You are here

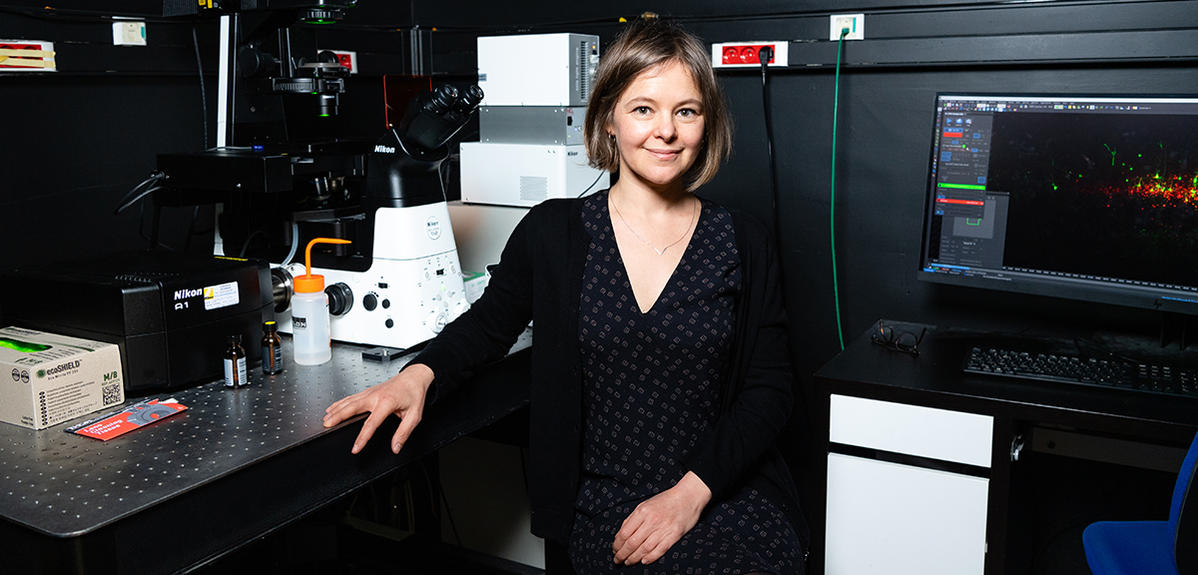

Cécile Charrier, a head full of synapses

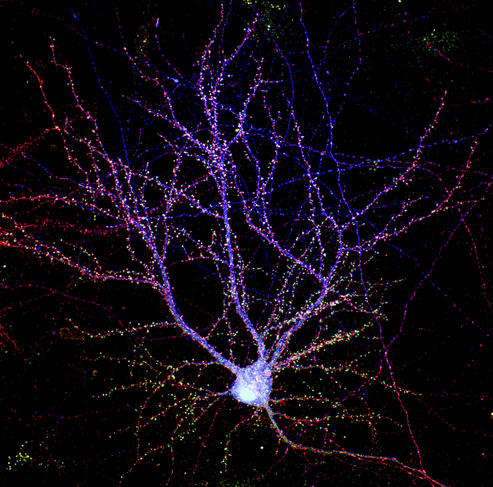

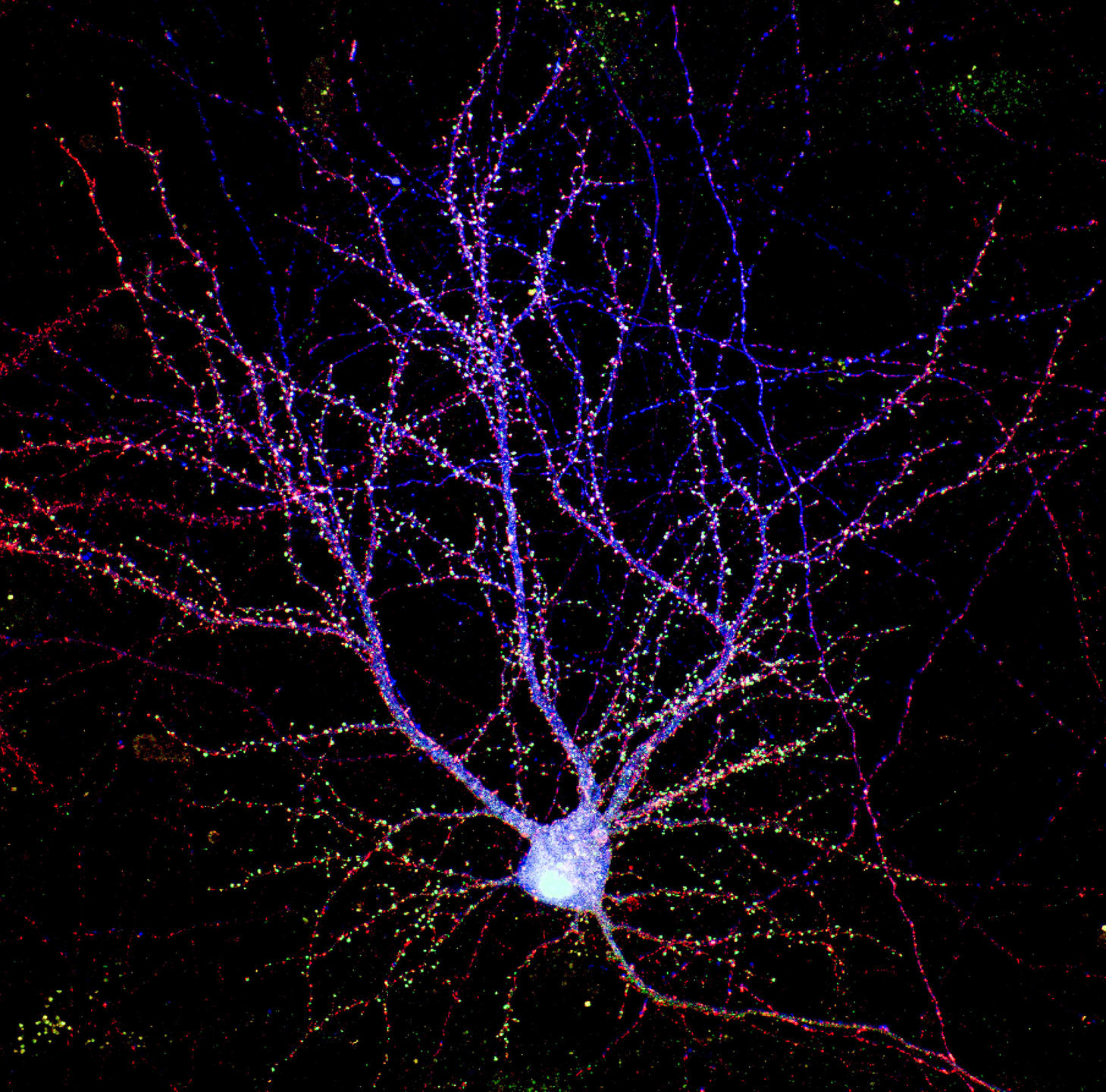

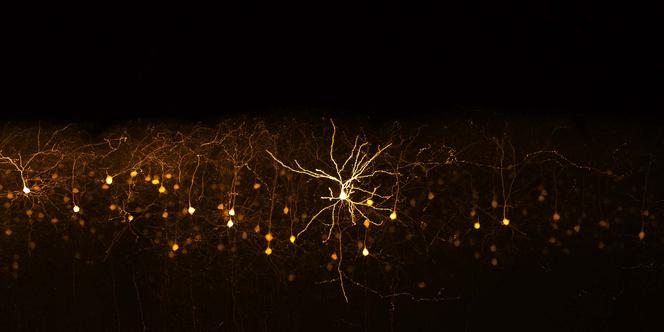

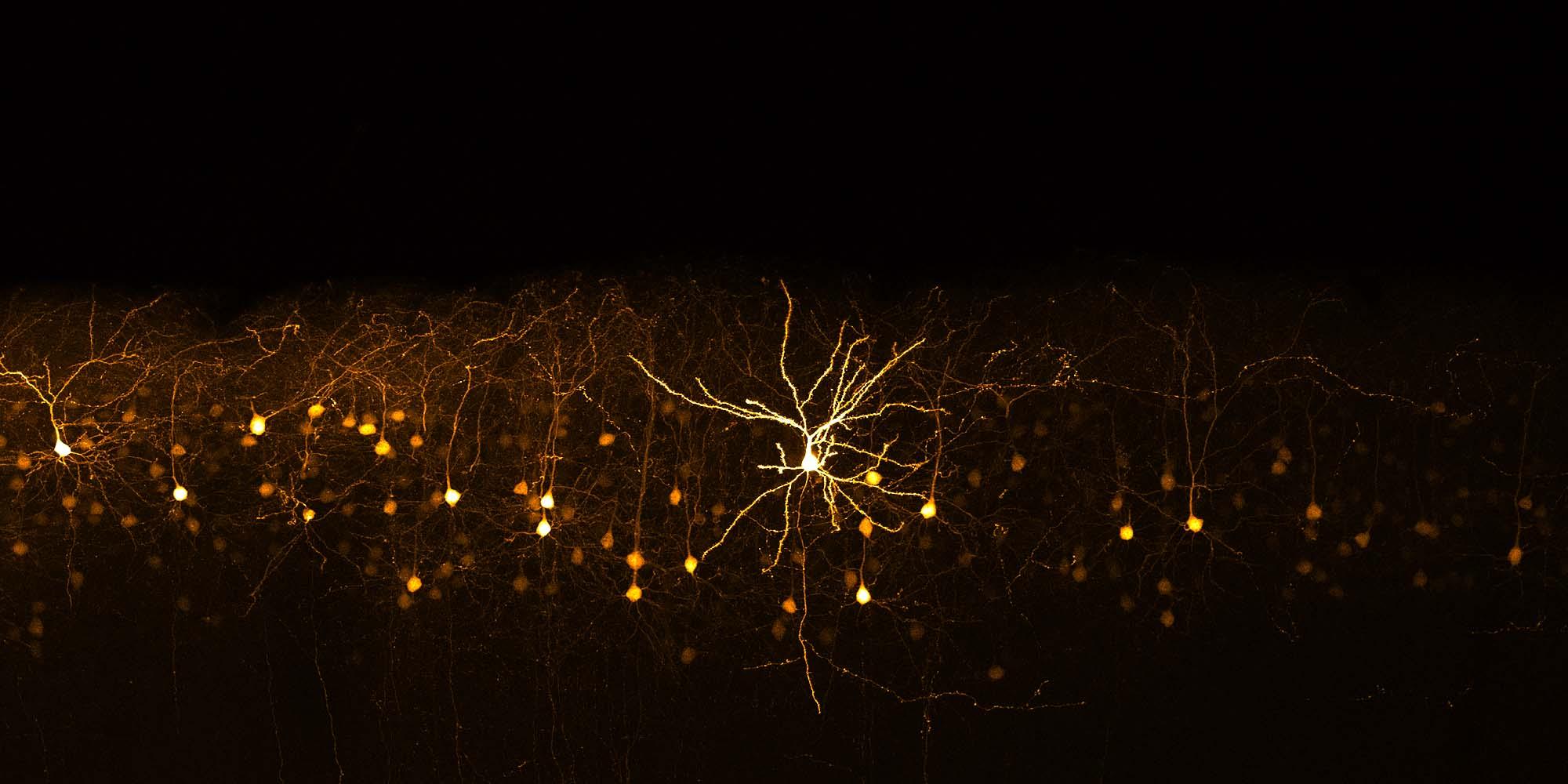

