You are here

Biodiversity beneath the tarmac

A city is intrinsically an artificial space. No other human creation shows more clearly the impact of our occupation of the planet, with rampant urbanisation being one of the key factors in the rapid erosion of biodiversity. It is true that in mediaeval Europe, urban settlements – although no Noah’s Ark ) – were still largely open to the surrounding countryside. Their dwellers lived in proximity to cattle and their manure, to vineyards, gardens, pastures, and fields. But as time passed, just about everywhere “the ‘city vs. nature’ dichotomy intensified”, explains Philippe Clergeau, professor emeritus at the CESCO.1 “The urban fabric became more and more mineralised and impermeable, especially in the second half of the 20th century with the widespread construction of infrastructures and installations serving the automobile-based lifestyle.”

Without becoming biological deserts (in fact, some urban parks are home to greater biodiversity than certain intensive farming zones!), metropolises have gradually lost all traces of “untamed” nature (e.g. stagnant water, open-air waterways, wet areas, unmanaged ecosystems, etc.), replacing them with controlled, clean, sanitised flora and fauna – in short, more ornamental than functional. Hence the urgency of “making cities more liveable for both humans and non-humans, and redefining what urban socio-ecosystems ought to be,” emphasises Xavier Le Roux, a researcher at the National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and Environment (INRAE) and codirector of the PEPR priority research programme Solu-Biod.2 “We must rethink the city and urbanisation in order to slow the erosion of biodiversity, which is itself crucial for the future of urban areas.”

Plants cannot be just “window dressing”

The more parks, squares, private and community gardens, tree-lined streets, vacant lots, ponds, water run-offs, riverbanks, etc., that a city has alongside individual houses and blocks of flats, the more living species it will accommodate, cohabiting in these natural spaces and providing numerous ecosystem services.

“Far from being mere decorative elements, intended to look pretty and smell nice, plants help combat atmospheric pollutants like nitric oxides, sulphur dioxide, airborne particulates, heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, dioxins, or volatile organic compounds,” reports TETIS3 researcher Christiane Weber.

“In addition to capturing CO₂, trees also provide shade and help protect against wind and noise pollution,” she adds. “And, unlike tarmac and buildings, which absorb sunlight (releasing at night the thermal energy that they store during the day), water and plants, by evaporation or evapotranspiration, raise the atmospheric humidity, a welcome phenomenon in the summer. Furthermore, revegetation helps retain water run-off in the soil, providing water for vegetable gardens, orchards and ornamentals, thus eliminating or at least reducing the need for artificial watering, lightening the load on the drainage systems, and purifying rainwater naturally.”

Roofs are another important consideration. They account for more than 30% of the total surface of the average Western city. The creation of green rooftops brings an additional touch of nature to the city centre – provided that it is a “natural meadow” or “garden” type of environment, and not just a thin mineral substrate covered with a mat of precultivated sedum or similar greenery with no real ecological benefits. As Clergeau points out, “Dense shrubbery should not be left out as it constitutes an even better place for animal species to nest and find food.”

With less concrete, pollution, noise and constant artificial lighting, our cities could also provide a more favourable living space for numerous faunistic communities: birds, bats, pollinating insects, hedgehogs, amphibians, etc. Making a city hospitable to cave-dwelling birds in particular (bluetits, sparrows, starlings…) means integrating nest boxes in the frame, on the façades or on the roof of buildings during construction. And the best way to minimise an edifice’s ecological footprint is to use a maximum of reclaimed (demolition waste, recycled textiles) or bio-based materials (hemp concrete, flax fibre, straw, etc.) , along with more soil-friendly construction methods like building on piles or stilts (levelling, excavating and terracing tend to break down the structure of the soil and destroy its biodiversity).

Let the grass grow wild

But letting nature take its course in the city, in keeping with the dual principle of “providing as much maintenance as necessary but as little as possible” and “favouring local species over exotic plants” (which are often invasive and allergenic), inevitably means violating certain criteria of urban beauty.

