You are here

A Detour through the Uncanny Valley

The notion of the Uncanny Valley, invented in the 1970s by the roboticist Masahiro Mori, refers to the fact that when an object reaches a certain degree of anthropomorphic resemblance to humans, a feeling of anxiety or unease appears. This is true whether the object is an android, a prosthesis, or a puppet. It can be illustrated by a graph in which the Y-axis represents familiarity (or sympathy), and the X-axis, the degree of anthropomorphism. The term "valley" corresponds to a sharp drop in popularity when objects become more resembling, followed by a steep rise as the level of perfection in imitation increases. But where does this phenomenon come from?

Man-robot: an ambiguous relationship

Coined by the science fiction author Karel Capek and based on the Czech word for "chore"—it also means "slave" in Slavic languages, "to work" in Russian, and "worker" in Slovak or Polish—the term "robot" has always designated a machine with a human appearance, created to stand in for humans in difficult tasks. However, the problem arose quite early on as to our ambiguous relationship with a creature that more or less resembles us.

Whether it takes the form of a drone, avatar, Japanese sex doll, or a real autonomous robot with cognitive capacities resembling our own—and which can also kill us—this "friend-slave" raises profound anthropological questions. These issues are the subject of the "Persona" exhibition at the musée du quai Branly in Paris, which explores the "living" from a mental, linguistic, cognitive, and religious point of view, from primitive art to robotics. It shows how different cultures grant the status of living being to all sorts of physical objects, and not just to those that resemble us. It also demonstrates that the unease felt when faced with a zombie or living dead can fall within Mori's notion, which places the corpse at the very bottom of its Uncanny Valley.

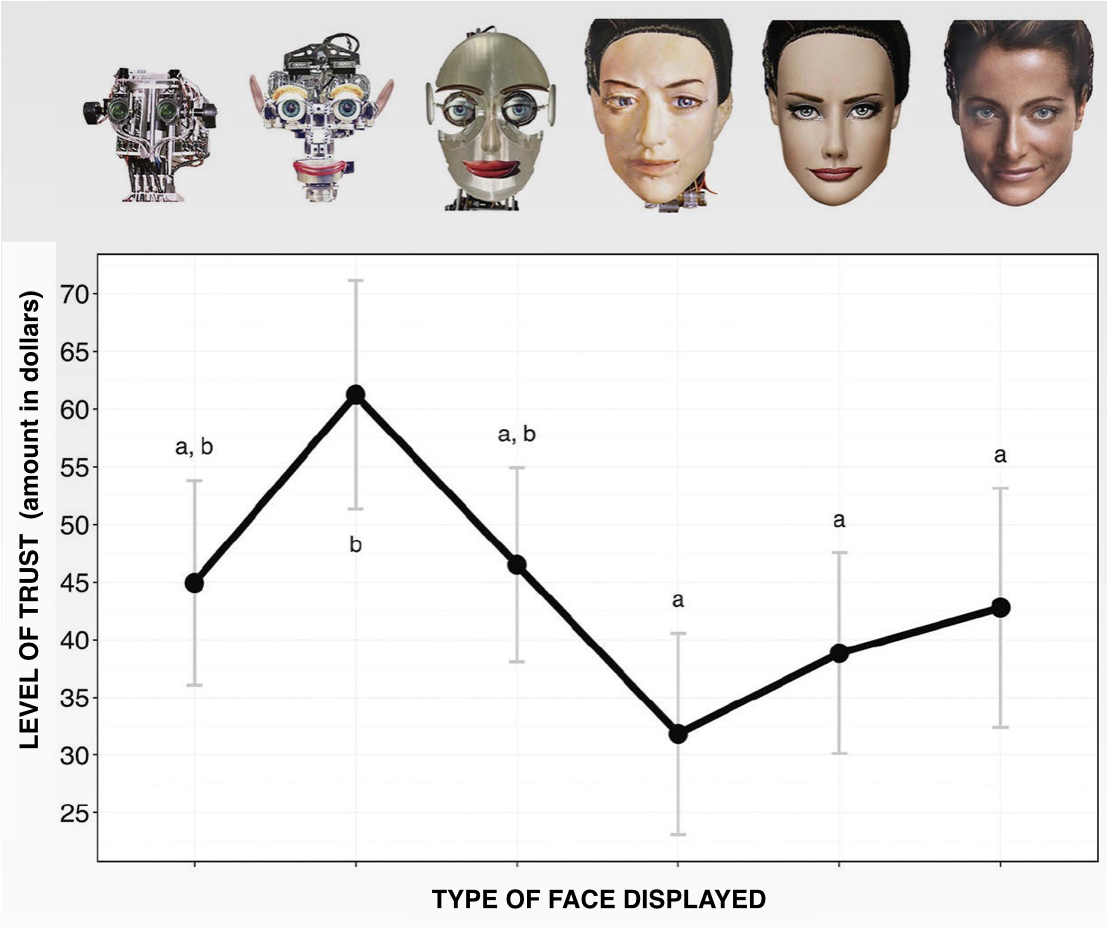

Yet one may wonder to what extent this "Uncanny Valley" actually exists. In any case, recent experiments in psychology1 seem to support this reality. Among these, one in particular required subjects to bet money with virtual gaming partners whose faces looked more or less human—on the premise that the more a player trusts a game partner, the more they will bet. The betting curve related to the degree of human resemblance of these partners faithfully reproduces Mori's Uncanny Valley: the "not entirely but almost human faces" are in fact those that inspired the least amount of confidence.

