert the content and paste it into the digital recording.”3

A process now available to researchers

When this Herculean task was completed, the digital recordings were sent to the INA for final noise reduction treatment. The purpose here was not to get rid of the incidental sounds of the trial (the banging of folding seats, the observers’ reactions, microphone noise…), which are heard throughout the recordings and help bring them to life, but rather to eliminate the pops and clicks caused by the Dictabelts themselves—a problem well-known to vinyl LP collectors.

As a result, 52 years after the end of the trial, and 26 years after Mandela’s release and the end of apartheid, these historic recordings were returned to South Africa in digital form. The INA also has a copy, which it will soon make available to researchers, students and teachers through its INA-THEQUE resource centers. In addition, plans to share this technology with South Africa in the coming years will enable the country’s archivists to digitize the tens of thousands of Dictabelts in their possession, including recordings of other, less famous trials which are nonetheless representative of the period.

Meanwhile, in the Montrouge laboratory, the voice of Nelson Mandela has been replaced by the sound of old songs, skits and concerts in French and Flemish. The Flemish Institute for Archiving (VIAA) has entrusted the LARHRA with more than 400 cylinders from Belgian museums, municipal archives and universities. If it is not digitized soon, the content of these fragile wax cylinders, some of which are already too damaged to play, could be lost forever. A job made to order for the audio archeologist Chamoux and his ingenious Archeophone.

To find out more:

Henri Chamoux’s website devoted to his invention the Archeophone, with more photos and videos, including one on the history of Dictabelts (French).

The INA-THEQUE website (French).

- 1. CNRS /Universités Lumière-Lyon 2/ Jean Moulin-Lyon 3 / Grenoble Alpes/ ENS de Lyon.

- 2. Statement by Nelson Mandela (April 20, 1964): final introductory remarks by defense lawyer Bram Fisher; a few words by Nelson Mandela, interrupted by attorney general Percy Yutar; response of judge Quartus de Wet; beginning of Mandela’s deposition from the dock.

- 3. 15-second fragment of the hearing, before and after recuperation of an inaudible passage.

Explore more

Author

Holding both an engineering degree and an MA in art history, Philippe Nessmann has three passions: science, history and writing. As a journalist, he regularly contributes to Science et Vie Junior, Ciel et Espace, le journal du CEA... He is also a published author of over fourty books aimed at a young audience, including historical novels (coll. Découvreurs du...