Lawns converted into meadows (a major source of seeds and insects for granivorous and insectivorous birds), dead leaves and trees, nettles, wild brambles and weeds in public parks and cemeteries… This kind of unintended greenery can look as though it is simply neglected, to the displeasure of the inhabitants. “More generally, if we want to allow species that have fled the urban environment to find a new place within it, we need to re-examine mankind’s relationship with nature and its cultural underpinnings,” Le Roux notes. “And we have to explain how bolstering a city’s green frame benefits its population’s well-being and psychological health.”

Consequently, living near natural areas where people can enjoy sport activities, take walks with their families, have picnics, form closer ties with other neighbourhood residents, engage in meditation, reconnect with the rhythm of the seasons, etc., reduces the risk of depression, anxiety, stress and respiratory disorders, while improving cognitive capacities (including attention). Not to mention that it improves the lives of the underprivileged, as the public space is their only property.

“Allowing city dwellers to restore links with nature represents a change of paradigm rooted in the political sphere and encompassing the future of a city,” Clergeau emphasises. “This approach is all the more likely to succeed if it is backed by committed elected representatives, persuasive administrative officials, well-qualified partners (architects, urban planners, ecologists, the construction industry…) and properly informed citizens. The latter need to be aware that, to prevent urban sprawl, the foremost solution is urban densification – ‘building a city on top of the city’, as people used to say. This is indeed an important goal, provided that the chosen methods don’t lead to over-densification and neighbourhoods devoid of natural spaces. Prioritising industrial wasteland, disused premises and de-impermeabilisation to compensate for new construction won’t have to compromise on the development of high-quality private and public spaces that improve their inhabitants’ lives. This is the kind of forward thinking that needs to form part of future urban planning.”

Creating mosaics of ecosystems

Another key point: it is not enough for a city to have multiple natural zones if these biodiversity “hot spots” are isolated from one another. Built-up areas, road infrastructures, railways and other installations (wire fences, etc.) are all more or less insuperable obstacles to the unimpeded circulation of animals and plants. Similarly, buried waterways can no longer serve as corridors facilitating the movement of various species.

“This fragmentation causes an imbalance in the lives of certain animal and plant populations,” explains Solène Croci of the LETG.4 “Continuous functional links between the different natural zones are therefore necessary, along with a network of biodiversity reservoirs, in order to create a mosaic of interconnected ecosystems. This will make it easier for the resident species to move about, find food, reproduce, rest, communicate, etc. – in other words, to survive.”

And what if the goal – unlike what more and more local authorities seek to achieve – were not just to create ecosystems within the city, but also, and above all, to “make it a vast self-regulating, self-regenerating social and ecological system, as found in nature”? Clergeau suggests. “The ‘regenerative urban planning’ that we advocate consists in providing built-up areas with ecosystems as close as possible to those found in nature (in particular with many local species and sufficient surface areas), transforming the urbanised space as a whole so that humans are no longer considered the dominant species, but rather one species among many, and connecting the city to its bioregion.”5

Focusing on the small picture

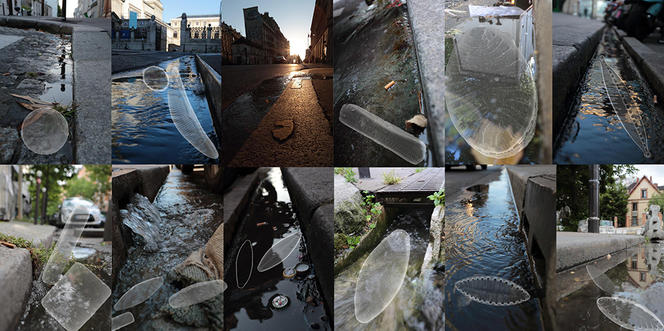

Linking the future of humans with that of urban biodiversity has, at the very least, the merit of focusing attention on smaller species – in fact, much smaller. “Biodiversity in cities is not limited to macroscopic organisms, in other words plants and animals,” notes Pascal-Jean Lopez at the Laboratory of Biology of Aquatic Organisms and Ecosystems (BOREA).6 “There is an invisible biodiversity that is just as important for the functioning of an ecosystem: the diversity of microorganisms.” They can be found bustling about on the walls of buildings, in the soil, in the air, in house dust, and also… in the gutters. “By analysing the microbes present in the gutters of the 20 districts of Paris, in the nonpotable water used to clean the streets and irrigate the parks and gardens, and in that of the Seine and the Canal de l’Ourcq, we discovered the existence of nearly 7,000 different species of eukaryotes,” the researcher reports. “Diatoms (brown microalgae of the stramenopile group) made up around 65% of this rich biodiversity, which also includes fungi, zooflagellates (protists with flagella but devoid of chlorophyll), bacterivores, etc.”