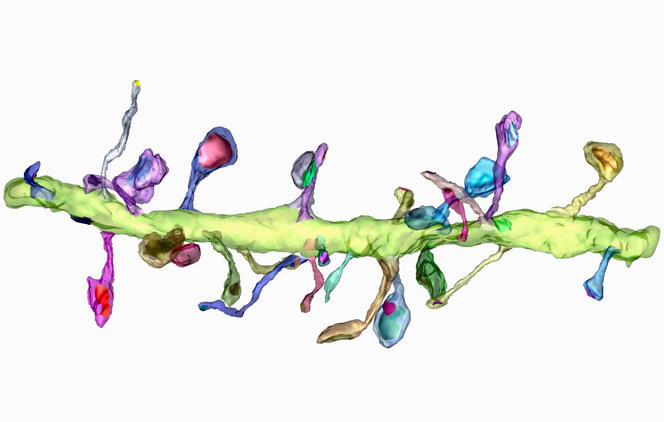

On a shelf in her office at the Biology Department of the Paris-based École Normale Supérieure (IBENS),1 Cécile Charrier has placed a framed magnified image of a neuron. “I think neurons are very beautiful. Before we look at them under the microscope, we label them with fluorescent probes in order to see the synaptic proteins, and the resulting images are always full of bright colours. In my opinion, observing a neuron and its synaptic connections is a bit like looking at people shaking hands,” she enthuses.