A rejection due to uncertainty

For Frédérique de Vignemont, a philosopher in cognitive science at the Institut Jean Nicod,2 "one hypothesis is that the brain does not like uncertainty at all. This robot, which resembles you vaguely but not entirely, sends contradictory information as you see it both as a human and a non-human. We know that the brain does not like cognitive dissonance, and is desperate to find a solution when faced with contradictory information." The unease thus apparently stems from the brain's interpretation: better flee what I cannot categorize than make an error.

Another explanation is apparently more fundamentally linked to our evolutionary adaptation. "We know from behavioral psychology that children under one year of age are able to differentiate between a biological movement made by an animal or a human, and one that is purely mechanical," adds the researcher. “We therefore apparently possess an innate detection system that is biological in nature. Biases emerge as early as 3-4 months of age with regard to skin color, belonging, and language. Because of the way we are built, we need to belong to one group, and we reject the other. Given that from a very young age, I can make the distinction between that which will protect me and that which will potentially be a danger, when faced with uncertainty regarding a robot, I tend to reject it and to 'place' it outside of my group. This behavior appears very early on from a developmental standpoint."

Jean-Louis Vercher, of the Institut des sciences du mouvement,3 studies bio-inspired robotics in biomimetic prosthetics. He explains how roboticists henceforth take into account the Uncanny Valley phenomenon: "We realized that a prosthesis that resembled a robot's hand was much better accepted by patients and those around them than a realistic hand, since it was clearly identified as a prosthesis, rather than a defective hand." At the request of users, the engineers have begun to adopt a plainly robotic design over the last two or three years: the prosthetic hand is made of visible metal, and resembles a pair of articulated pliers with two or three fingers, or even a cyborg hand.

In fact, fewer and fewer amputees choose the hand made of rubber that mimics skin, with its wrinkles, veins, and nails... which firmly fix it in the Uncanny Valley. Engineers nevertheless hope to achieve a sufficient level of realism in order to reach the other slope of the valley, where anthropomorphism becomes acceptable again. For the time being, the tendency is to show one's prosthesis in all its artificiality. Some even go so far as to assert the erotic dimension of mechanics, such as Viktoria Modesta, an amputee and artist who does not hesitate to stage her prosthetic leg.

Empathy through movement

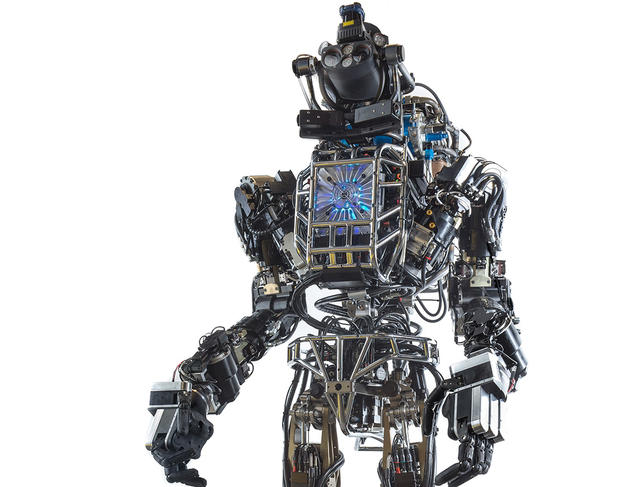

Certain robots resemble humans not through their static appearance but in how they move around. These robots, which were built to help improve our understanding of locomotive interactions, can involuntary produce a striking visual effect. This is the case with the humanoid Atlas, which is programed to generate small bio-inspired movements. Its software reproduces the fine retroactive loops found in the motor nervous system of animals. It avoids obstacles and can regain its balance as a living being would, even if it does not resemble one. "If you kick the robot, you can see that it has difficulty in recovering, which triggers emotion. We feel empathy for something that is both familiar and distant," points out Vercher. In this case, it is movement that establishes this distortion, which can be disturbing, between the impression of observing a living gesture and the fact that it is produced by a machine made of metal.

Incidentally, the psychologist Gunnar Johansson has shown that the brain is able to recognize whether a movement was biological or not, based on a few visual dynamic clues. This capacity is linked to the activity of a specific area of the temporal cortex. The procedure is the same as in cinema animation: a few white tabs are attached to a walking human body; these tabs are then filmed, and the video of a few white dots in movement is played against a black background. Twelve dots are enough to identify whether it is a living being, and to even determine its gender, weight, ease of movement, etc.—so much information that can be inferred simply from how it moves.

The same type of phenomenon occurs when we watch Atlas: our brain connects the dots and identifies it as living. This makes the robot more familiar, but it can also take it to the edge of the Uncanny Valley... The assumptions of science fiction actually make up a cultural substrate that feeds the imagination of roboticists and users alike. Knowing whether we are addressing a heap of scrap iron or a person is THE robotics question since the Turing test: to know whether this machine thinks or dreams of electric sheep...

The concept of the Uncanny Valley dates back to the early days of robotics, and remains the subject of much debate. Its return to fashion is especially due to the Japanese infatuation for androids and sex dolls, as well as the love dolls they marry, and for whom they even plan funeral services. In Europe and the US, there is a preference for producing robots that look like robots, with the notable exception of machines that—like Nao—have a pedagogical purpose, or of animated cuddle toys to keep the elderly company. Android appearance or not, the "Persona" exhibition provides a universal perspective on the human brain's eternal temptation to attribute intentionality to inanimate objects—enough to reassure oneself when talking to the coffee maker while half asleep, or encouraging a slow computer with a few friendly taps.

Explore more

Author

Lydia Ben Ytzhak is an independent scientific journalist. Among other assignments, she produces documentaries, scientific columns, and interviews for France Culture, a French radio station.