Could the microbes (eukaryotes and bacteria) that populate our streets help reduce urban pollution? The idea is gaining ground. “We would like to show that these microorganisms, beyond their function as ‘markers’ of a city and a society at a given moment, could be involved, even on a small scale, in bioremediation processes – in other words, they could be used in some way to clean the streets,” Lopez suggests. “Rather than dismissing or trying to eliminate this urban compartment, it would be wise to study it more closely, to ‘take better advantage’ of certain microbes’ capacity to break down solid wastes and other types of pollutants.”

Fighting environmental amnesia

One thing is certain: as city dwellers become alienated from biodiversity, they are less aware of the staggering decline of many life forms and thus less inclined to take action for their preservation. “We mostly focus on what constitutes the frame of reference that we have established, primarily in childhood, and which we consider to be the right one,” says Anne-Caroline Prévot of the CESCO.

Yet, between ever-greater urbanisation and our modern-day lifestyles, children are increasingly losing touch with flora and fauna. Along with teenagers, they spend very little time outdoors on a daily basis, “thus foregoing a ‘direct experience with nature’ that schools cannot replace, and without which any theorising is pointless,” Prévot adds. “The decline is such that in 2002, the American psychologist Peter Kahn began referring to it as ‘environmental generational amnesia’. In particular, it triggers a vicious circle: how can people be concerned about the degradation of nature when it is considered less and less important by each successive generation?” Not to mention the fact that most popular cultural products targeting youngsters (cartoons, science-fiction blockbuster films, etc.)7 rarely if ever feature vegetation in outdoor scenes.

More than ever, an effective response must be found to the alterations of biological processes caused by urbanisation, as well as more direct and effective ways to raise awareness among as many city dwellers as possible of the usefulness of biodiversity, and to convince them of its ecological, moral, aesthetic and economic value. “To consider that confusing Victor Hugo with Molière is worse than not being able to tell the difference between a plane tree and a maple, or a blackbird and a starling, somehow means underestimating the impact of the disappearance of nature from our cities, and even from our common cultural background. In point of fact, nature and our relations with it remain a vital aspect of all human life,” Prévot stresses, advocating harmony between humans and non-humans. So the grass is no longer greener outside of cities.

- 1. Centre d’Écologie et des Sciences de la Conservation (CNRS / MNHN / Sorbonne Université).

- 2. Biodiversity and nature-based solutions programme led by the CNRS / INRAE (in collaboration with IFREMER / IRD/ MNHN / Aix-Marseille Université / Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1 / Université Grenoble-Alpes/ Université de Montpellier / Sorbonne Université).

- 3. Laboratoire Territoires, Environnement, Télédétection et Information Spatiale (CNRS / Cirad / AgroParisTech / INRAE).

- 4. Littoral, Environnement, Télédétection, Géomatique (CNRS / Nantes Université / Université de Bretagne Occidentale / Université Rennes 2).

- 5. “Projets urbains régénératifs: de l’idée à la méthode” “Regenerative urban projects: from ideas to methods” (in French), E. Blanco, Ph. Clergeau, Métropolitiques, 20 June, 2022. https://metropolitiques.eu/Projets-urbains-regeneratifs-de-l-idee-a-la-m....

- 6. (CNRS / MNHN / IRD / Sorbonne Université).

- 7. “Science fiction blockbuster movies - A problem or a path to urban greenery?”, Marcus Hedblom, Anne-Caroline Prévot, Axelle Grégoire, Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, Vol. 74, August 2022.

Explore more

Author

Philippe Testard-Vaillant is a journalist. He lives and works in south-eastern France. He has also authored and co-authored several books, including Le Guide du Paris savant (Paris: Belin) and Mon corps, la première merveille du monde (Paris: JC Lattès).