You are here

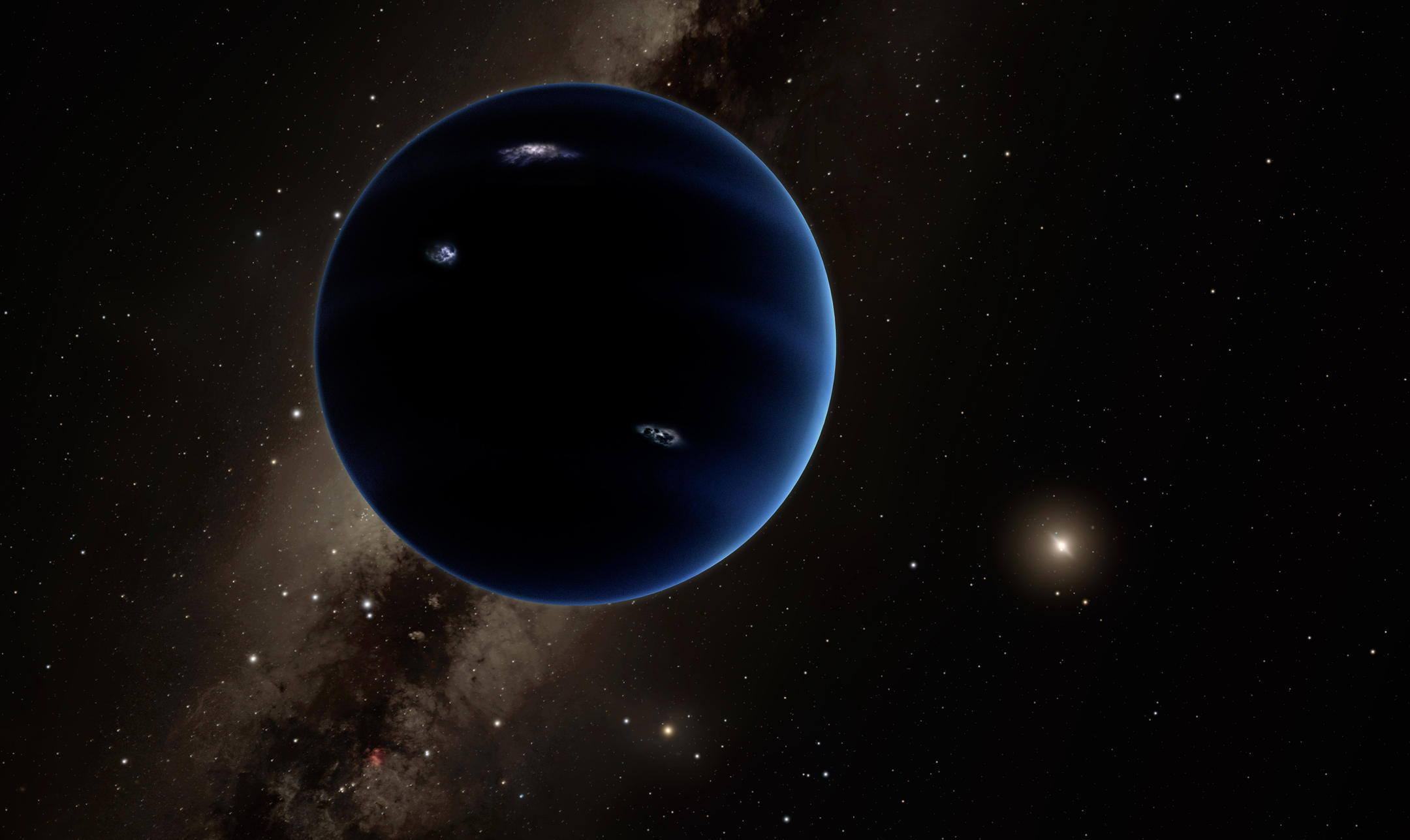

The Ninth Planet

"In space no one can hear you scream." Thrill seekers will recognize the quote, as will everyone else. Yet recent news is making noise—the discovery of a new planet. And not just anywhere, but right on our doorstep, in our Solar System. The scientific community is bubbling with excitement, enthusiasts are in a frenzy, and the public is abuzz, contemplating in awe a sky that continues to yield, little by little, its unfathomable mysteries...

