You are here

Scientists for the French Republic

In the midst of our 80th anniversary celebrations, it is worth noting that the launch of the CNRS, Europe’s largest public research organisation, went virtually unnoticed. Indeed, the context was hardly celebratory when president Albert Lebrun signed its founding decree on October 19, 1939. At a time when France had just entered the war against the Third Reich and was faced with the fall of Poland, the initiative did not seem to amount to much by itself. In fact, it was said to be dictated by the circumstances: according to the decree, the key mission of the CNRS was to ensure the country’s “scientific mobilisation”. Yet this explanation overlooks an essential fact. The CNRS was indeed born without fanfare into a world at war, but it was nonetheless the result of a long genesis, which is worthy of our attention.

The origins of our institution can be traced all the way back to the Franco-Prussian War of 1870-71. After France’s defeat by the Prussian army under Bismarck and Kaiser Wilhelm I, its scientists agreed that the country had not been beaten on the battlefields but in the laboratories. For Louis Pasteur there was no doubt whatsoever: the “motherland’s misfortunes” were due to “the weakness of scientific organisation”.1 In the early days of the Third Republic, this realisation spawned a number of reforms in higher education and budget increases for universities and institutions like the Collège de France, the national museum of natural history (MNHN), etc. The scientists themselves also proposed various initiatives, one of the most famous of which was the founding of the Institut Pasteur in 1888.

Still, France struggled to organise scientific research, despite its efforts: in 1901, a fund for scientific research was created, but its budget was scarce, to say the least.2 Although he was a professor of medicine, Edmé Bourgoin, a member of Parliament, warned his fellow legislators: “Those who want to engage in research should not ask the government for hand-outs…” Even after heeding their nation’s call to duty during the Great War, French scientists in 1918 returned to destitution. Although the term — “misère” in French — may sound too harsh, it features time and again in the archives, and even in the writings of Maurice Barrès: “Our laboratories are totally destitute,” the nationalist author lamented in a book published in 1925,3 denouncing the situation as “unworthy of France, unworthy of science.”