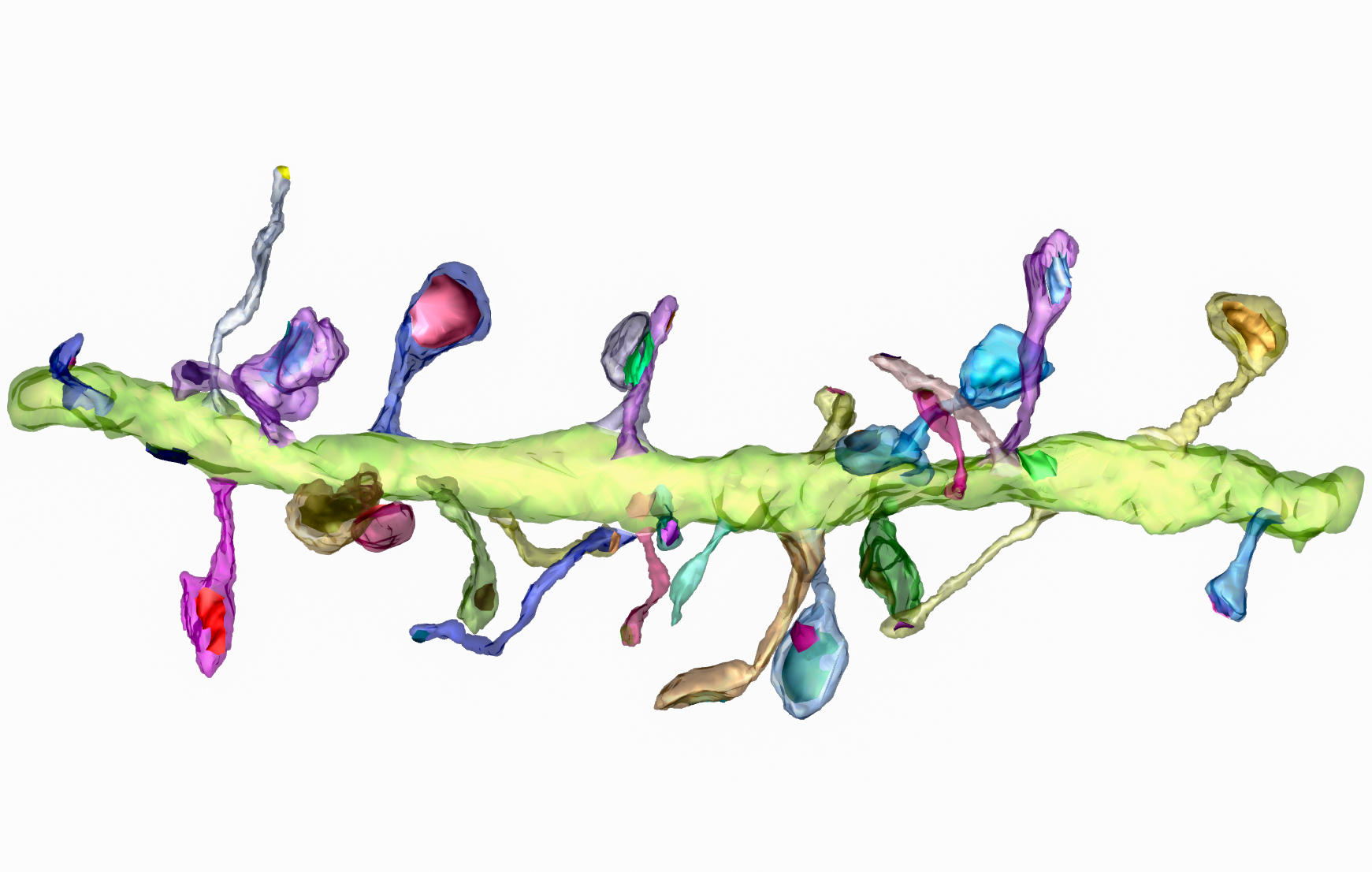

For some 15 years, the young scientist has been observing the connections that ensure the transmission and processing of signals between neurons, without which our nervous system would not be able to function. “Our synapses are responsible for all our emotions and all our behaviours. They control fear, hunger, memory or learning, for example,” she adds. What she is hoping to elucidate is how the functioning of human synapses differs from that of other animals.