A second... ninth planet?

Let's not get carried away. To take things from the start, the term "discovery" is somewhat of an exaggeration, since nobody has observed this planet. For now and perhaps for a long time to come, it is only a conjecture arising from calculations by a team of US researchers from the California Institute of Technology (Caltech), whose article has just been published in The Astronomical Journal. For this is what Science is all about, it doesn't provide certainties every other day, but generates hypotheses, which it then compares, analyzes, verifies, and ultimately validates or rejects. Besides, it is not the first time a ninth planet has supposedly been found! In 1930, Pluto made a grand entrance into our Solar System—only to be relegated to the rank of "dwarf" in 2006, by a resolution from the International Astronomic Union. So before anxiously scrutinizing the skies, it may be wise to glance in the rear-view mirror...

Naming planets after gods, an old habit

The eye, precisely, is astronomers' first instrument. Since the distant past, it has enabled them to observe five of the planets in the Solar System: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. Of course, it has not always been simple: while the large and very bright Jupiter is easily observable, seeing Mercury with the naked eye is a different story. Incidentally, throughout this "distant past," naming planets after gods became a habit quite early on. It goes without saying that the Mesopotamians were not referring to "Jupiter," but the "star of Marduk," the tutelary deity of Babylon; that for them Venus was the "Star of Ishtar," their goddess of love, and so on for Mars ("Nergal"), Saturn ("Ninib"), and Mercury ("Nabu," which is pronounced like "Naboo" in Star Wars...for those who are still following!). The same goes for the Greeks, with in the same order, Zeus, Aphrodite, Ares, Kronos, and Hermes. Not to mention the Romans, who left their names as heritage, a legacy that we dull monotheists lacking in inspiration have only been able to imitate with the discovery of new planets.

Only seven planets at the end of the 18th century

Uranus was the first newcomer. The star was discovered in 1781 by William Herschel, who initially thought he was observing a comet. This finding, which came thirteen centuries after the fall of the Roman Empire, did not go unnoticed for the discovery of a new planet is not frequent, to say the least! Instruments, such as astronomical glasses and later the telescope, also helped. Galileo's pioneering role is well worth mentioning, especially in this year of 2016, which marks the 400th anniversary of his first trial. At the end of the Enlightenment, the Solar System counted seven planets including ours, and saw its dimensions extended with the orbit of Uranus, which is twice that of Saturn.

Incidently, while the discovery of Uranus is often described as an "accident" since Herschel was not looking for it at the time of his observation, it should not be seen as a surreptitious finding. For a number of years, the astronomer had indeed been engaged in a vast undertaking of inventorying celestial objects. In short, this fortuity nonetheless stemmed from an inexhaustible intellectual curiosity. This is Science as well.

According to calculations, Uranus shouldn't be there!

And Science is also more than that, for the developments it underwent—from, say, Newton to Laplace—offered capacities of prediction that, 65 years on, led to the discovery of a new planet in the Solar System, Neptune. For the first time, this finding preceded observation itself, which calls for a few explanations. In his Treatise on Celestial Mechanics, Laplace provided the mathematical expression of the disturbance exerted by planets due to their gravitational attraction. Learned calculations, performed by the "Bureau des longitudes" established by the National Convention, later made it possible to determine their position over time. From the early 1820s, one of the members of the Bureau, Alexis Bouvard, dedicated himself to the tables of Jupiter, Saturn, and Uranus. For the first two, all was for the best in the best of worlds. Yet it all went wrong with the third: Uranus was simply not in the right place! But you try to tell a giant planet that it’s not in line with the calculations of a French astronomer...