Science in need of organisation

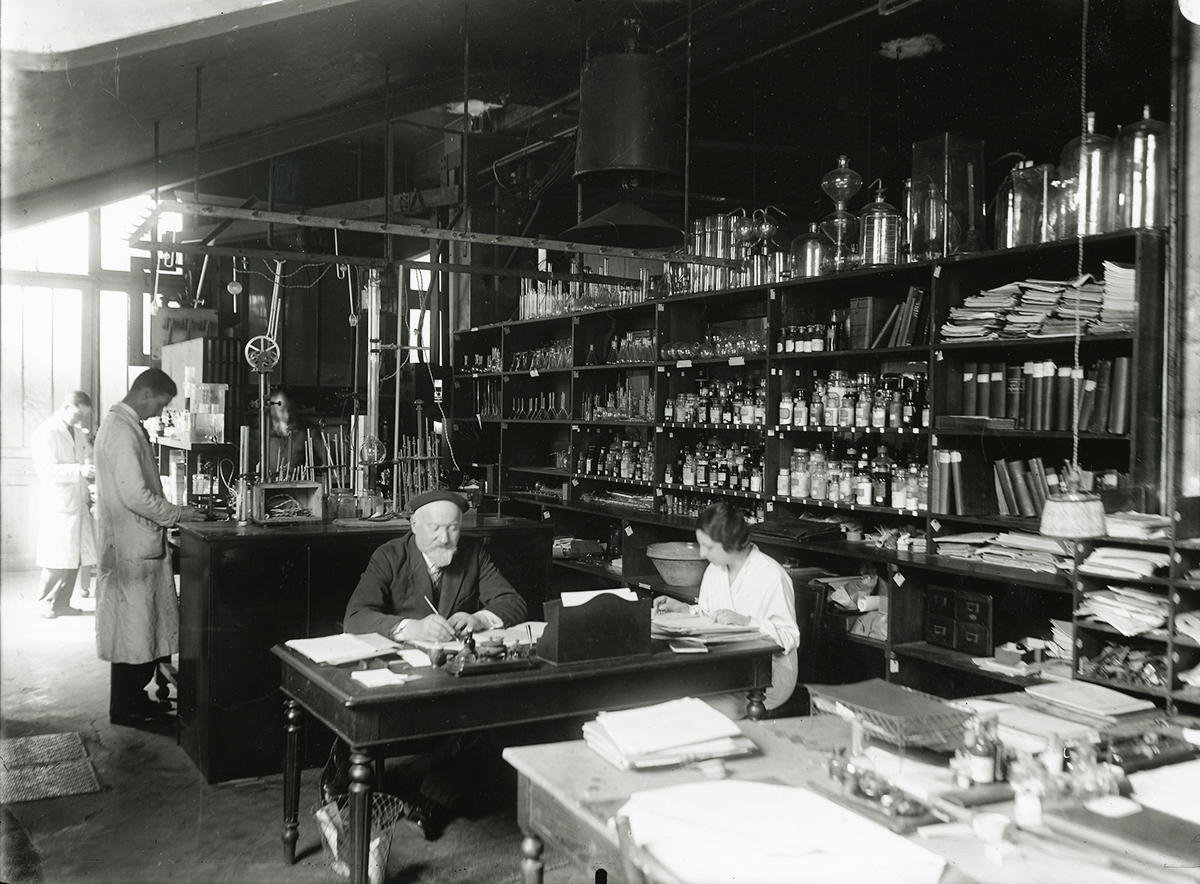

The following year, the physicist Jean Perrin was awarded the Nobel Prize “for his work on the discontinuous structure of matter”. In 1927, with the backing of a foundation created by the banker Edmond de Rothschild, he opened a state-of-the-art laboratory: the Institute of Physico-Chemical Biology (IBPC). Within its walls researchers set to work, with the sole mission of plumbing what the illustrious scientist called “Nature’s most deeply hidden secrets”. In addition, by bringing together physicists, chemists and biologists, the IBPC was intended to unite these disciplines and encourage their cross-fertilisation. It was an “interdisciplinary” organisation before the term was even coined!

The concept was a resounding success, and soon raised the question of whether it should be extended to the rest of the country. Jean Perrin made this a personal mission over the following decade. In 1930, under Prime Minister Édouard Herriot’s government, he obtained the creation of a Caisse Nationale des Sciences (CNS) — renamed Caisse Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique, or CNRS, in 1935. In 1933, he convinced the Daladier government to establish a Conseil Supérieur de la Recherche in charge of sketching the outlines of the country’s nascent scientific policy.

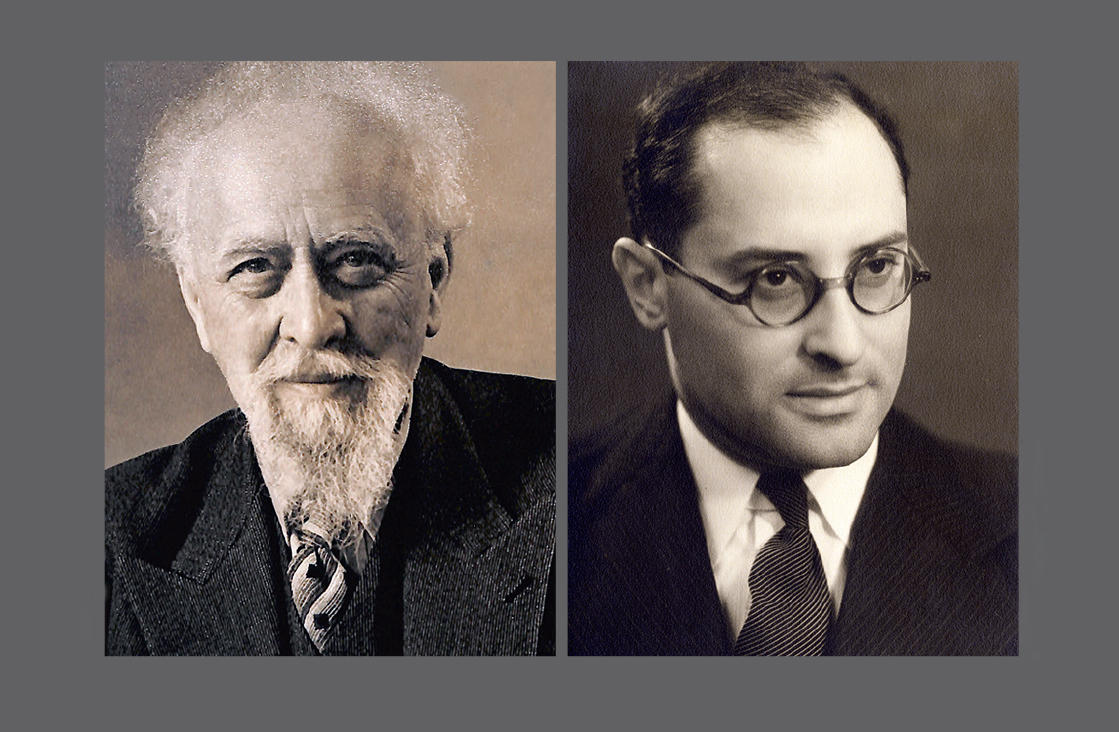

1936 was a milestone. France’s left-wing Popular Front parties won the legislative elections. Prime Minister Léon Blum appointed the 32-year-old legislator Jean Zay as Minister of National Education. His office was to include an Under-Secretary of State for Scientific Research — a first in French history! Irène Joliot-Curie was given the position, but soon resigned. Jean Perrin replaced her in September of that year: “This illustrious seventy-something Under-Secretary of State immediately showed the ardour of a young man, the enthusiasm of a beginner, not for the honours, but for the means of action that they provided,” Zay noted in his memoirs.4

