You are here

When beauty overshadows scientific genius

On 10th June, 1941, with her friend the composer and pianist George Antheil, Hedy Lamarr filed a patent entitled ‘Secret Communications System’ with the United States Patent Office. What exactly was their invention?

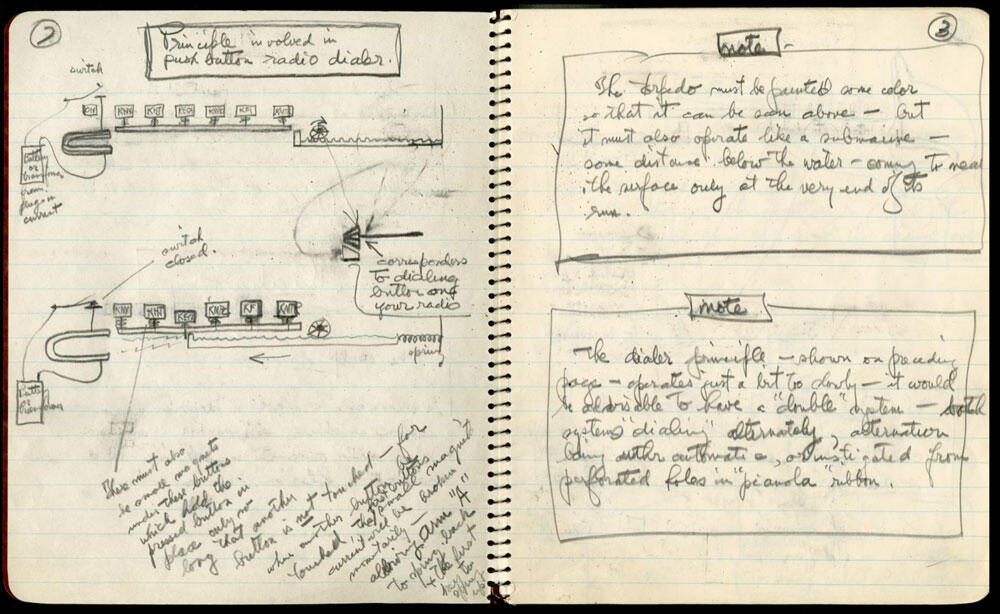

Olga Paris-Romaskevich1: The patent was filed in the middle of the Second World War, when there was a vital need to protect communications, for example on board a ship attacking a submarine. The enemy could intercept the signal between the ship’s radio guidance transmitter and a torpedo equipped with a radio receiver. In their patent, Antheil and Lamarr proposed the use of what is now called ‘frequency hopping spread spectrum’. During transmission, the signal jumps from one radio frequency to another, following a random and nonperiodic order known in advance by the transmitter and receiver, like a secret code. This made it possible to transmit instructions without the enemy being able to intercept or jam the signal.

Isabelle Vauglin2: What’s fascinating is that their solution is as poetic as it is ingenious: the two inventors took their inspiration from the workings of player pianos. In these instruments, the holes of punched cards (like the ones used in early computers) act as controls, determining which keys are to be played. In fact, the order of the frequency change proposed in Lamarr and Antheil’s patent is nothing but a piece of music played on a piano! They also suggested the use of 88 different frequencies, which corresponds to the number of keys on a piano. The patent even mentions the idea of using a player piano-like mechanism to control the frequency change.

Today, frequency hopping spread spectrum is used in many communication technologies, including Bluetooth and GPS. Should Hedy Lamarr be remembered as the pioneer of modern telecommunications?

O. P.-R.: It’s important here to avoid two pitfalls. For one thing, we mustn’t overlook the contribution of Antheil and Lamarr, who had no formal scientific education and nonetheless made a significant contribution to intellectual history. But at the same time, we mustn’t think that they were the first to propose frequency hopping – an idea whose exact history seems difficult to trace. In any case, similar patents had already been filed in the 1920s and 1930s, in particular by a Dutch engineer named Willem Broertjes in 1929. It is likely that Hedy Lamarr became aware of these concepts when she was in Austria and married to Friedrich Mandl, an arms dealer with close ties to the Nazi regime.

I think that Lamarr and Antheil both have a rightful place in the history of science. They exemplify the idea that science belongs to everyone. Hedy Lamarr was not a professional researcher, but she was a citizen committed to fighting fascism and she made a real contribution to the advancement of telecommunications.