When a wise man points at the moon

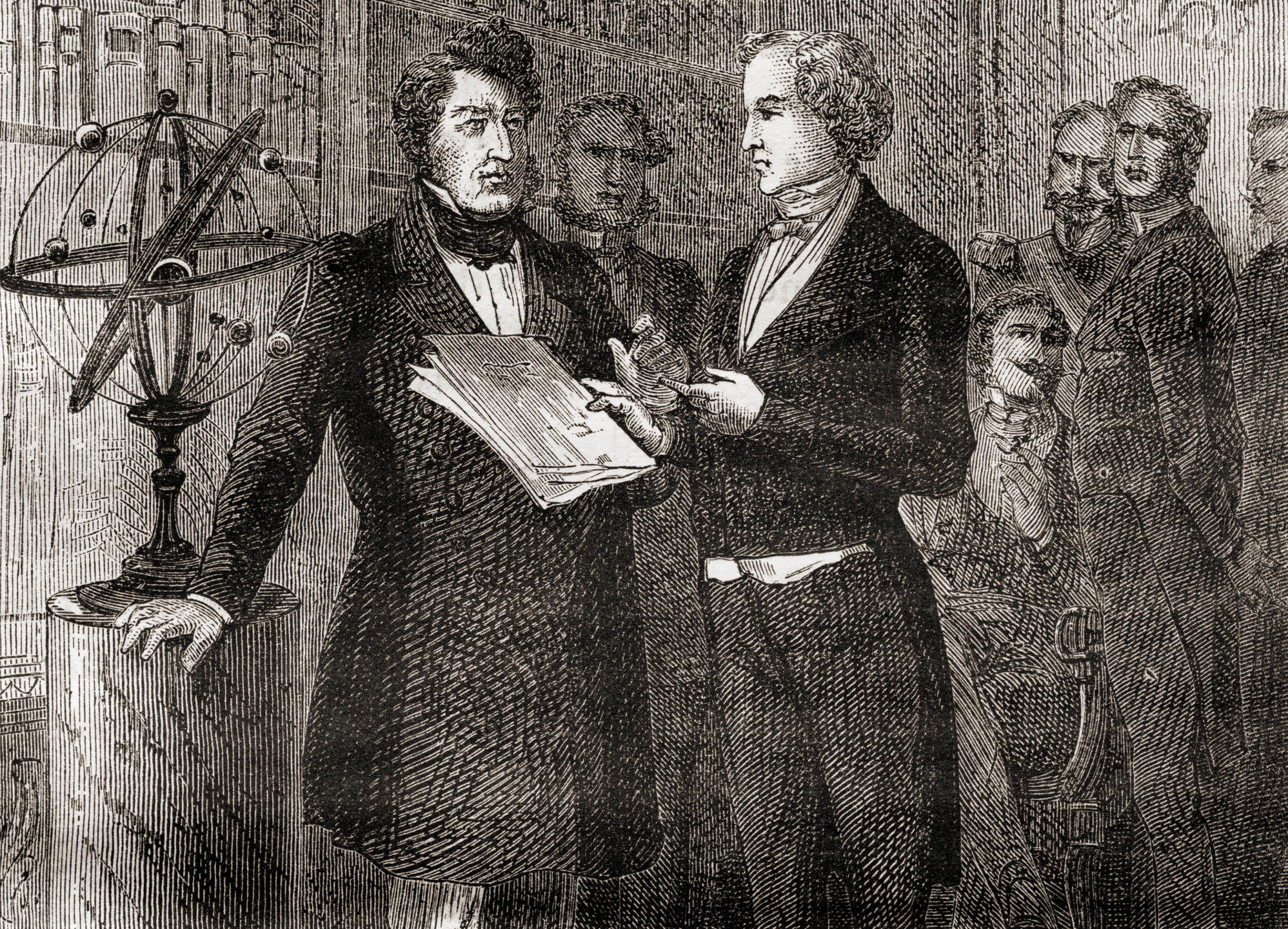

"If the facts don't fit the theory, change the facts," advised Einstein a century later. This is exactly what scientists did. Could the existence of an unknown body that disturbed the movement of Uranus be the new fact that would confirm the theory? A young astronomer named Urbain Le Verrier demonstrated it in 1846. In a few months, he succeeded in calculating the mass and the orbit of this "troubling" planet, which was observed shortly afterwards in Berlin. The then director of the Paris Observatory, François Arago, paid homage to the discoverer at the Academy of Science: "Le Verrier has observed the new star without needing to cast a single glance toward the sky; he saw it with the point of his pen." We already knew that the pen is stronger than the sword, and now it proves better than the eye and telescope combined.

Before the existence of this second "ninth planet" is confirmed, the old adage is worth reconsidering: when a wise man points to the Moon, it is not necessarily foolish to also look at his finger...

The analysis, views and opinions expressed in this section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policies of the CNRS.