You are here

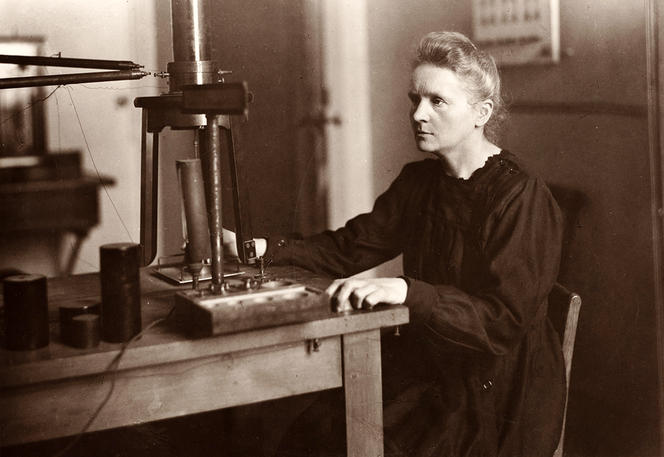

Marie Curie, Pioneer and Double Nobel Prize Winner

The plethora of publications, tributes and events devoted to her over the years, both in France and around the world, suggest that there is nothing new to say or write about Marie Curie. And yet her life, her work and her exceptional human and scientific qualities always elicit the same admiration: it is quite simply impossible not to be dazzled by this figure from our contemporary history. as the celebration of the 150th anniversary of her birth will no doubt confirm.

From Warsaw to Paris

Maria Salomea Skłodowska, the youngest of five siblings, was born on 7 November 1867 in Warsaw, in a Kingdom of Poland under the yoke of Russia. Both her own testimony and surviving records provide an accurate picture of her early years: she was a little girl whose precocious abilities were quickly spotted by her family and teachers, an adolescent struck by a series of tragedies—she lost a sister to typhus, and her mother to tuberculosis—and a young woman concerned by the situation in her country and determined to escape her condition through hard work and study. It almost reads like the introduction to a novel, ripe with clichés, and yet this is roughly what the first years of her existence were like.

The rest of her life was to be spent in France, in Paris, where she came in September 1891 to continue her science studies freely. And what studies they were: Marie (she had Frenchified her name) ranked first in her science and physics degree in 1893. The same year, she met Pierre Curie, a physicist who shared her passion for research. While she had previously had no qualms in turning down all her suitors, who, captivated by her personality and charm, might have distracted her from her work, she married him on 26 July 1895. Their modest wedding ceremony took place in the strictest privacy. As Pierre and Marie Curie, they were destined to become two of the brightest stars in the scientific firmament.

Consecration and tragedy

Although the entire career of this legendary couple cannot be summed up here, one point at least needs to be clarified: despite many (male) scientists' scepticism, research into radioactivity was Marie's idea. Pierre dropped his own work into magnetism and joined his wife in a field that quickly appeared to him to be more challenging and promising. Working in destitute conditions that have frequently been related, they were to write one of the finest chapters in the history of science, sharing in 1903 the Nobel Prize in Physics with Henri Becquerel "in recognition of the extraordinary services they have rendered by their joint researches on the radiation phenomena discovered by professor Henri Becquerel."

However, consecration was to be followed by tragedy: on 19 April 1906, Pierre was accidentally killed in Paris, run over by a horse-drawn carriage as he crossed the Rue Dauphine after attending a meeting with the famous French physicist Jean Perrin. Marie's grief was only matched by her determination to continue their shared work: not only did she succeed Pierre in his teaching at the Sorbonne—on 5 November 1906, she symbolically took up his course from the exact sentence where he had left off several months earlier—but she also discovered two new elements, radium and polonium, which earned her a second Nobel Prize, this time in chemistry, in 1911. The first woman to teach in higher education in France, Marie Curie is first and foremost the only scientist ever to have been awarded two Nobel Prizes in two different disciplines.

Promoting 'pure science'

As if to give the lie to the stereotype of the absent-minded scientist, she also turned out to be an outstanding organizer, as borne out by her creation of the Radium Institute in 1912, and by the role she played as director of the Red Cross Radiology Service during the First World War. Several years later she looked back at this experience, in a fascinating book entitled Radiology in War, in which she revealed some of the commitments that meant the most to her, such as feminism: "It is a pleasure for me to recall that the first mobile radiography units set up at my initiative were donated by the Union des Femmes de France (Union of French Women) and equipped at their expense."

Subsequently, Marie Curie spared no effort when it came to organizing and promoting research. Aware of the difficult conditions in which French scientists worked—she often recalled that the laboratory she had shared with Pierre was "a wooden shed with a bituminous floor and a glass roof, which did not keep the rain out and without any interior arrangements"—she joined the campaign initiated by Jean Perrin between the two world wars. It was then, perhaps, that she most happily gave up her down-to-earth writing style for a more lyrical one: "The repercussions of creative thinking are endless. Its scope reaches beyond all known horizons. Every civilized community has a bounden duty to look after the domain of pure science, which is a crucible for ideas and discoveries, to protect and encourage those who work in it, and provide them with all necessary support. Only then can a nation grow and pursue harmonious development towards a distant ideal." In this area as in so many others, Marie Curie, who has lain at rest with Pierre in the Panthéon in Paris since 1995, still has much to teach us.

The analysis, views and opinions expressed in this section are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policies of the CNRS.