I. V.: It’s really remarkable! She was completely self-taught. Her ability to understand, remember and repurpose these concepts is quite impressive. Even though we cannot call her the true pioneer of modern communication, her role in the development of these techniques remains crucial. With the patent that she co-signed in 1941, she clearly made her mark on the history of telecommunications.

Still, she gained no recognition for her patent until nearly half a century later, in 1997, when she received the Electronic Frontier Foundation Pioneer Award as well as the Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award, often termed the ‘Oscar of inventing’. Was she a victim of her image as a screen beauty?

O. P.-R.: Her intelligence was often considered superfluous, that’s for sure! To her first husband, Friedrich Mandl, she was just a pretty plaything. Lamarr escaped from this marriage in 1937. Later, in the United States, the film producer Louis Mayer ‘sold’ her as ‘the most beautiful woman in the world’. The men around her recognised only her beauty, not her intelligence – except for George Antheil! Although they had filed their patent, with the goal of helping the Allied cause, Lamarr was asked to tour the United States, selling kisses to promote the sale of war bonds… Which she did. She relied on her beauty to make a living. But even so, she never stopped dreaming up inventions.

I. V.: That’s right. And she was locked into this straitjacket by everyone. She had genuine scientific curiosity, a thirst to understand how things work. But society only supported her in her acting career, never for her scientific ambitions. It’s true that her father nurtured her interests when she was a child, encouraging her to ask questions and explaining how mechanical things worked, but ultimately her parents never pushed her to pursue studies in this field.

Was she a victim of the Matilda effect, the phenomenon of overlooking women scientists in favour of their male colleagues?

I. V.: In a way, yes. This phenomenon was first conceptualised by the sociologist Robert K. Merton, who had studied the reputations of scientists in relation to their position in their organisations’ hierarchical structure. He noted that project leaders often received recognition disproportionate to their actual contribution. He called this social mechanism the ‘Matthew effect’, in reference to this passage from the Gospel of Matthew: ‘For whoever has, to him shall more be given, and he shall have an abundance; but whoever does not have, even what he has shall be taken away from him’.

Later, (the science historian – Ed’s note) Margaret Rossiter applied the concept to women scientists whose work and discoveries are minimised. She called it the ‘Matilda effect’ in honour of Matilda Joslyn Gage, an activist who fought for the recognition of women. History is full of telling examples: Lise Meitner, who co-discovered nuclear fission with Otto Hahn but was passed over for the Nobel Prize in 1945; Rosalind Franklin, whose photograph revealing the double helix structure of DNA was simply stolen by Watson and Crick, who received the 1962 Nobel Prize without her; or Jocelyn Bell, whose PhD supervisor refused to allow the inclusion in her dissertation of her discovery of the first pulsar, and who received the Nobel Prize in her place in 1974…

O. P.-R.: And sadly, this effect still exists. It continues today at all levels of research.

What actions are each of you taking to improve the situation?

I. V.: To encourage women to take up scientific careers, Femmes & Sciences organises a number of operations, in particular the exhibition ‘La Science taille XX elles’ (in partnership with the CNRS) and ‘Science, a woman’s profession!’, an annual event for women conceived to break down gender stereotypes and show via female role models that all scientific professions are mixed. For the ninth edition, to be held at the École Normale Supérieure de Lyon on 11 March, we have already received 870 participation requests, showing how much this initiative addresses a need.

We also offer a mentorship programme, because women need support and encouragement to take their place in environments that remain very male-oriented. It’s important to convey a message of hope: despite the sexism and patriarchy that persist in scientific circles, women can find allies and make progress.

O. P.-R.: Fundamental mathematics is one of the least feminised disciplines in French universities. Working with colleagues, we have created ‘May 12th’, an international day in honour of women in mathematics. I also participated in the organisation of internships (‘Les Cigales’) for high school girls to teach them about the research process in mathematics in a friendly, non-mixed atmosphere. And I co-authored the book Matheuses (CNRS Éditions), which explains the mechanisms behind the exclusion of girls and women in the sciences, especially in mathematics. ♦

- 1. Mathematician, CNRS researcher at the Institut Camille Jordan (CNRS / École Centrale de Lyon / Insa Lyon / Université Claude-Bernard Lyon 1 / Université Jean-Monnet Lyon 3).

- 2. Astrophysicist at the CRAL astrophysical research centre (CNRS / ENS de Lyon / Université Claude-Bernard Lyon 1) and president of the Femmes & Sciences association.