“We are trying to understand how certain genetic mutations that occurred during human evolution have affected the fundamental mechanisms underlying the development and plasticity of synapses. Synaptic plasticity is a process that enables the brain to learn and adapt throughout life, and it is particularly important in children and adolescents. In humans, the brain in general – and synapses in particular – develop over periods that are much longer than in other mammals; indeed, it is thought that the human brain only reaches maturity at around 20 years of age. This increases the influence of the environment and social interactions, but also vulnerability to certain neurological or psychiatric disorders such as autism, schizophrenia or learning difficulties,” she explains.

To reward her efforts, last autumn the researcher received the Irène Joliot-Curie Young Female Scientist of the Year prize, a token of appreciation from her supervisory ministry which each year rewards the work of five women from the world of research. The 39 year-old biologist puts her success down to her career choices, but also to luck. “My postdoctoral studies had a major impact. They raised important new questions that I was subsequently able to address when I returned to France,” she explains. After a Master’s degree in biology at the ENS in 2005 and a PhD in 2009, Charrier indeed decided to cross the Atlantic to San Diego (US), where she worked on the SRGAP2C gene that appeared at the time when Australopithecus and Homo separated, around 2.4 million years ago. She managed to show that this gene plays a crucial role on the development of characteristics specific to human synapses, a discovery that determined her subsequent career.

“Antoine Triller, my PhD supervisor, always said that we were ‘not supposed to do things that are easy’. It was his way of explaining that science must not take the easy route; discoveries will only be possible by taking risks and daring to ask questions off the beaten track in order to make progress. His intellectual rigour was an inspiration, and I told myself that I would not necessarily do what others find interesting, but that I’d work on something that interests me instead.”

Of her years in the US, she mostly remembers the atmosphere conducive to innovation that prevailed in her laboratory, and recalls its director, Franck Polleux. “Anything was possible for him. He never put any intellectual or technical barriers on our projects. This reasoning allowed me to unleash my creativity,” she acknowledges. The biologist also realised that scientific interests can differ as a function of cultures. “In California at that time, the focus was on neurons derived from stem cells. It took longer for this subject to be taken up in Europe, particularly because of the ethical issues involved,” she observes.

Charrier returned to France in 2013 and set up a research team in Paris. It initially comprised two people and gradually expanded. Obtaining funds from Europe in 2018 was a significant boost, as a result of which the scientist and her team were able to pursue their research on the role of genes related to human evolution in the regulation of molecular and cellular mechanisms in neurons.

The young laureate now leads a team of eight. Her everyday activities are organised around the supervision of students and postdoctoral fellows, discussions on scientific topics, applications for funding, the dissemination of research results through publications or conferences, the production of reports and assessments, and reading publications by other scientists throughout the world. She has extended her research to other human genes in order to better understand their effects on synaptic activity. Which leaves her little time for observing neurons under the microscope. “I miss my lab bench sometimes; I’d gladly exchange it for my emails! As a biologist, you need to take the time to look at samples. This is what sometimes enables us to reformulate a hypothesis or explore a new area of research,” she insists.

She is now doing the job she had been dreaming of as a child. “I’ve always found the brain fascinating, and I knew from high school that I wanted to become a neurobiologist,” she explains. In the future, her career may inspire other young girls who wish to work in biology. “I was very lucky to follow a straightforward professional path and land a job when I was quite young. The average age at recruitment has risen a great deal. This poses particular problems for women since they sometimes need to choose between their personal and professional lives. We need more initiatives to enable them to continue working in academic research.” Beyond her passion for science, Charrier is a woman of conviction.

- 1. CNRS/ Inserm/ ENS.