The next few months saw rapid progress. The ministry opened a Central Research Department and the CNRS’s budgets were considerably increased, enabling the construction of several institutes — the IAP,5 the IRHT6… A smooth process took shape: the Council deliberated and put forward proposals, the Department made decisions and implemented them, the Fund provided financing… Already, there was talk of merging them all into a “single centre”, but the fall of the Blum government and international tensions delayed its creation: the National Centre for Scientific Research would not see the light of day until 1939, a posthumous child of the Popular Front. In short, while the war gave it a boost, it is only the tip of the iceberg in the genesis of an organisation meant to “initiate, coordinate and encourage research in pure and applied science” across the country.

Mobilised, occupied, liberated

But war was well and truly raging, and from May 1940, the CNRS bore the brunt of the fall of France and the Occupation — facing shortages, isolation from international research, the looting of its equipment by Nazi Germany… In addition to these hardships, the new exclusion measures took a heavy toll on its personnel: the anti-Jewish laws deprived the laboratories of many researchers and technicians, who suddenly found their livelihoods, and very lives, under threat. Without entering into an inventory of personal tragedies, the fate of the Centre’s two founders is eloquent enough: Jean Perrin died in exile in New York on April 17, 1942, while Jean Zay was imprisoned by the “French government” based in Vichy. He remained captive until June 20, 1944, only to be cowardly killed by the pro-Nazi militia. Today the two men are reunited in the prestigious Panthéon mausoleum, where Perrin was laid to rest in 1948, joined by Zay in 2015. The CNRS can thus claim to be the only research organisation whose founding fathers are interred in the nation’s shrine.

After the Liberation, the Centre was headed by figures who were eager to break away from the authoritarian practices of the Vichy government. From 1944 to 1946, Frédéric Joliot-Curie, followed by Georges Teissier until 1950, strove to involve scientists in defining the orientations of research and championed the creation of a “Parliament of Science”. Perhaps the chemist Henri Moureu, who participated in this revival, put it best: “So you want to turn us into a Republic!”7 It was indeed a sort of “scientific republic” that was emerging, coming to fruition in 1945 with the creation of the “National Committee for Scientific Research” (CoNRS), an institution destined to a long and illustrious future.

After the immediate post-war years, the CNRS entered a period of steady growth. It opened units in the Paris region and in an increasing number of locations throughout France: Grenoble, Marseille, Strasbourg, Toulouse… It also inaugurated its first campuses: after the Meudon-Bellevue site (Paris), which the CNRS took over from the Office National des Recherches Scientifiques et Industrielles et des Inventions8 in 1939, the first one opened in Gif-sur-Yvette (near Paris) in 1946. One of its main missions was to promote the study of genetics, a field that French universities were slow to embrace.

Speaking of universities, which had gone their own separate way, they underwent a far-reaching transformation in those years, integrating doctoral studies in 1954, investing in laboratories, and playing a central role in the symposium on education and scientific research held in Caen in 1956 under the patronage of the French politician and statesman Pierre Mendès France. Long criticised for their deficiencies in terms of research, they became a scientific player in their own right. The next step was to coordinate the efforts of this grand old institution — by then undergoing a makeover — with that of the young and dynamic CNRS. This would become one of the key challenges of the 1960s…

- 1. Quelques Réflexions sur la Science en France, Louis Pasteur, Gauthier-Villars, 1871.

- 2. La Science au Parlement: les débuts d’une politique des recherches scientifiques en France, Michel Pinault, CNRS Éditions, 2006, p. 15.

- 3. Pour la Haute Intelligence Française, Maurice Barrès, Plon, 1925, p. 64.

- 4. Souvenirs et Solitude, Jean Zay, Belin, 2011, p. 312.

- 5. Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris (CNRS / Sorbonne Université).

- 6. Institut de Recherche et d’Histoire des Textes (CNRS).

- 7. Minutes of the meeting of the CNRS executive committees, 18 September 1944, Archives Nationales.

- 8. Rêves de Savants. Étonnantes Inventions de l’Entre-deux-guerres, Denis Guthleben, Armand Colin, 2011.